With the introduction of the new Companies Act, 2013, India became one of the few countries to stipulate mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) spending. This landmark law was received with great optimism, and was expected to usher in a new era of corporate philanthropic giving in the country.

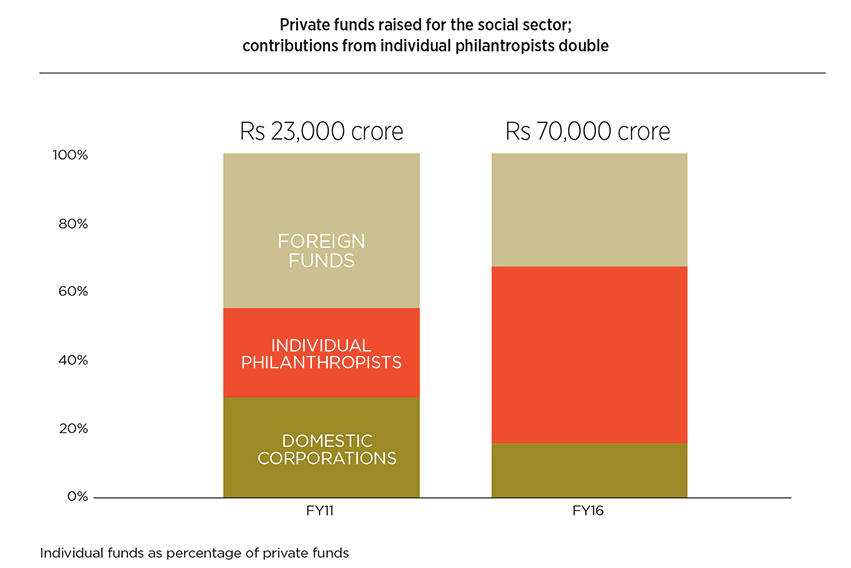

However, five years on, the story is a mixed one. Between 2011 and 2016, the quantum of philanthropic giving went up by more than 200%, from INR 23,000 crore to INR 70,000 crore, but this growth came largely due to the increase in giving from individual philanthropists. As a percentage share, the money coming from domestic corporations in that period went down from 30% to just about 15%, at Rs 10,000 crores.

Source: Bain India Philanthropy Report 2017 | Data from: Ministry of Corporate Affairs; MacArthur Foundation and Intellecap; Economist Intelligence Unit; proceedings in the Parliament of India, Lok Sabha; articles and editorials from India’s leading newspapers (The Hindu, Times of India, Economic Times, Mint, Business Standard, and others); Bain analysis

The Act in practice falls significantly short of its original legislative intent due to:

- Lack of clarity in the guidelines, enabling a high degree of self-interpretation.

- Almost no examples of action taken against non-compliance.

- Funding decision bias towards compliance vs. social impact.

Choices made around short-term projects are sub-optimal to solve the social issue.

The guidelines in the act focus more on governance than actual impact. As a result, boardrooms and CSR committees have come to think of CSR spends largely in terms of financial and quantifiable measures. Choices made are often around short-term projects and are sub-optimal to solve the social issue. For example, in the domain of sanitation, money is channelled towards building toilets vs. mindset change/education.

In this context, there is an opportunity—a need, really—for a paradigm shift in corporate India’s approach to giving. While this sounds ambitious, there is precedent for such evolution in thinking, for instance, in how human development is defined and measured today.

Measuring the ‘intangibles’

In the 1970s, most development approaches focused on narrow economic metrics like GDP as a guiding principle. Over time, development discourse broadened to take into account viewpoints such as Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach. And the real purpose of development was seen as improving the human condition and enlarging choices across the spectrum—economic, political, social, and cultural.

Photo courtesy: Carlos Muza on Unsplash

In 1990, the emergence of the Human Development Index (HDI) began to quantify key capabilities like access to health, education and goods; HDI rankings enabled us to unpack monetary/financial growth from the underlying objective of improving human lives. For eg. it revealed that Scandinavian nations had achieved higher improvement in the human condition than nations with much higher GDPs.

A Corporate Giving Index can play a similar role in broadening thinking around CSR in India. By including a broader set of parameters beyond pure spend, it can help set apart mission-driven, results focused companies and encourage the corporate sector to take a more meaningful approach to ‘making a difference’.

Related article: Making corporate giving effective

Developing a Corporate Giving Index (CGI)

The fundamental purpose of the CSR policy is to encourage companies to embrace their roles as corporate citizens. A CGI that takes an integrated reporting approach could help by capturing all elements of contributions and impact made, both within the company and on its economic and physical surroundings.

A CGI can help companies take a more holistic approach to managing their performance.

As with the HDI—it will foster ‘integrated thinking’, and have companies take a more holistic approach to managing their performance by looking at impact on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) parameters as well. A CGI can help achieve the following:

- It can account for employee involvement beyond funds. Currently, most CSR decisions are driven by what the CEO cares about, and the process does little to seed the idea of corporate responsibility amongst its employees. By measuring employee involvement, the commitment to broader social issues can be reinforced. This can further be tied to employee awareness and actual engagement (measured perhaps by time given to the cause).

- Second, it can capture a company’s depth of engagement with a cause. For eg. hiring people with disabilities—if this is a cause the company supports; or how sustainable a firm’s production lines are if environment is a an area of focus for them.

- Third, it could capture non-financial contributions such as market linkages and access created for the nonprofits and causes it supports.

A great first step in this direction is SEBI’s call last year for the top 500 listed Indian companies to undertake integrated reporting. This came along with a commitment from the BSE to build integrated reporting in their corporate governance scorecard, to assess companies listed on their stock exchange.

Challenges to the CGI

HDI’s success was in a large part, due to its transparency and simplicity. However, the HDI we see in use today is the product of nearly 30 years of evolution and readjustment. The CGI too will have its own process and pitfalls along the way. How these are manoeuvred through will define not just its own effectiveness and usage but more broadly, how seriously Indian companies take corporate social responsibility. Here are some risks to look out for:

- Lack of clarity. For example, the SEBI call for integrated reporting comes without guidelines on what this report would include and how it should be implemented. It runs the danger therefore of varied piecemeal efforts by companies, and as a result an inability to benchmark performance across them.

- Too many standards. Several indices are in use globally, each capturing a different aspect of social performance and sustainability. Companies cannot spend their time reporting to each one, and currently there is no cross comparison possible between indices. The first phase of CGI evolution must therefore necessarily address the need for one consolidated index.

- Risking the good, in search for perfection. Much debate abounds on getting the process right. A basic, simple model – widely implemented and used, must be instituted quickly – even if it runs the danger of oversimplification.

For eg. it is difficult to capture as a number ‘how much a company cares for the environmental impact of its manufacturing processes’. Proxy indicators that measure for important aspects of the manufacturing process, its impact on the environment, and so on, will help. It will not be perfect. The process of coming to a set of indicators that apply various industries will then require many iterations and adjustments. This process of refining and streamlining is wholly necessary to create a robust index, but can only begin once a basic model is embraced.

In addition to bench marking the efforts of socially driven companies, the CGI will help them to attract potential foreign SRI (socially responsible investments) as well as attract and retain talent. For the development sector, it would mean access to funds backed by deeper commitment to their social objectives, which in turn would allow for better long-term goal setting and planning.

The time is ripe for us in India to take this next step that will change the way in which companies engage with the social environment around them.