Every intervention to improve a social situation involves an unsettling of the status quo – and these disruptions may impose new costs for some members of a community or elements of an ecosystem. For example, replacing plastics with organic cotton tote bags to save marine lives sets as a condition for success the need to use the cotton bag 20,000 times to truly offset the high water costs of growing organic cotton.

Yet when the impact of social entrepreneurs and innovators is being measured, there’s a tendency to avoid assessing the full range of positive and negative impacts, and to only focus on whether there are measurable effects within the “good part of the impact spectrum.”

Ironically, the more subtle an organisation’s overall web of impacts, the more energy is usually spent evaluating its positive social outcomes, leaving far less bandwidth to examine its potential negatives.

In contrast, when a bold intervention model sets off a chain of easily observable effects – especially effects that feed into other social contexts – it is more likely to be judged based on the full spectrum of its impacts, both positive and negative, simply because the task is simpler. That means these more noticeably impactful interventions are less likely to benefit from the assumption that any negative externalities are unrelated to their work. They get less benefit of the doubt.

The paradoxes of scalability

This inevitably leads us to a paradox: The more concrete the effects of an intervention, the higher the likelihood that it will be penalised for negative externalities and bad side effects. Meanwhile, intervention models that address less visible issues – or that have more diffuse (or less significant) impacts – get a pass.

In pushing for scale, many sacrifice innovation.

Unfortunately, this triggers another paradox: Scaling requires simplification and standardisation. And because it is easier to simplify, market and mobilise around a concrete impact, the interventions that generate this degree of impact are far likelier to be scaled. Yet knowing that they’re more likely to be penalised for any negative side effects, and realizing that the experimentation that drives innovation can make these side effects more likely, proponents of highly scalable interventions are also likely to be less experimental in their approach, and thus more risk-averse. So in pushing for scale, many sacrifice innovation.

Related article: Questioning scale as we know it

There is nothing wrong with a risk-averse, low-innovation, highly concrete intervention. Most soup kitchens fall in this category, to take just one example, and they do very important work. But when social interventions are expected to be “innovative” – by the industry press, funders, governments, prize committees, and other intellectual validators – then we suddenly have a problem with boring but effective models. Many interventions and businesses find themselves in a Catch 22: They need to show that they’re both innovative and scalable – but being scalable makes it harder for them to be innovative.

No easy solution

This can be a vexing problem for a social enterprise or intervention to solve. To satisfy impact evaluators that they’re thinking seriously about the effects of their actions on the broader ecosystem or community, entrepreneurs may attempt to lessen the concreteness and simplicity of their models – thereby reducing not only their negative externalities, but also their positive impact.

And, in sincerely seeking to be prudent, they may try to thoroughly anticipate the consequences of their actions as widely as they can, then pre-empt them with secondary interventions. This can end up adding more layers to their operational model, weighing it down with complexity and further diluting its effectiveness.

This type of root cause analysis often requires an assessment of the complex policy, political and social-psychological structures that influence the community within which an intervenor is working. Yet the more the intervenor retreats from the observable problem to focus on these upstream structural factors, the harder it becomes to embrace simplicity and the comforting focus on concrete problems.

Picture courtesy: Pxhere

The reward, of course, is that impact measurement picks up fewer negative externalities, because the feedback loops become too complex, and the intervenor benefits from the latent assumption that any negative impacts are unrelated to the intervention.

For example, it is hard to miss the fact that soup kitchens can create dependency, so evaluators are very likely to want to see a soup kitchen do more than just handing out soup to the homeless – they may also expect it to help beneficiaries to “graduate” from the need. On the other hand, evaluators of a capacity building program on bias detection for municipal welfare officers might overlook their suspicion that the program may just be making welfare officers better at hiding their biases: The psychological elements of such an assessment are simply too abstract, even subjective, to easily measure.

Entrepreneurs and innovators constantly feel the pressure not to propose solutions that are too bold or too concrete.

These dynamics point to a subtle but powerful law of social innovation: The less concrete the causal chain to impact, the more likely it is that the social entrepreneur can also fudge around the unintended consequences. The more concrete and simpler the intended results from the change model or intervention, the more concrete the “side effect risks” become – and the higher the likelihood that evaluators take them into account when evaluating cost-benefits. Entrepreneurs and innovators in the social impact space thus constantly feel the pressure not to propose solutions that are too bold or too concrete.

The trade-off to this risk-averse approach, naturally, is that it makes scaling less likely. It is harder, for both the ecosystem and the intervening enterprise, to find innovators and change agents who are cognitively and temperamentally suited to the task of intervening in complex, deep, societal structures upstream from the problems that excite them – while at the same time offering bold and innovative solutions. And even when innovators do try to tackle complex systems upstream from their main focus areas, they often find that their models aren’t robust enough to cause actual change in these systems – or their measurement tools aren’t sophisticated enough to measure these changes.

Building the kind of measurement tools that can minimise greenwashing in these cases is so much harder to do, and the impact so much less measurable, than simply coming up with a more superficially impactful product. It’s easier to just intervene downstream and ignore complex unintended consequences – hence the proliferation of organic cotton tote bags.

Related article: How do we think about scaling up?

So, it is not hard to see why funders – even those with a social impact bias – would normally prefer to back a well thought-out product with a simple business plan, regardless of high negative externalities, rather than a complex, systems-focused intervention designed to affect entire communities or ecosystems. It’s also easy to see why impact auditors tend to prefer the opposite approach.

And therein lies the source of a brewing civil war in social innovation, between funders keen on clear models and evaluators who insist on complex interventions. In the impact investment space, where both returns and “covering all the bases of impact” are supposed to be equally important, confusion easily sets in as this expectations mismatch grows more intense. And the end result is a reduction in the ability of impact investing itself to scale up to meet demand.

Addressing the trade-off trilemma

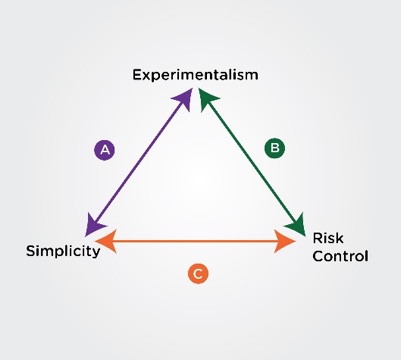

Simplifying the above discussion leads us to a framework for understanding these trade-offs, and the trilemma they represent. Social innovators are confronted with the three strategic choices of simplicity/focus, risk-avoidance/integrity, and experimentalism/disruption.

Picture courtesy: Next billion

It is hard for all innovators – but, I argue, more so for social innovators – to abide by the usual entrepreneurial maxim of focus when they are also penalised for all the risks they leave unmitigated in the social setting. And it is just as hard for them to experiment in search of ways to minimize their negative footprints if focus is indeed essential for scale. It is a situation that forces them to “pick two, any two, but never the third.” What’s more, even after a social innovator has made a strategic choice, shearing forces operating between these different strategies continue to pull them in opposite directions, obstructing the growth of social enterprises and reducing talent inflow into the social innovation sector.

Related article: The dirty secret of social enterprise: Scale is overrated

I believe that these shearing forces are responsible for fragmenting an ecosystem that really only works effectively when working together. They account for the fact that, though 60% of young graduates now assert a preference for working for organisations with a “purpose,” this hasn’t really translated into considerable expansion of the social innovation sector – nor proportionately strengthened its influence in the design of public policy, even in areas where the unique value proposition of the sector is compelling.

While the path to addressing these tensions, trilemmas and shearing forces has not yet been established by empirical research-backed analysis, there is one obvious direction the social innovation community around the globe can look for inspiration: socialising impact responsibility.

Social innovation faces the real risk of becoming an elitist – and shrinking – club.

Right now, most evaluators and auditors begin from the assumption that innovators bear the sole responsibility for mitigating the risks generated by, or arising in the wake of, their interventions. The bar has been set so unrealistically high that only a priestly caste of the most temperamentally and cognitively equipped practitioners can mobilise the goodwill, support and validation they need to tackle large-scale problems. Social innovation thus faces the real risk of becoming an elitist – and shrinking – club.

Imagine instead if an alternative approach to risk mitigation took hold – one that emphasised a social accountability model rooted in ecosystems, where funders and backers took a portfolio-wide approach to determine how the responsibility for risk management would be shared through synergies across their whole portfolio. If this macrocosmic problem-solving approach were to take root, I am certain that intervenors would be bolder in exploring more daring paths to scale, without sacrificing moral intent, integrity and responsibility for the unintended consequences they generate.

This proposed combination of agility, social risk portfolio design, social accountability and transparency about ethical assumptions would also promote a healthy balance between concrete and systemic/structural interventions, while strengthening the linkages among these different approaches and enabling them to address social problems with far more impactful outcomes.

Hopefully, further research and field testing will shed more light on what works over time, opening new paths to experimentation, innovation and impact at scale.

This article was originally published on Next Billion.