READ THIS ARTICLE IN

How phishing in Jamtara affects fishing in Tundi, Jharkhand

I am a project director at Sunita Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on skill development in rural Jharkhand. One of the areas that we work in is the Tundi block of Dhanbad, which is among the most economically backward blocks in the country. Most residents of this remote forested area, with a large indigenous population, live by farming one annual crop or as migrant labour in the Govindpur industrial area.

As a nonprofit working on livelihoods, we want to help the people secure alternate incomes through avenues such as pond fishery, mushroom farming, and beekeeping. However, the problem is that Dhanbad’s adjoining district is Jamtara, which has gained notoriety as the phishing capital for cybercrime. After incidents of cybercrime in the area, word about digital identity fraud has spread in 20–30 villages in the block. As a result, residents have become hesitant about sharing their details.

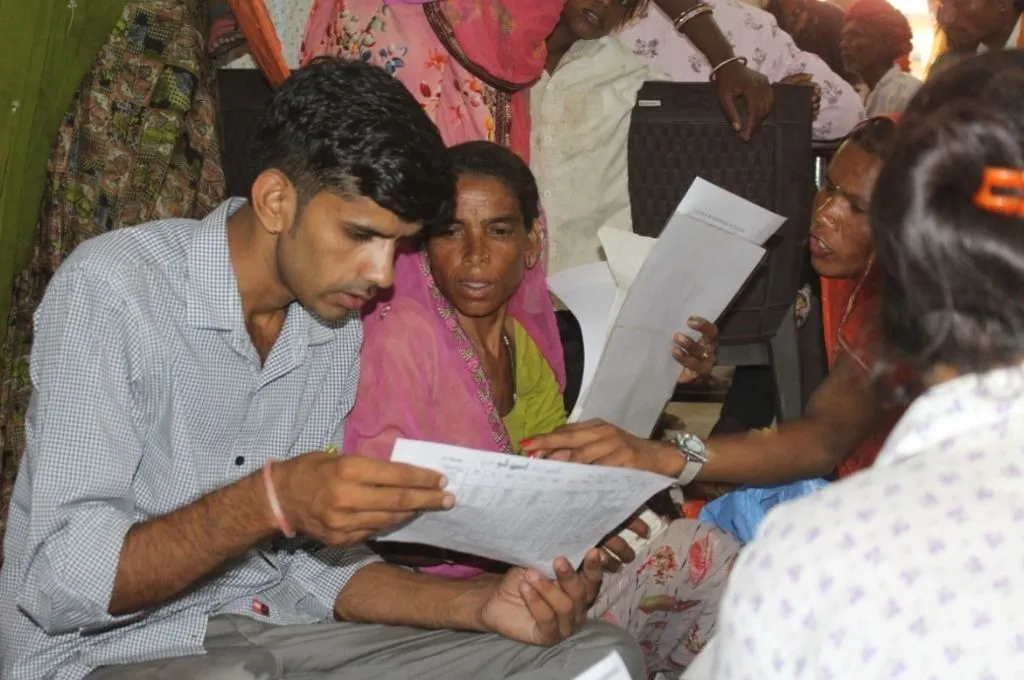

Due to the fear of getting scammed, locals refuse to share their Aadhaar card or bank details for Birsa Gram Vikas Yojana and Krishak Pathshala, a government-backed training initiative that we are working on. Even when they are too polite to tell us off outright, they pretend they don’t have Aadhaar cards or bank accounts. This has made our work difficult because I have to submit their documents at the district office for the courses we host at the institute along with the state government.

The Pathshala will be hosting programmes on fishery, agriculture, horticulture, and animal husbandry. To start the training, we need approximately 800 registrations from the 20–30 villages in the block. We have mobilised around 500 people so far. They don’t have photocopiers in the region and when we ask them for mobile phone photographs of their Aadhaar, they understandably get even more suspicious.

I am glad that these villages are vigilant because cybercrime is indeed a problem in this region. I live in Hazaribagh district and have had harrowing experiences with phishing too. I have received calls for fake lottery wins, and in one instance was told that my gas connection will expire if I don’t share my ATM pin. My father once gave away all his bank details. Fortunately, he became cautious when asked for an OTP.

I have worked on skill development programmes in Hazaribagh and Koderma districts of Jharkhand but have not faced this obstacle before. There, we provided mechanical or professional training, and the students understood that we were not running a scam. In Tundi, we have had to hire locals to help us reassure residents that we will not misuse their documents. We have made banners to spread awareness and created identity cards for farmers who register so they can trust us. Hopefully, we will be able to set up the training hall soon.

Giridhar Mishra works at Sunita Foundation, a nonprofit organisation focused on the empowerment of marginalised communities in Jharkhand.

Know more: Read about the impact of a rise in financial scams in Rajasthan.

Do more: Connect with the author at sfngoindia@gmail.com to learn more about and support his work.