Malaya village, under Kamalpur subdivision in Tripura’s Dhalai district, is predominantly inhabited by the Meitei Pangal (Manipuri Muslim) community. It sits on the bank of Dhalai River along the Indo-Bangladesh border, separated from the neighbouring country only by a fence. According to locals, 250 families reside in Malaya, which has a population of approximately 1,000.

Sajabam Ismail, a Metei Pangal and former principal officer of the village committee at Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council (TTAADC), says, “The name Malaya comes from a type of fish. According to village elders, the paddy fields in Malaya were once submerged in water from the Dhalai River. A fish called mola (locally known as moka mach) was commonly found in these waters, which is how the village got its name.”

The Meitei Pangal community primarily resides in Manipur, but like other Manipuris, many migrated to Tripura and nearby areas in what is now Bangladesh during the ‘Seven Years of Devastation’ (1819–26), when the Burmese invaded Manipur. “Before settling in Malaya, our ancestors lived on the other side of the Dhalai River, in Kamalganj and Sylhet, which are now part of Bangladesh,” says Ismail.

He further explains, “Even today, there are Pangal villages such as Mukabil across the river [in Bangladesh]. Our ancestors chose to settle in Malaya because they did not want to live under the oppressive zamindari system. They preferred the Tipperah kingdom over the zamindars.”

However, there are no exact records of when the Pangals first settled in Malaya. Ismail shares, “Many village elders say that our settlement in Malaya coincided with the construction of the Dhalai Club, built by the East India Company in present-day Bangladesh. When I travelled to Bangladesh three decades ago, I saw a signboard stating that the Dhalai Club was established in 1848. This suggests that the Pangals settled in Malaya before 1848.” The village masjid, a significant landmark, was constructed in 1853. Interestingly, historical documents note the arrival of Muslims in neighbouring Manipur between the early 1700s and 1850s.

Livelihoods on the move between India and Bangladesh

Before the Partition of India, the residents of Malaya used to travel freely across the Dhalai River. Locals say that they still have many relatives on the other side, but since the creation of the international border, it has become difficult to travel without proper documentation.

The villagers reminisce about how, in the past, they attended festivals and intermarried with people from villages across the river. “After the border division, these cultural exchanges stopped,” says Ismail.

However, while modern geopolitics have restricted cultural interactions, the peculiarities of the Partition continue to make cross-border travel a necessity for the Pangals in Malaya.

Because of the way the borders were demarcated, many villagers’ land falls inside the fencing. The Pangals, largely an agricultural community, depend on those lands for their livelihoods. The locals I spoke with stated that they are given a card by security personnel, allowing them to work on the land inside the fencing for a fixed number of hours every day. But this process has limitations. Many said that they prefer to work early before the sun’s rays become as harsh as they are during midday.

Many young Pangals are now looking for alternatives beyond farming which was once their primary occupation. They are also migrating to foreign countries for work. “Among all the Pangal villages in Tripura, Malaya has the highest number of non-resident Indians (NRIs),” Ismail states.

Why are young people leaving Malaya?

Salauddin migrated to Saudi Arabia and lived there for 13 years before moving back to Malaya. Explaining his decision to leave, he says, “After multiple failed attempts to join the armed forces, I decided to go to Saudi Arabia for work in 2009, just after my marriage. I was working as a tailor and the income wasn’t sufficient for our family—I wanted to earn a better living. After migrating to Saudi Arabia,I started working as a storekeeper.” He further adds, “My son studies at Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya, a few hours from the village. I returned when he was in class 8 because it became difficult for my wife, Minara Khatun, to manage everything alone. Now I own an electric rickshaw.”

Salauddin highlights the lack of educational infrastructure in the village. “Education is highly competitive today, but our village’s school infrastructure is falling behind,” he shares.

Noor,* a former student of Malaya S B School, provides insights into the history of education in the village. “The school was established in 1930. Initially, it only had classes 1 to 4. In 1979, class 5 was added, and in 2007, it was further upgraded to class 8,” he says.

Despite being decades old, the school in Malaya has yet to expand to include class 10. It has only four teachers, including the headmaster, for a total of 64 students. The villagers I spoke to mentioned, that they prefer private schools for better education, so the number of the students has declined over the years. Even today, after class 8, students must travel 3–4 kilometres to continue their education.

Many young people go to other areas for higher studies due to such infrastructural issues. Ismail says, “Malaya S B School is a Bengali-medium school. It would be more beneficial for children if the government changed the medium of instruction to English. It should also, of course, improve the infrastructure.”

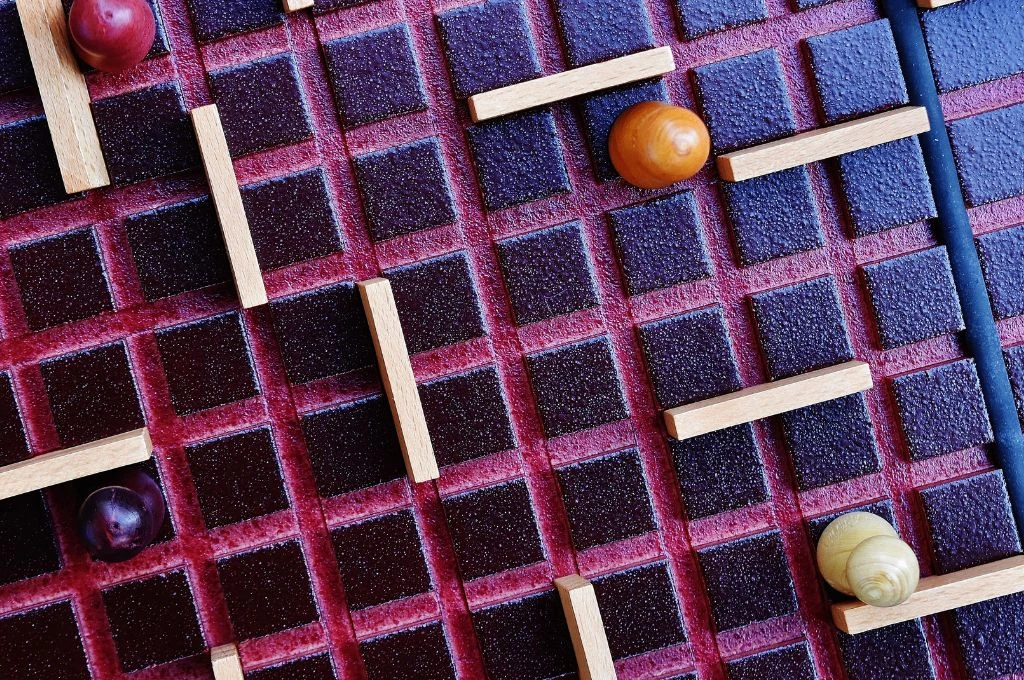

According to him, the government should also invest in women’s livelihoods. “Pangal women are very skilled at weaving and make clothes for themselves. They know how to create traditional attire with motifs such as ningthou phee and kangthon pheeda. If they also knew how to sell their work, they could earn a living.”

For this to happen, the government will have to invest in training programmes that teach women how to blend traditional designs with contemporary tastes. It must also help them connect with the local market. However, this would require the state government to change its outlook and see Malaya as a place of opportunities rather than one of scarcity.

*Names changed to maintain confidentiality.

—