India is home to one of the youngest populations in the world, with close to 140 million people falling in the 18–23 age bracket. India has more than 50 percent of its population below the age of 25 years and in 2020, the average age of an Indian will be 29 as compared to 48 for Japan. In the last decade or so, psychological research has coined this phase in young people’s lives – emerging adulthood. It is neither adolescence nor young adulthood, but empirically distinct. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future has been decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course.”

In India, these emerging adults make up our promised demographic dividend. However, we know from research that most of them struggle to transition successfully into adulthood – few complete high school, the quality of education is often poor, and many lack livelihood skills and employment opportunities.

I have seen this firsthand over the past ten years, traveling across Maharashtra to meet young people in my capacity as the programme lead of NIRMAN, an educational programme to nurture younger leadership for social change. Often, students, even those pursuing professional degrees like an MBBS, don’t have the confidence or conviction to use their skills in the real world.

In India, the emerging adults make up our promised demographic dividend but, we know from research, that most of them struggle to transition successfully into adulthood. | Picture courtesy: Saahil Kejriwal

I have found that conventional higher education gives a lot of information, and occasionally imparts skills; but one thing that is almost never accomplished is giving students a sense of purpose. We have trained computer engineers, theoretical physicists, and doctors, but whom do they use their skills and information for? Why should they do what they are conventionally supposed to do?

Conventional higher education gives a lot of information, and occasionally imparts skills; but one thing that is almost never accomplished is giving students a sense of purpose.

Within these disciplines, students tend to be exposed to specific examples as templates for the career path they should follow. For instance, as a computer engineer, I must take ‘the’ job, which is at Google or Apple. While this is useful for people seeking such jobs, there is no recourse or space to explore, for those that are not.

Worse still, is that India does not have any theory or framework around the healthy growth of this group. When we talk about young people’s issues, our conversations centre around suicide, road traffic accidents, alcohol and drug abuse, and sexual assault. These may be areas in which young people need help. But we rarely speak about the factors that lead to their positive, adaptive development, for example, having a sense of competence and confidence, values and character, connection, and caring for others.

Lessons from NIRMAN

It is “a stable and generalised intention to accomplish something that is at once personally meaningful and at the same time leads to productive engagement with some aspect of the world beyond the self.”

Related article: Social sector fellowships – Why they matter

The scientific literature states that people generally have four broad types of purposes:

- Pro-social

- Financial

- Artistic

- Personal recognition

At NIRMAN, we focus on the first type; in particular, Vinoba Bhave’s interpretation of the Gita, which talks of purpose as ‘swadharm’. What is the purpose of my being here? To fulfill my swadharm. And what is swadharm? It’s my duty towards others. By fulfilling my duty towards the society that I call my own, I attain my purpose.

It is this concept of pro-social purpose that we share with NIRMAN participants, and try to facilitate their journey towards it. What if one’s focus is not just ‘what will happen for me’, but ‘what can I give?’ For example, one of our participants—let us call him Gaurav—came to me, confused. He is graduating with a medical degree from a top medical college, and is supposed to complete a one-year Medical Officership (MO) bond service in rural India. Many of his peers will opt out.

Gaurav had three questions; first, should he serve the bond or not, or should he spend that time preparing for his post-graduate exam, like his peers? Second, if he has to serve the one-year bond, should he do it in the medical college’s hospital in a big city, because doing so will give him more clinical skills? (Acquiring real-world skills is a big draw for medical graduates.) Finally, should he serve out his bond at a primary healthcare center (PHC)?

Focusing on ‘what can I receive,’ is a big part of how we are groomed in college. But what if we asked, ‘what can I give?’ In Gaurav’s case, he could ask himself: “What happens with me this year?” Or, he could ask: “What happens to the health of the 40,000 people who are the target population of the PHC I might work at?” What should the deciding criteria for my next move be? One, or 40,000? Reflecting in this manner led Gaurav to the decision to serve his one-year bond at a PHC.

Emerging adulthood is a time when people are questioning their identity. It is not uncommon in this age group, to ask, “who am I?” However, our experience with NIRMAN has shown that figuring out and committing to a purpose first—what can I offer—is not only more expansive an exercise, but is also a more effective path to seeking answers to identity questions.

There is little discussion about the larger questions of life, including values and morals; these are ignored as events and exams dominate.

For example, if I were a journalist, my parameters of success would be different than if I were a computer engineer. Based on the boundaries I draw for myself, I might compare my progress with specific benchmarks. Instead of endlessly reflecting on who we are and what our passion is, research advocates that we do what we’re good at and what helps other people. We must identify the social issue that we believe is important and that appeals to us, and in so doing we should reflect upon what it is that we can do to solve that issue. Through this, we can find our purpose, and then, our identity emerges automatically out of this exercise.

Related article: An evidence-based guide to empowering adolescents

This of course is at a conceptual level. Building up to it is a function of self-reflection, a supportive community, mentorship, and time.

Committing to a purpose that resonates with us and also directly aligns with our strengths while solving a social problem, can be a lengthy and internal process. But it must manifest externally as well, so there is guidance for and confidence in the choices we make. To enable this, creating a safe, judgement-free environment is crucial. Not least because the atmosphere across Indian college campuses today can be quite brutal, where displays of vulnerability are subject to ridicule and shaming. But also because there is little discussion about the larger questions of life, including values and morals; these are ignored as events and exams dominate.

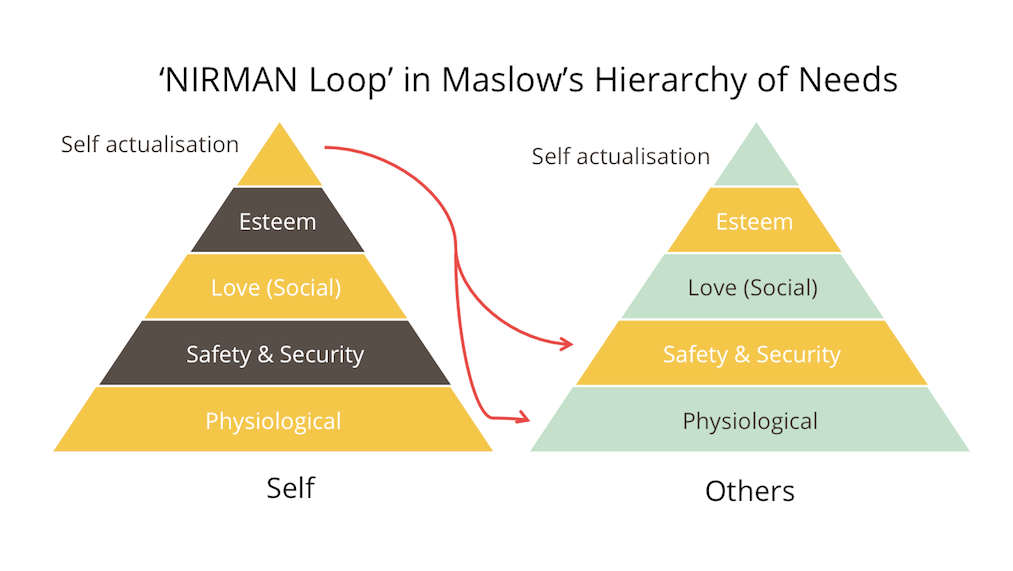

We have learned that the self-actualisation of our participants cannot take place in isolation or in the narrow confines of a secure lifestyle. As shown in the figure below, the ‘NIRMAN Loop’ consists of fulfilling one’s self-actualisation by connecting with others in society who are still at the first two levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

And so by focusing on the growth of young participants; their social contribution to a challenge they wish to solve; and by developing the possibilities of a new youth culture where young people can exhibit courage, can stand for what they think is right (instead of what’s convenient or fashionable), and can focus on finding their long term purpose, NIRMAN builds a 50 year relationship. Today, 40 percent of participants start working full-time on social issues after graduating from NIRMAN. We have also had graduates that haven’t been ready to commit to a social purpose right away, and have instead chosen to work in the private sector. Yet, the community and mentorship support throughout their careers continues to help them keep a connection with the work.

Further reading: Adolescent Psychology in Today’s World: Global Perspectives on Risk, Relationships, and Development by Michael J. Nakkula, Andrew J. Schneider-Munoz