What kept teachers motivated over the last 18 months? How did they cope with the pandemic, not being able to go to school, and the sudden need for online and blended learning and teaching? What strategies did teachers use to cope with the unexpected? And, most importantly, what do these strategies and practices tell us about supporting teachers better in the future?

At STiR Education we work with government school officials and teachers across the states of Delhi, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, and these questions were on our mind as we supported their response to the pandemic. Our approach includes creating peer networks of officials and teachers, giving teachers the autonomy to decide classroom strategies, providing feedback through peer observation, and enabling reflection. When schools were removed from the equation during the COVID-19 pandemic, we struggled to see how we could do this digitally. With no classroom practice, what would teachers reflect on? And what would officials and peers provide feedback on?

While this was a tall order, teachers rose to the challenge. They came up with teaching and learning strategies that they feel has added value and enriched them as educators. We were also pleasantly surprised with the resilience and willingness of district- and block-level officials and teachers to find new ways to support student learning.

Now that they are back in school, teachers shared that they would like some of these practices to continue. Here are six steps that governments and policymakers can take to support teachers and build a stronger teacher community as schools reopen:

1. Increase teacher autonomy

For the longest time, teachers in India have been limited by an overloaded curriculum, fixed textbooks, and in-service teacher training modules that follow a one-size-fits-all approach. Though not without its challenges, the pandemic gave teachers the autonomy to reach students in many different ways. Teachers came up with multiple content formats, which included booklets, worksheets, small videos, and audio recordings that could be sent through WhatsApp and did not require a textbook and face-to-face teaching. Once the lockdown was lifted, teachers started community visits and distributed material to children they could reach. Where children had access to phone and internet, teachers conducted online classes.

For one of our activities built around encouraging students to reflect and share their feelings, we saw teachers contextualise this to students’ needs. Some students drew, some wrote in notebooks, some recorded audio, and some typed out their diaries. As one teacher put it, “We were not forced to follow any one strategy and hence we innovated based on local needs. It was challenging and time-consuming. But students responded positively and this motivated us to find better ways.”

Though teachers found creative ways to teach, they often improvised without a lot of planning. With schools reopening, giving teachers more say in curriculum design, planning timetables and the method of teaching will go a long way in improving teacher motivation as well as performance. The pandemic has shown us that teachers with more experience put greater effort into reaching students. Governments can take advantage of their rich experience and commitment by giving teachers more control over the teaching and learning process.

2. Give teachers agency to direct their own learning

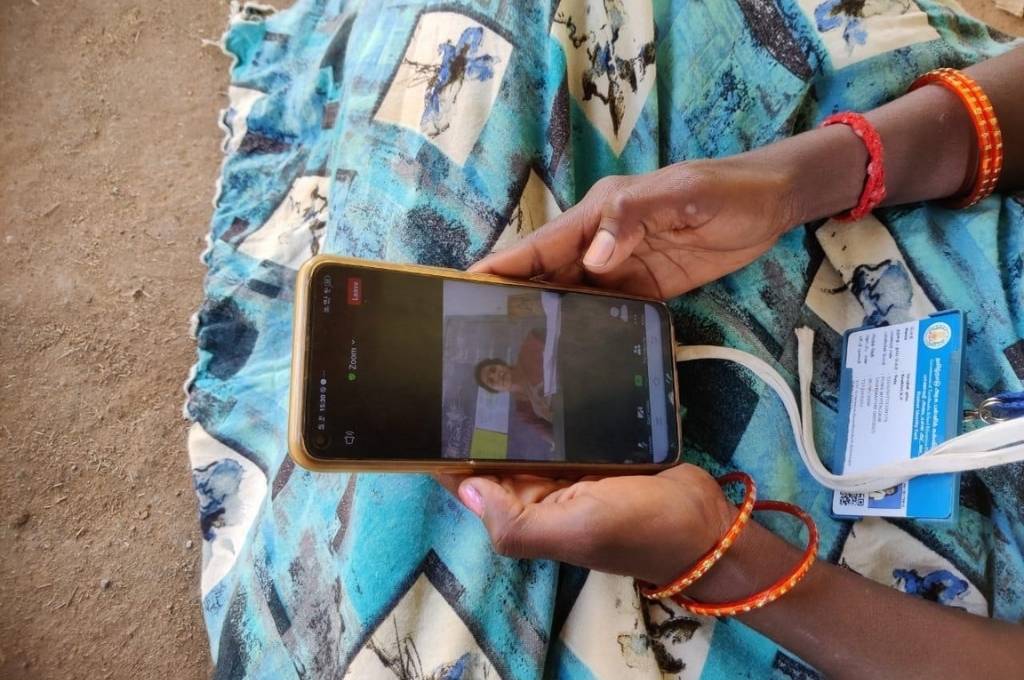

During COVID-19 teachers had to quickly adapt lesson content planned for physical classes to an online or a remote format. Doing this successfully requires a different set of skills, and so teachers had to brush up their technology skills and learn virtual tools. While not mandated to do so, many teachers in our network responded positively to our inputs on digital skills and learning virtual tools. They proactively asked for help and practised strategies for making learning accessible with their peers and students. Whether it was learning to join a link for an online meeting, taking online classes, recording videos and audios, or using forms, teachers took ownership of their own learning.

Teachers have a good understanding of their developmental needs and the gaps in their skill set. Instead of centrally planned one-way training modules, states and the education ministry can create a bouquet of courses for teachers to choose from. It will also benefit our policymakers to ask teachers what support they want and challenge teachers with innovative content.

3. Create communities of practice

Giving teachers agency over their own learning and autonomy to innovate is not enough if teachers do not have a supportive peer and official network. One of STiR’s key areas of work is to help set up teacher networks within schools and clusters so that teachers can discuss strategies, get feedback from their peers, and reflect on their practices. They can share their learnings and experiences in a non-threatening environment. This support system became especially important at a time when teachers were struggling to reach students. Many teachers shared how they found the fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 emotionally challenging. They also discussed coping strategies and gave suggestions and support to each other.

These communities of practice were also open to block and district officials, who looked to their peers to understand what was happening in different districts, shared challenges, and discussed best practices. States can play an active role in creating structured communities of practice at the school and district level. Carving out space in the daily school timetable for this will increase peer collaboration and provide academic, social, and emotional support to teachers and officials.

4. Strengthen the skills and infrastructure for blended learning

During the pandemic, teachers realised that technology can support everyday teaching practice in multiple ways. They found that small audio and video modules can be created and sent to students as additional material after class. Some teachers also recorded personalised voice notes for parents. This encouraged parents to sit with their children, complete the activities, and send videos back to teachers.

In order to intentionally use digital teaching and learning tools, teachers need time, training, and tools.

Blended learning gave both teachers and students a degree of flexibility for teaching and learning, since neither was restricted to the classroom. For instance, one teacher made several small video modules for a topic and sent it to students over the course of a month. “Since I was not bound by a timetable of 45 minutes, I took the liberty to experiment with different content on the topic. But I would like to get some formal training on how to do this better,” she shared. Technology can also take a lot of administrative burden off teachers. “We did most monitoring meetings online and that saved a lot of travel time,” added another teacher. We found that teachers are keen to continue with blended teaching strategies in school. One teacher adds, “Technology can support my teaching if I plan it better and have better resources. This momentum should not be lost now that school has opened.”

In order to intentionally use digital teaching and learning tools, teachers need time, training, and tools. With adequate technological infrastructure and teacher capacity building, schools can create a system of sending homework reminders to parents through WhatsApp, design modules and tests, and involve parents in their child’s education. Unfortunately, while senior secondary and secondary schools across many states have desktops and laptops, the active use of technology has not been a part of teachers’ daily work. In many cases, computers are dysfunctional and access to regular internet is a challenge. For blended learning to succeed, governments need to provide access to functional technology, integrate technology into everyday teaching, and build teacher capacity around blended pedagogies.

5. Fill teacher vacancies to enable differentiated teaching

During the pandemic teachers became flexible and changed their teaching strategies to fit the needs of their students. For example, many students had access to a phone only in the evenings and we saw teachers in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu organise classes in the evenings. Some students had basic phones and so teachers recorded lessons and homework for them. They called students to check on individual progress. Children who struggled were given one-on-one time. “I realised that the weaker students were responding well to this individual attention and I tried hard to design some meaningful lessons for them. But once school is back in full swing, I will not have the time to give individual attention. My class size is huge and there are other administrative duties. I would love to have a small class size and time to try some creative strategies,” a teacher said.

By hiring more teachers and improving the student-teacher ratio, the government can encourage such activities without additional burden on the teachers. This will ensure that students, especially the weaker and marginalised ones, benefit from more attention. It also has the potential to improve both teacher and student motivation, while enhancing learning outcomes.

6. Prioritise the social and emotional health of teachers

The pandemic has put the spotlight on teachers’ social and emotional health worldwide. Our sessions on the social and emotional well-being of teachers were attended by nearly 2.5 times more teachers than before. Teachers admitted to connecting over and reflecting on their feelings for the first time in a structured manner. Since many teachers ended up going to communities and visiting students’ homes, it also gave them an opportunity to understand student backgrounds better.

Delhi has been a front runner, having introduced the Happiness Curriculum across its schools much before the pandemic. Through this, teachers were introduced to concepts of mindfulness, deep listening, and social and emotional well-being. But it was only during COVID-19 that these concepts took root and became central to teacher network meetings, where teachers discussed and practised the concepts. Other states can follow suit by introducing counselling and mindfulness practices as a regular feature for teachers. This can be a platform for teachers to discuss not only their well-being but also strategies for the social and emotional well-being of their students.

The COVID-19 pandemic has kept children and teachers out of school for almost two academic sessions now. Teachers have struggled to adapt to the change, but also gained a lot—they were resilient, overcame their fear of technology, learnt new tools, innovated widely, connected and collaborated with peers, and made time for professional development. Our education system needs to capitalise on these gains and support teachers to make these gains sustainable. Bringing children back to school, closing the learning gap, and ensuring their social and emotional well-being is a tall order for the system, and especially for teachers. Creating an enabling environment will go a long way in making this happen.

—

Know more

- Learn more about why teacher agency matters and what we can do to improve it.

- Read the UNESCO State of Education Report for India 2021, which discusses the impact of the pandemic on India’s teachers and how they can be supported