Background

Civil society organisations, including NGOs, community groups, and academic institutions, rely heavily on data for research, advocacy, and welfare initiatives. However, as these organisations face increasing scrutiny on multiple fronts, the new data protection law presents a potential challenge. The Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy has categorised these organisations into two broad types: service delivery organisations and rights and advocacy organisations. Given the growing importance of data in their day-to-day operations, a strong grasp of data protection laws can act as a shield for civil organisations, protecting them from potential legal challenges. The release of the Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 (“Draft Rules”), which aims to operationalise the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“Data Protection Act”), marks a critical moment. These rules are currently open for public consultation [you can send your comments here till February 18, 2025], presenting an opportunity for organisations to understand and engage with the new regulations.

What makes you a Data Fiduciary?

The Data Protection Act says that a “data fiduciary” is someone who decides, either alone or with others, how and why personal data will be processed [Section 2(i)]. The Data Protection Act will only apply to you if you are processing personal data in India, which is collected digitally or first collected in a non-digital form and later digitised [Section 3]. So, if you are the one deciding how personal data will be handled, and you are processing it within India (either in digital or digitised form), then yes, you would be considered a Data Fiduciary.

1. Who is a Data Principal?

A Data Principal is a person whose personal data is collected and processed by a Data Fiduciary [Section 2(j)]. In the context of civil society organisations and NGOs, the beneficiaries, donors, and volunteers would be considered as the Data Principals.

2. Does nationality matter? Where should your organisation be based or operate for the law to apply to it?

The nationality of your organisation does not matter. The Data Protection Act applies to the processing of personal data within India, as well as outside India if the processing is related to offering goods or services in India. This means that foreign organisations must comply with the Data Protection Act when processing personal data connected to activities in India, regardless of their location or the nationality of the organisation.

3. But what is a Data Processor? Is that something different from a Data Fiduciary?

Unlike data fiduciaries, Data Processors act as subordinate entities that process personal data on behalf of data fiduciaries, following their instructions and guidelines [Section 2(k)]. Data fiduciaries decide how data is handled, while processors follow those instructions. In some cases, one entity may act as both.

What are your obligations?

As civil society organisations or NGOs, you may have sensitive personal data including donor information, beneficiary details, and volunteer records. Given the personal nature of this data, unauthorised collection, access or misuse can result in discrimination, identity theft, or emotional distress. Now that you have identified your role as a Data Fiduciary, it is essential to understand and fulfill the obligations required to protect this sensitive data.

1. Give them notice

The Data Fiduciary must provide a clear and simple notice to the Data Principal before obtaining consent [Section 5]. This notice should include an itemised, easy-to-understand explanation of the personal data being collected, the purpose of its collection, and how the Data Principal can withdraw consent, exercise their rights, and file a complaint with the Data Protection Board, constituted under the Data Protection Act [Section 5, Rule 3]. The notice should be available in English or any language specified in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution [Section 5(3)].

2. Take explicit consent

After providing notice, when requesting consent, the Data Fiduciary must present it in clear, plain language and offer the option to access the request in English or any language under the Eighth Schedule. Contact details of a Data Protection Officer or authorised person must be provided for any communications regarding rights. The Data Principal can withdraw consent at any time, and the process should be as easy as giving it. Withdrawal will not affect the legality of prior data processing based on consent [Section 6].

3. What is a consent manager?

A consent manager is a registered entity that helps individuals manage their consent for processing personal data [Section 2(k)]. Acting as an intermediary between Data Principals, Data Fiduciaries, and data requesters, consent managers ensure that only the agreed-upon data is shared securely. They must meet strict registration requirements, including being incorporated in India, having a net worth of Rupees 2 crore, and adhering to technical, financial, and operational standards to protect data privacy and security.

Consent managers must provide consent management tools, ensure security, avoid conflicts of interest, and retain records for seven years. They must ensure consent is informed and easy to withdraw, avoid subcontracting or transferring control without approval, and publish ownership details while conducting regular audits and reporting to the Data Protection Board [Section 6(7), (8)&(9)].

4. Data collected before the Data Protection Act is enforced

If your organisation did not originally give notice and take consent at the time of establishing the data-collection pipeline, the Data Protection Act provides for a comparable notice, to be provided as soon as it is “reasonably practicable,” after the Data Protection Act comes into effect. The law does not define a specific timeframe for such retrospective notice and consent, and leaves it as subjectively “reasonable” [Section 5(2)]. The notice and consent obligation can be fulfilled online, or offline as long as the necessary information about data usage and privacy is clearly communicated.

5. What can be processed?

A Data Fiduciary can only use the personal data for the specific purpose that the Data Principal has agreed to [Section 4(1)(a)]. Data may also be processed for certain “legitimate uses” [Section 4(1)(b)]. If the Data Principal has not withdrawn or refused consent, the Data Fiduciary is allowed to use the data as originally intended. Additionally, there are no legal obligations to process personal data that is made publicly available [Section 3(c)].

6. Take reasonable security safeguards

The Data Fiduciaries need to take reasonable security measures [Rule 6], which include:

Data Protection: A Data Fiduciary must protect personal data in its possession, including data processed by a Data Processor on its behalf, by implementing reasonable security safeguards to prevent breaches.

Security Measures: Implement appropriate safeguards such as encrypting, obfuscating, or masking personal data, or using virtual tokens. Control access to computer resources used by the Data Fiduciary or Data Processor, and monitor, log, and review access to detect and remediate unauthorised access.

Access Monitoring: Maintain visibility on data access through logs and monitoring systems to detect, investigate, and remediate unauthorised access to prevent recurrence.

Continued Processing: Implement measures, such as data backups, to ensure continued processing if confidentiality, integrity, or availability is compromised.

Retention of Logs and Data: Retain logs and personal data for at least one year (unless otherwise required by law) to detect unauthorised access, investigate, and remediate.

Contracts with Data Processors: Include provisions in contracts with Data Processors to ensure they implement reasonable security safeguards.

Technical and Organisational Measures: Ensure effective observation of these security safeguards through appropriate technical and organisational measures.

7. Other obligations

Some of the other obligations, you as a Data Fiduciary, need to fulfill are:

Data Retention & Deletion: Retain data only as needed, and delete it once the purpose is served, or if the consent is withdrawn, unless its retention is necessary for compliance with any law for the time being in force. The Data Fiduciary should inform the Data Principal about the data erasure at least 48 hours in advance. [Section 8, Rule 8].

Accountability: Be responsible for all data processing activities and appoint Data Processors under valid contracts [Section 8].

Grievance Redressal: Provide a mechanism for resolving Data Principals’ complaints [Section 8].

Notification on Consent Changes: Inform Data Principals about changes in consent or processing terms [Section 8].

Communication & Support: Offer contact details for addressing Data Principals’ concerns about data processing [Section 8, Rule 9].

Data Breach: In the event of a personal data breach, the Data Fiduciary shall give the Board and each affected Data Principal, intimation of such breach [Section 8].

Apart from the obligations under the Data Protection Act, as per the 2022 Directions by Computer Emergency Response Team (“Cert-IN”), it is also important to follow any orders/directions by Cert-IN for cyber incident response, protective and preventive actions.

8. What if you are declared a Significant Data Fiduciary?

The Central Government may notify any Data Fiduciary or a class of Data Fiduciaries on the basis of some factors which are – (a) the volume and sensitivity of personal data processed; (b) risk to the rights of Data Principal; (c) potential impact on the sovereignty and integrity of India; (d) risk to electoral democracy; (e) security of the State; and (f) public order [Section 10].

There are additional obligations if you are declared a Significant Data Fiduciary [Section 10 and Rule 12]:

Appoint a Data Protection Officer (“DPO”): The DPO must represent the Significant Data Fiduciary, be based in India, report to the governing body, and handle grievance redressal.

Annual Data Protection Impact Assessment & Audit: A Significant Data Fiduciary must conduct these annually to ensure compliance with the Data Protection Act.

Report Submission: The person conducting the assessment and audit must submit a report with significant findings to the Board.

Algorithmic Software Diligence: A Significant Data Fiduciary must ensure algorithmic software used does not pose risks to Data Principals’ rights.

Data Transfer Restrictions: A Significant Data Fiduciary must ensure that personal data specified by the Central Government is not transferred outside India.

What about children’s data?

1. Who is a child?

The Data Protection Act defines a child as any person who has not completed 18 years of age [Section 2(f)].

2. Can you process their data?

If your organisation collects data from children, you must ensure that you obtain verifiable parental consent before processing any such data. As the Data Fiduciary, it is your responsibility to verify that the individual providing consent is indeed the child’s parent or legal guardian and can be identified if necessary, in compliance with relevant laws. You can do this in two ways: (a) by using reliable identity and age details that your organisation already holds, or (b) by using voluntarily provided identity and age information, or a virtual token issued by a government-authorised entity (such as DigiLocker).

The Draft Rules imply that the child will either self-declare their age or the parent/legal guardian will inform your organisation about the child’s status. However, it is important to exercise due diligence to ensure that the individual providing consent is not a minor, otherwise the penalty for processing children’s data can be up to Rupees 200 crore. The process of confirming the relationship between the parent and child is still unclear.

3. What is prohibited completely?

Data Fiduciaries are prohibited from processing children’s personal data in ways that could harm their well-being, including activities like tracking, behavioral monitoring, or targeted advertising aimed at children [Section 9(3)].

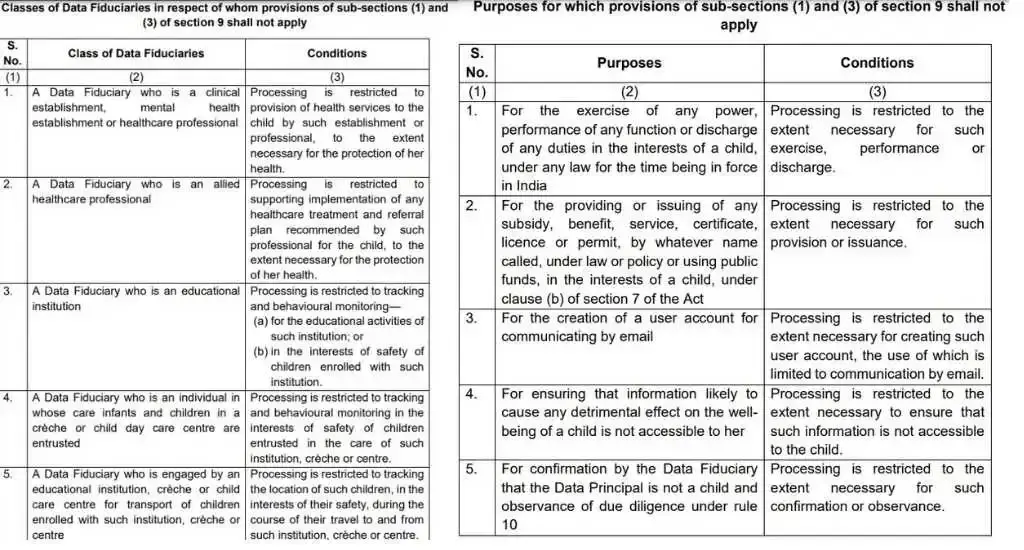

4. Are there any exemptions?

Exemptions to the requirement for verifiable parental consent and behavioral monitoring may apply depending on the class of Data Fiduciaries or the specific purposes for data processing. These exemptions are outlined in Part A (for classes) and Part B (for purposes) of the Fourth Schedule of the Draft Rules [Section 9(5), Rule 11]. If you fall in either of these categories, you may be exempted, however, the processing must be limited to what is necessary for the specific purpose.

The Central Government can also exempt a Data Fiduciary from these restrictions if they prove their processing methods are safe, and it may set a minimum age for when these rules no longer apply.

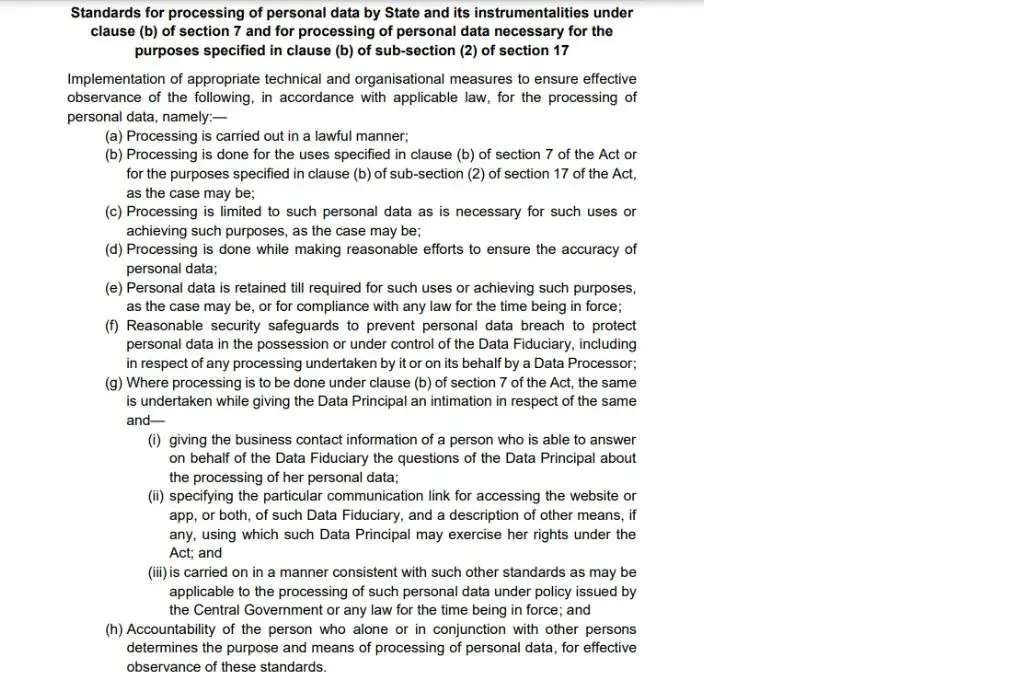

Are civil society organisations or NGOs exempted under the Data Protection Act?

Not specifically, but if your organisation is involved in research, Section 17(2)(b) of the Data Protection Act provides an exemption that allows you to process personal data for research or statistical purposes. This means that in many cases, you can use personal data for research without needing to comply with the law. This exemption comes with specific conditions. Data Fiduciaries must ensure that personal data is processed lawfully and only for specified, necessary purposes. They must prioritise data accuracy, implement robust security measures, and retain data only for as long as required. Additionally, the Data Fiduciary or designated responsible parties are accountable for meeting these requirements. It is to be noted that we are yet to have clarity on what exactly amounts to “research and statistical purposes”.

However, there is an important catch: if the data you process is used to make decisions about a specific individual (like profiling them or making recommendations), this exemption will not apply [Section 17(2)(b)]. In such cases, you will have to follow the full data protection requirements, including obtaining explicit consent from individuals, ensuring transparency, and protecting their rights. So, while this exemption can make research easier by relaxing some requirements, you must be careful not to use the data in a way that could affect individual decisions.

What to do in case of a data breach?

1. What is a data breach?

It refers to any situation where personal data is used or handled without permission, or when something goes wrong by accident. This can include instances like unauthorised sharing of personal information, someone gaining access to data they should not, using data in ways that are not allowed, accidentally altering or destroying data, or losing access to personal data altogether. In these situations, the safety, privacy, or reliability of the data is compromised, making it vulnerable or less trustworthy, which can lead to serious consequences for individuals and organisations [Section 2(u)].

2. What do you do if there is a data breach?

In the event of a breach, organisations have to inform the Data Protection Board (the privacy regulator established under the law) and the affected individuals. Failing to report a data breach could lead to the Data Protection Board imposing fines of up to Rupees 200 crores. The Data Protection Board can also fine companies that do not put in place “reasonable” security safeguards to protect personal data up to Rupees 250 crores.

3. Informing the Data Protection Board

Data Fiduciaries must inform the Data Protection Board of data breaches without delay, providing a breach description, circumstances, mitigation measures, findings on the cause, remedial actions, and notifications sent to affected individuals. They must submit this information within 72 hours, though an extension may be requested in writing.

4. Informing the affected Data Principals

When a data breach occurs, organisations have to promptly notify affected individuals in a clear and concise manner, using the contact details the person has registered with the company, such as their account, email, or phone number. The notification must include details about the breach, its impact, steps being taken to address it, security measures for individuals to protect themselves, and contact information for queries.

5. Does Cert-IN need to be informed?

Yes, Cert-IN will also have to be informed, as per their 2022 Directions.

What about the Information Technology Act, 2000?

While the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 (“SPDI Rules”) were among India’s early attempts to address data protection, they were primarily designed for cybersecurity and e-commerce, rather than personal data privacy. They also lacked essential provisions for modern challenges like cross-border data transfers, informed consent, and grievance redressal mechanisms. Moreover, the IT Act’s focus on “information” rather than the broader concept of “data” became increasingly inadequate as digital complexities evolved. In response, the Data Protection Act represents a significant leap forward, offering a more detailed and enforceable framework for data protection. Once enacted, Section 44(2) of the Data Protection Act will repeal key provisions of the IT Act, including Sections 43A and 87 (2)(ob), and the SPDI Rules.

What are the probable challenges that your organisation can face?

1. Compliance with the notice and consent requirement

If you are working in rural areas, obtaining consent and providing proper notice about data collection can be a significant challenge. People in rural areas may not fully understand the concept of personal data or the implications of giving consent. Organisations working in rural areas often work with marginalised communities, where trust is crucial, and it can be challenging to ensure that consent is truly informed and voluntary. Furthermore, delivering clear, understandable notices about data processing practices in a way that is accessible to people with different levels of education and technological access can be a complex task. This can create obstacles in complying with data protection laws, as organisations may struggle to balance legal requirements with the need to engage effectively with these communities.

2. Surveillance based on data requests

You may be asked to provide information to the Central Government when requested under Section 36 of the Data Protection Act and Rule 22 of the Draft Rules. This provision raises significant surveillance concerns for organisations, especially those working with marginalised or minority communities. As these organisations often handle sensitive personal data, such as that of vulnerable groups, they may face pressure to disclose information to the government, potentially exposing individuals to discrimination or harm. The requirement to provide data could lead to the surveillance of communities, especially if the data is used for political or security-related purposes. Additionally, national and international donors who support such organisations may be reluctant to fund projects if they fear that their financial contributions or the data of beneficiaries could be scrutinised or used against them. This can undermine trust, limit donor support, and jeopardise the protection of vulnerable groups.

3. Increased costs and infrastructural burden

The Data Protection Act and Draft Rules will require organisations to invest in secure data storage, encryption, and compliance tools, which can be costly. They also need to allocate resources for staff training, legal expertise, and handling data access requests or breaches, diverting time and money from their core activities. As these organisations may struggle to comply with stringent regulations without adequate resources, the big penalties under the Data Protection Act creates another significant burden, especially for smaller organisations.

4. Dilution of the Right to Information Act, 2005

The Right to Information Act, 2005 (“RTI Act”) forms the backbone of much of the work for civil organisations, providing them with essential information to advocate for transparency, hold authorities accountable, and ensure that resources and policies are being used effectively for public benefit. Unfortunately, Section 44(3) of the Data Protection Act amends Section 8(1)(j) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, to include “information relating to personal data.” This amendment raises serious concerns, as it risks undermining the Right to Information Act, 2005, by enabling authorities to withhold crucial information under the pretext of protecting privacy. This could create a loophole that allows authorities to evade transparency and scrutiny, particularly in cases involving corruption, ultimately weakening the very foundation of accountability that RTI was designed to uphold.

Conclusion

While the Data Protection Act and the Draft Rules are essential for safeguarding data privacy, their vagueness leaves room for executive discretion, potentially used to target dissenting opinions. Civil society organisations must not only understand their obligations but also actively engage in the ongoing consultation to address these ambiguities and protect their work from misuse of the law.

This article was originally published on Internet Freedom Foundation.