READ THIS ARTICLE IN

Areca nut farming in Karnataka: Is groundwater a small price to pay?

Groundwater levels are in steep decline in the semi-arid parts of peninsular India. Despite numerous studies and hundreds of crores of investment in recharge schemes, the situation seems to only get worse.

Preliminary research shows that a switch from traditional crops to commercial species, fuelled by the borewell revolution, is partly to blame. But why are farmers continuing to drill deeper, risking every penny of their savings, chasing a source of water that could fail at any time?

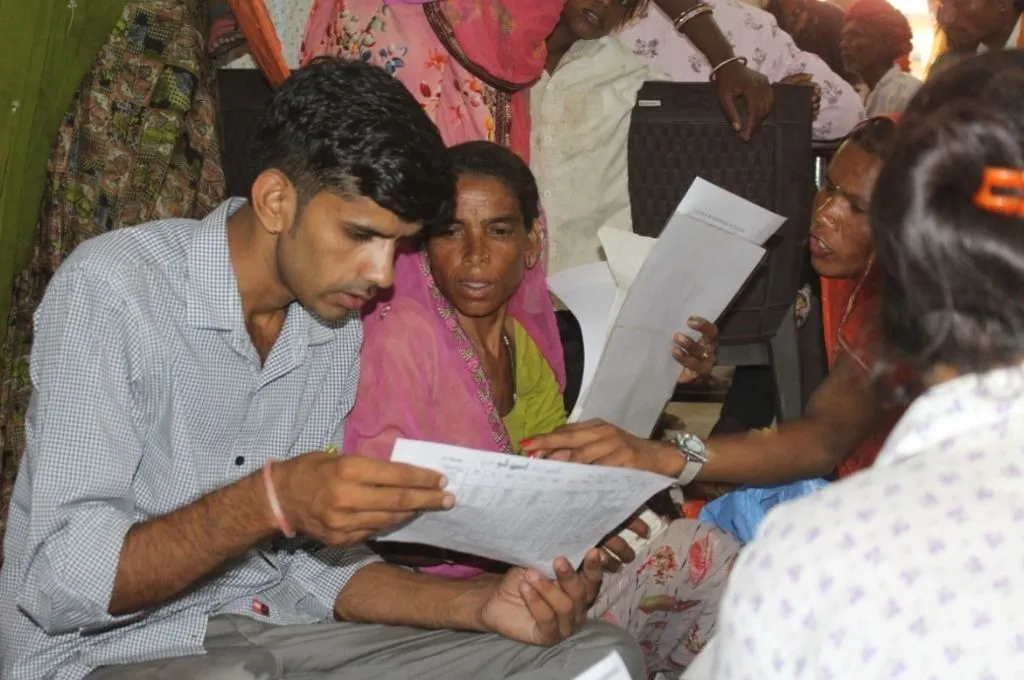

In search of answers, we went to Chikkahejjaji in the Bengaluru Rural district of Karnataka. As groundwater levels deplete and a crisis of water scarcity spreads in agrarian belts, we wanted to understand how areca nut, a water-intensive crop, became one of the most important cash crops in the state.

A typical areca nut plantation has about 400 trees per acre, and each tree (in semi-arid regions) needs 15 litres of irrigation every day for about six months of the year. This translates to approximately 350 mm/year of irrigation demand, in a place where groundwater recharge probably has an upper limit of 50 mm/year.

However, juxtaposed with areca’s high water requirement is its financial lure—the crop fetches an average of INR 4,50,000/acre/year compared to the paltry INR 60,000/acre/year for groundnut. As Raju, a farmer near Doddaballapur, put it, “If the borewell fails we lose 1.5 lakhs, but if it succeeds, we earn 4.5 lakhs in the same year.”

But how big is the demand for the crop?

Our research showed that while areca started out as a traditional crop selling at INR 700–800 per quintal in the 1970s, it experienced a surge in the 1990s due to the expansion of the gutka industry. Prices have steadily climbed since, and it sells today at up to a lakh per quintal.

Over time it has become one of the key cash crops of Karnataka, and village after village in semi-arid and arid regions are digging increasingly deep borewells to cash in on this water-guzzling money-spinner. In fact, more than 800 of the 900 households in the Chikkahejjaji village are engaged in areca nut processing.

Needless to say, we found that the areca nut market is not a bubble, rather a thriving industry driven by the steady demand created by the gutka industry and supported by a strong network of farmers, processors, and traders.

At a time of worsening water scarcity, it is critical to closely monitor the impact of crops like areca nut and look into what can be done to challenge the dominance that they enjoy in the market. It’s important to note that this is not a ‘free market’; the groundwater boom is driven by the policy of free electricity to farmers. The question is how to direct the state subsidy to help farmers make more sustainable crop choices.

Tanvi Agrawal is a PhD candidate at Wageningen University, Netherlands. This is an edited excerpt of an article that was originally published on The News Minute. To learn more about areca nut harvesting, check out this infographic.

—

Know more: Understand why there’s a need for community participation to address groundwater woes.

Do more: Connect with the author at tanviagrawal2009@gmail.com to understand more about and support her work.