Many of us working in the field of nature and wildlife conservation began our vocational journeys because of our love for and connection with animals, nature, and the wilderness. Research shows that people who have a deep emotional and physical bonds with nature are more likely to understand it, and, in turn, feel compelled to conserve it. Children and young adults who have had meaningful nature-based experiences early in life often carry this connection into adulthood.

The evidence is clear: environmental and nature education should start early. But how can children and adults experience nature in ways that are meaningful and can can seed a lifelong affinity with the natural world?

In 2003, the Supreme Court of India issued an order to introduce Environmental Studies or Environmental Sciences (EVS) as a compulsory subject in Indian schools. The intention was to build awareness of environmental issues among students and, in doing so, set them onto a path of conservation. The Court held that environmental education was a prerequisite to fulfilling a citizen’s constitutional duty to protect and improve the natural environment.

Building on this vision, Nature Classrooms was established in 2018 to work with educators on developing culturally relevant and locally grounded approaches to nature learning. Drawing from the work and ideas of several organisations and initiatives already engaged in this space, the programme identified key gaps and opportunities in nature education by working with schools and educational organisations across diverse ecological and social landscapes. This included cities and peri-urban towns in Karnataka, Kashmir, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu.

Through research on nature learning, curriculum reviews, and through direct long-term engagement with grassroots organisations and educational institutions, we have seen first-hand how EVS, as a compulsory subject, has immense potential to build ecologically connected and aware citizens. However, these well-intentioned efforts have had to contend with the rigidity and conformity of India’s education system.

Why EVS misses the mark

Developing not just care and empathy, but also wonder and curiosity about the natural world can be key to building pro-environmental behaviour. However, much of the way EVS curriculum is currently designed, taught, and perceived often feels mundane, irrelevant, and disengaging for both students and teachers.

There are several reasons for this:

a. Lack of trained teachers and locally relevant learning resources

Over the years, we have found that most students and teachers view EVS as yet another compulsory subject—something they are forced to study rather than experience, explore, and connect with through local geographies and ecologies. Teachers often also tell us that they are expected to teach EVS classes despite having inadequate training in the subject, which frequently falls outside their core responsibilities. They juggle these classes alongside their primary roles as librarians, sports teachers, art instructors, or substitute teachers.

EVS class is often regarded and treated as a “free/open period”.

Moreover, teacher training institutes typically dedicate only a few hours to EVS modules, leaving educators ill-equipped to meaningfully engage with students and to inculcate a sense of excitement and wonder about the subject. The problem becomes more pronounced in high school, where EVS is no longer taught as a standalone subject. Instead, environmental concepts are expected to be woven into the curricula of other subjects. Lacking guidance on how to do this, teachers often forgo this requirement altogether, relying solely on limited content and concepts in textbooks and external tools like YouTube videos, or one-off guest lectures.

It’s no surprise then, that EVS class is often regarded and treated as a “free/open period” where students are allowed extra time to study more mainstream subjects and is often dismissed as an occasional indulgence in the school system.

b. Ill-defined and fragmented subject content

The EVS curriculum does not exclusively focus on the immediate natural environment, local ecologies, or cultural contexts. Instead, it incorporates themes and concepts from the social sciences in ways that feel disconnected from the natural sciences. For instance, a chapter in the Standard II Karnataka EVS textbook focuses on human cleanliness and personal hygiene, while the Standard III textbook includes a chapter on festivals, where children visit a fair and interact with vendors. The next chapter then abruptly shifts to plants.

Not only are some lessons disconnected from nature and our relationship to it, they also lack thematic continuity, making it harder for students to build a coherent understanding of their local environment and our relationships to it.

c. Predominantly human-centric lens

The overall approach of EVS content leans towards a human-centric rather than a nature-centric focus. This is evident in school textbooks across classes. Nature is primarily framed as a provider of services to humans, with an emphasis on the ways in which we can, and should, utilise these ecosystems. By extension, it is this utility value which becomes the foremost reason to nurture, protect, and conserve nature.

Even when textbooks discuss water bodies or water-based ecosystems and caution against pollution and waste, there is no mention of how aquatic organisms such as frogs, fish, birds and plants need and use water, and how it serves as a crucial habitat for them. Textbook chapters, their content, and the overall approach therefore fail to cultivate a holistic, multifaceted, and ecological view of the world we inhabit.

This utilitarian perspective privileges human needs over all other forms of life in various habitats and ecosystems, thereby taking away a learning opportunity from children to be introduced to, and being in awe of, the diversity of life forms that inhabit this world with us.

How young students view nature

To bridge the gap between curriculum and conservation, EVS in India needs a fundamental shift—from textbook-based, human-centric learning to experiential, place-based, and inquiry-driven learning that reflects students’ and teachers’ lived experiences and their specific social and ecological contexts.

To this end, in one of our research projects in 2021–22, we collaborated with Azim Premji University to document and understand how middle school students in Bengaluru and its peri-urban areas related to their natural surroundings, and whether relationships were informed by the EVS curriculum they were taught in their primary school years.

The study surfaced compelling insights, showing us that:

1. Children perceive nature in diverse and personal ways: For some, nature was embodied in the interactions with their pet or a favourite street dog. For others, nature took the form of the tree near their home—one they spoke to when feeling lonely or sad. To some, nature was an unkempt, untidy, and “dirty” area they stayed away from out of fear, or because it was believed to be occupied by mythical creatures.

2. Cities are seen as nature-less spaces: The research also threw light on the stark difference between how children in urban and rural areas perceive nature. For many children of migrant workers, nature seemed to exist only back in their hometowns, in their own ”oorus”, and not in the cities to which their families migrated for work. Not only was the city bereft of nature, but even its mud and soil were considered dirty and unsuitable for play—as instructed by their parents.

3. Nature is imagined as distant and exotic: Young students, especially in cities, often struggled to accept that wild nature exists in and around their homes and schools. Instead, it only existed as something far away, located in forests, or even outside India altogether, in places like Australia and South America seen in nature documentaries. As a result, children often misidentified native species: hornbills found in Indian forests were frequently mistaken for toucans from South America, possibly because of their similar beak shapes.

Insights such as these revealed critical gaps in our approach to EVS. It also helped us understand how to develop relevant resources and pedagogies for teachers and students across different socioeconomic contexts. We were also able to provide guidance for educator training programmes on how to customise resources and methodologies to better align with children’s socio-economic contexts, including their access to, and perception of, the outdoors.

Rethinking nature learning

Until children and teachers are given space to develop a sense of wonder and curiosity for the life forms around them, nature learning or environmental studies will continue to fall short of their intent. We believe that nature education can and should be urgently reframed to foster a deeper, more meaningful connection between students and the natural world they inhabit.

We see this reframing as resting on four core shifts.

1. As immediate and accessible

Students do not need to be taken to forests or city parks to experience nature. Nature education can begin by drawing attention to the diverse natural life already present around them: scraggly shrubs, creepers and wild grasses growing on school grounds, silverfish tucked between book pages, potted plants on balconies, and even the mould on stale bread.

It is equally critical to build the capacity of all teachers, irrespective of their disciplinary training and experience, to feel confident to engage with EVS.

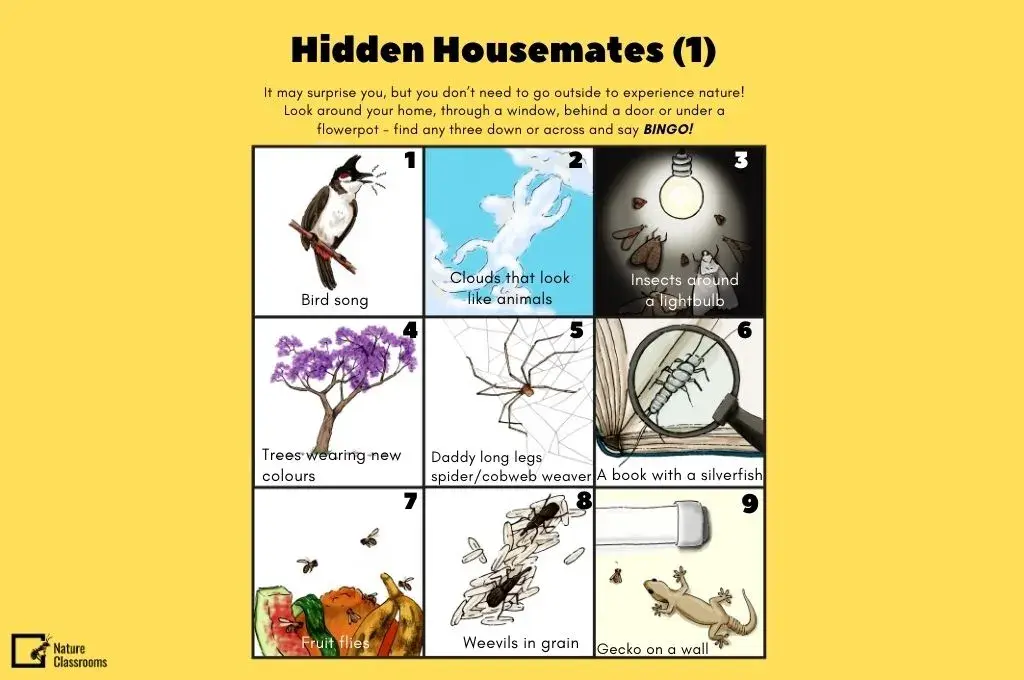

At Nature Classrooms we have been designing and testing culturally relevant and age-appropriate resources that are familiar and easy-to-use. For example, we have designed a series of “Nature and Seasonal Bingos” to encourage people to explore nature in their immediate surroundings. These are easy to print and use open-source, adaptable activity sheets that can be used as fun teaching-learning tools in diverse geographies and across age-groups.

During the pandemic, we developed a series of bingo cards called “Hidden Housemates” to encourage exploring and discovering the living creatures residing in our homes, gardens, and office spaces.

At the same time, however, it’s important to acknowledge the reality of shrinking commons and community spaces, and the proliferation of no-go zones, particularly in cities. Children are often told where they should and shouldn’t go, even within local parks. This fractures their sense of belonging to their neighbourhood and limits their access to everyday nature.

An extension of our work in nature has been to engage with educators and families to demand access to commons, including neighbourhood parks and community spaces, that are becoming increasingly exclusionary.

2. As shared and interconnected

While nature education typically centres humans as the primary beneficiaries of nature, it must emphasise the shared use of resources by other life forms to encourage empathy and connection, among both students and teachers.

For instance, a chapter in a standard III Karnataka state EVS textbook says, “trees give us wood, food, and shelter.” Here, our modules and activities add what we think are the “missing nature” elements—that trees are also homes and sources of food for insects, birds, animals, and other plants.

We hope this framing prods teachers and student to think about caring for organisms that rely on and have the same rights over resources and spaces as humans, and that it fosters a sense of responsibility and respect for the intricate ecological processes that enable life, in all its different forms.

3. As a journey of discovery, not instruction

Because local natural systems are easily accessible and simple to observe and connect with, anyone, irrespective of disciplinary training, can impart nature education. Teachers often say that they cannot identify a plant or an animal and that they don’t know their scientific names. Here, a useful approach is to think about what a particular plant, animal or insect signifies for them or their students. Can they spot a cultural connection? Does one plant look different from another and why? Do all birds sound the same or fly in the same pattern? Do we see the same types of dragonflies in different areas and across seasons? All nature education requires is careful observation and an inquiry-based approach to learning.

Inquiry-based learning is a process of discovery and logical reasoning to understand the world. Instead of simply stating that a plant is a climber, a shrub, or a herb, teachers and students are invited to think about how and why the three differ from each other. It’s the process of coming to answers, and not just the right answer, that allows for learning to happen. This stands in contrast to what conventional education system prescribes, where the teacher often must impart facts and textbooks constitute the primary source of information. When the textbook is the primary medium of information, students don’t get the chance to make meaningful connections with the world around them.

4. As a part of existing coursework

Our nature learning framework continues to hinge on the EVS textbook. A major challenge in introducing more experiential and creative forms of learning lies in the fact that teachers are already burdened with curricula targets, administrative duties, and numerous compulsory capacity building workshops and courses throughout the academic year. Expecting them to on an additional burden to include nature-based lesson plans and activities has to be done with sensitivity, and by giving teachers agency to make decisions related to learning practices. Therefore, in the beginning, we do not expect them to learn an entirely new curriculum and methodologies of nature learning.

Unless we value and demand nature as an essential component of learning in our education spaces, our efforts will continue to be deemed as extracurricular or expendable.

Instead, we guide teachers to come up with ways to incorporate elements of nature learning into their existing lessons. For example, if a lesson deals with human senses, adding a nature learning element could involve introducing students to animal senses as well. Younger students could be given a visual depiction of the diverse sensory organs of various animals and encouraged to think about how they work, while older students could be led to more complex thinking: How do birds eat? Do they taste food like we do?

Nature is also the perfect tool to bring in an inquiry-based approach into our teaching-learning practices. We use methods such as role-play, natural history stories, and case studies, where we take a scenario from nature and assist teachers in breaking it down through a series of questions. We also work with teachers in developing lesson plans that have an inquiry-based learning methodology.

Unless we value and demand nature and nature learning as an essential component of learning in our education spaces, our efforts will continue to be deemed as extracurricular or expendable. By embedding it into the heart of our curricula and everyday teaching, we can ensure that our education spaces recognise and believe that nature and EVS education is not an expendable subject but is an inseparable part of our learning and life.

There are noticeable positive strides in this direction. The National Education Policy 2020, for instance, emphasises the importance of environmental education and provides guidelines, course content, and credit requirements for a mandatory EVS course. These efforts are complemented by the work of several educational and conservation organisations, as well as individuals working in and passionate about nature education. However, the journey is long. Like all education interventions, tangible change will require sustained effort, driven by demand, local activism, and policy shifts.

—

Know more

- Read this Ground Up story that highlights the stark difference in how children from rural and urban Tamil Nadu relate to their local biodiversity.

- Watch hands-on lessons and videos that bring nature into the classroom on Nature Classrooms’ YouTube channel.

- Read this article on understanding children’s connection with nature in a time of environmental loss.

Do more

- Explore the climate educator network’s open library for resources on nature education.