As e-PDS fails in Adivasi areas, families turn to WhatsApp and wall notices

It took Vasantha* and her husband more than eight months to receive food grains through the public distribution system (PDS). They are among thousands of Adivasi families in Alluri Sitarama Raju district, Andhra Pradesh, where ration distribution is still largely conducted offline. Due to lack of internet connectivity, households often cannot access information about the status of their ration card (or rice card); the full quantity of foodgrains they are entitled to; or any changes in the process of ration delivery.

Where PDS is online, food grains are distributed based on biometric authentication. In an offline system, fair price shop (FPS) dealers give 12 physical coupons—one for each month—to ration cardholders. If the family size changes during this time or the government makes any updates to the ration card and if these are not reflected in the coupons, a household ends up being denied their full share of food.

Moreover, if families try to update their ration card details—be it adding new members, splitting the card when newly-weds move into a different house and form an independent household, or making any corrections—they are unable to digitally track the status of their application.

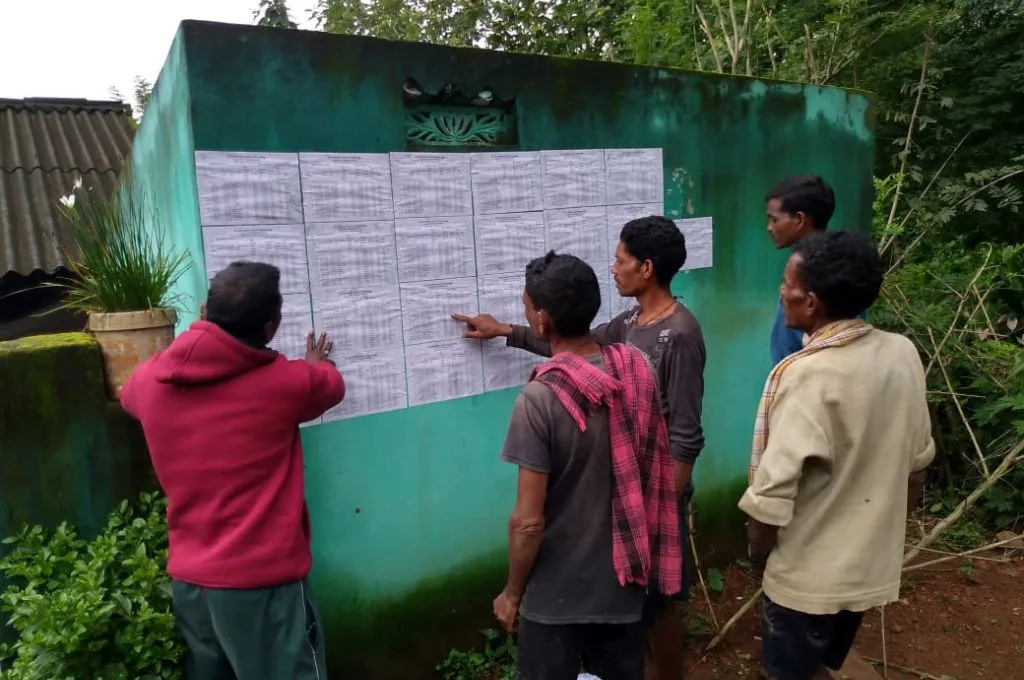

To solve this problem, the S R Sankaran Adivasi Sahaya Kendram—a community-run centre offering details on public services—collects data related to food-grain prices, ration cards, and entitlements of approximately 2,500 households in the area every month. We gather information from different online registries and helplines, translate it into Telugu, and turn it into easy-to-read formats and tables. We share these through WhatsApp messages and as printed notices displayed in anganwadis, panchayat bhawans, schools, and other public spaces across the district. People are able to directly use this information to demand their entitlements.

While Vasantha’s application had been approved online by June 2023, she only learned about it two months later, after finding her details in a WhatsApp message we had circulated.

Since we started sharing data from the key registers—a detailed record of the number of ration cards and units of food allotted every month—many families have been able to get their complete share of ration. This led to tensions initially and the FPS dealers, who were also from the local community, would fight with us and question the accuracy of our data.

Whenever we circulate any information now, we make sure to mention the sources such as the government website or department from where we got the data, so people know that it is verified.

But accessing necessities should not be an uphill battle. The ration card is not a static document; it evolves as families change. However, when these updates are made on digital platforms that are out of reach, households are left at the discretion of FPS dealers.

Online systems are often presented as a techno-fix for corruption or leakages, but they can end up excluding people entirely or make it difficult to access entitlements. Instead, our experience shows that building people-centric offline systems side by side, with timely availability of information, can ensure accountability and transparency while upholding basic rights.

*Name changed to maintain confidentiality.

Pangi Ramanababu and Korra Laxmanarao contributed to this article.

Vanthala Bhaskar and Jartha Matyakondababu are associated with the S R Sankaran Adivasi Sahaya Kendram. LibTech India is a resource partner for the S R Sankaran Adivasi Sahaya Kendram.

—

Know more: Learn how not having a ration card deprives families in Bihar of not just food, but also other essential rights and services.

Do more: Connect with the authors at srsankaraninfocenter@gmail.com to learn more about and support their work.