India is home to 7–8 percent of the world’s flora and fauna, with more than 1,04,561 species of fauna and 55,387 species of plants documented here. The country’s unique geographical and climatic variations have nurtured a variety of ecosystems, making it one of the 17 mega biodiverse nations in the world. India also harbours four of the world’s 34 biodiversity hotspots—the Western Ghats, the Himalayas, the Indo-Burma region, and Sundaland.

Despite this, our approach to conservation remains largely focused on a few species of mega-fauna rather than on the ecosystem as a whole.

The Nature Conservation Index (NCI), released in October 2024, supports this view. The survey, which measured conservation efforts in 180 countries, assigned India a score of 45.5 on 100, placing it near the bottom with a rank of 176. The NCI is only one of the many alarm bells that have been ringing in recent years to alert us to the gaps in our conservation approaches.

Conservation needs to look beyond tigers

Project Tiger was launched in 1973, a year after the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972 was passed, to halt the dwindling tiger numbers. Fifty years later, the programme includes 57 tiger reserves, covering more than 82,000 sq km. The All India Tiger Estimation (AITE) of 2022 recorded an estimate of 3,682 wild tigers, a significant increase from the estimate of 1,827 in 1972. As a tiger conservation programme, the scheme has been hailed an all-out success. But as a broader wildlife conservation programme, which it is meant to be, it is perhaps less so.

Project Tiger was designed not to protect the tiger alone, but the entire forest ecosystem. The guiding principle was that conservation of the apex predator would necessitate protection of its entire habitat. However, the success of Project Tiger is solely measured by the increase in the number of tigers and not by the comprehensive ecological health of the tiger’s habitat that comprises other fauna (including fungi, plants, birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects, and arachnids). Over time, the programme seems to have strayed from this central tenet.

A classic example is that of Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR), which boasts of approximately 260 tigers (as per AITE 2022)—the highest count for any tiger reserve in India. Now, CTR also hosts hog deer that require the tall terai grasslands for their survival. Both these species are listed in the IUCN Red List as endangered. However, while years of habitat management have prioritised the needs of tigers by ensuring the population increase of spotted deer, the revival of the hog deer population in CTR did not gain steam. The construction of Ramganga Dam at Kalagarh, around the time that Protect Tiger was launched, inundated a large part of CTR’s terai grasslands. No scientific studies have been done, but observations by well-known wildlife biologists suggest that there are fewer than 100 individuals of hog deer in CTR. It is therefore necessary to reassess our management practices, as conservation of both tiger and hog deer is equally important.

Conservation should not be a numbers game

The success or failure of a conservation programme invariably boils down to the numbers—the population count of the species at the heart of the programme. But when the population count of a single species is the primary measure of success, it creates tunnel vision and leads to a host of challenges, such as:

1. Problem of plenty

One of the most important considerations for any species conservation programme is the carrying capacity of a habitat. The tiger reserves cover only 21 percent of the 3,80,000 sq km of forests in India that can support tigers. The overall distribution of tigers in tiger reserves is disproportionate, with some areas having significantly low tiger occupancy despite the availability of good habitat, while others face the ‘problem of plenty’. For instance, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Uttarakhand have reported high tiger population, but Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and all the northeastern states other than Assam have reported very low number of tigers or no tigers at all.

To make matters worse, forests with high tiger density have limited connectivity to other potential tiger habitats due to fragmented corridors, which creates grave challenges for forest managers, conservationists, and people living alongside the tiger.

Consider the case of Tadoba Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra that harbours 97 tigers (AITE 2022). Its spillover tiger population has occupied the adjacent forest divisions of Brahmapuri, Chandrapur, and Central Chanda, and the approximate count now is at 150 tigers. With not enough wild prey to naturally sustain them, the animals prey on livestock. In addition, proximity to human habitation has led to a staggering 253 human deaths due to tiger attacks between 2019 and 2024.

2. Habitat manipulation

Project Tiger requires that every core zone of a tiger reserve be an inviolate space for tigers. This has necessitated the eviction of villagers from these areas. These reclaimed areas are manipulated to stop ecological succession. They are maintained as grasslands to ensure that herbivores flourish to eventually feed the hero of the forest—the tiger. This model may have been essential in the initial years of Project Tiger when tiger numbers were low and there was a need to increase the prey base. But even as this practice has led to an increase in tiger numbers in the short term, it has created long-term challenges of escalated human–wildlife negative interactions. Prey species often eat crops along fringe villages. A recent report revealed that the Government of Maharashtra spends approximately INR 150 crore every year as compensation to farmers in lieu of the crop eaten by deer, nilgai, and wild boar.

Sahyadri Tiger Reserve (STR), in the northern Western Ghats region of Maharashtra, did not report any tigers in AITE 2022. With its hilly and dense forest, it is an excellent habitat for gaur, sambar, and barking deer, but was never an optimal habitat for spotted deer. However, the forest department introduced spotted deer to augment the prey base, in the hope that tigers would ‘settle’ in this forest. But spotted deer are gregarious in nature, prolific breeders, and known to become invasive, and they deplete natural vegetation and eat crops, leading to human–wildlife conflict.

In the way efforts have been made to increase the tiger population at STR, efforts are needed to increase the population of the reserve’s wild dogs or dholes. An endangered species, dholes need as much conservation attention as tigers, as their global numbers range between 949 and 2,215 mature individuals. However, although STR is a paradise for biodiversity, the success metrics only consider tiger numbers.

It is important to understand that STR’s ecological value does not come from tigers alone—it is as much due to the presence of 26 other mammals and hundreds of other faunal species, including the Great Pied Hornbill, Maharashtra golden-backed frog, and 66 species of reptiles and amphibians, all of which contribute to the significance of its biodiversity.

Conservation needs a biodiversity approach

Rather than focusing on increasing the population of a few flagship species, we need to pay attention to preserving biodiversity and helping ecosystems thrive. No species can survive in isolation; it needs every element in its natural ecosystem to flourish in the long term. And so, conservation must take the long and broad view and attempt the following:

1. Look beyond the forest

India has diverse habitat profiles that include grasslands, scrublands, wetlands, and deserts—collectively called open natural ecosystems (ONEs)—where charismatic species such as tigers may not exist, but other important plant and animal groups do. Some of them, like the Great Indian Bustard (GIB) and the Lesser Florican, are critically endangered despite having their own conservation programmes. Instead of considering grasslands as vital ecosystems inhabited by unique wildlife, government records often classify them as revenue wastelands and make them available to industry and infrastructure. This error of judgement has negatively impacted our lesser-known species to a large extent.

The GIB’s habitat in Gujarat and Rajasthan was compromised by renewable energy projects. GIBs and Lesser Floricans (and several other threatened birds such as vultures, eagles, cranes, and flamingos) have died due to collision with power lines laid over ONEs. When we deprive wildlife of their habitat by installing such infrastructure, we create impediments in their natural movement, impact their breeding habits, and threaten their very existence. The GIB, which is the subject of a captive breeding programme, will eventually have to be released into the wild to prevent its extinction, but how will this happen if it has no safe habitat left anywhere that is free of overhead power lines?

Often such ‘wastelands’ are given over to industries for compensatory afforestation projects. The conversion of ONEs into plantations of exotic and fast-growing species with zero native biodiversity conservation value is another form of greenwashing. The sole purpose of such plantations is to sequester carbon and earn carbon credits. However, the rationale that trees are more effective at sequestering carbon than naturally occurring grasses is backed by perception and not by science, as many studies show that grasslands are more reliable carbon sink than forest trees.

2. Look beyond flagship species

In the last 20 years, several new species of plants, arachnids, fish, insects, reptiles, and amphibians have been discovered in the Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. If these species had been considered equally significant as the tiger, the Western Ghats would have immediately been notified as an ecologically sensitive area. But the policy to award it this classification has been stalled for more than 12 years. The subsequent lack of legal protection has opened the door for unsustainable infrastructural development and exotic species plantations in the region.

Left unprotected, the species that inhabit fragile ecosystems are threatened, either directly through the destruction of their habitats or indirectly through factors such as upstream sewage contamination. Climate change has made the survival of niche species even more precarious. For instance, the slightest change in the micro-climate and composition of streams inhabited by the dancing frog will affect its feeding and breeding behaviour. The dancing frog, endemic to the Western Ghats, is one of the most threatened amphibians of India. Yet, shockingly enough, it does not find a place in the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2022. This also holds true for the Schistura hiranyakeshi, a freshwater fish endemic to Amboli in Maharashtra.

An example of the complete disregard for the protection of lesser-known species is the INR 80,000 crore infrastructure project planned in the Great Nicobar Island. The island is part of Sundaland, one of India’s four biodiversity hotspots and home to several indigenous tribes. The project will destroy important parts of the Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve (including 130 sq km of tropical rainforest) that harbours vulnerable species such as the Nicobar scrubfowl and leatherback turtle; endangered species such as the Southeast Asian box turtle and Nicobar treeshrew; and several other rare species, including the Andaman water monitor, that inhabit this island.

When conservation starts focusing on different species, it begins to pay heed to their habitats and food sources. When it looks to protect the caracal, for instance, one of the rarest small cats of India, it will make efforts to secure both its prey base and habitat. The same approach adopted across species will draw more and more habitats and species into conservation focus.

A butterfly survey, for example, would indicate whether certain butterfly species have declined, and this in turn may reveal changes in the area’s floral diversity. In a significant move to address this gap, the Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Uttarakhand forest departments have started bird and butterfly counts in notable tiger reserves. Such surveys need to be long-term and their findings should guide the states’ wildlife conservation plans.

3. Look beyond protected areas

The notion that conservation should only be concerned with species within the protected area (PA) network is flawed. India’s 1,000-odd PAs cover just approximately 6 percent of the country’s geographical area. We need to protect ecosystems that are outside the purview of the PA network (such as wetlands and ONEs) as well. India has fared poorly in protecting its wetlands. ISRO estimated there were approximately 7.5 lakh wetlands (covering 1,52,60,572ha) in India in its National Wetlands Atlas of 2013, but the Wetlands of India Portal, developed between 2018 and 2023 by the Ministry of Environment, Climate and Forest Change, lists only 1,308 wetlands (covering 40,85,945.99 ha).

Sacred groves, which are among the oldest models of wildlife protection in the country, and often under community stewardship, need protection too. In order to do this, it is important to recognise and respect the traditional role that communities have played in their conservation. Of an estimated 1,00,000–1,50,000 sacred groves in India, only 13,720 have been listed and even fewer are well documented. Many sacred groves have been subject to lopping and conversion to green lands by planting exotic species along their fringes.

A more sustainable approach would seek to actively co-opt communities in conservation models by providing them with livelihood opportunities and developing schemes that would make them custodians of natural areas and boost the economy. In places where livelihood opportunities are scarce, nature-based tourism could help make conservation appealing and remunerative. The Amur falcon conservation campaign in Nagaland is a successful example of community-based conservation. Initiated by wildlife conservation organisations to prevent poaching and promote birding, the campaign worked with Naga tribes in building homestays and basic tourism infrastructure and training villagers as tour guides. The campaign resulted in a dramatic decline in poaching of the migrant bird for sport and food.

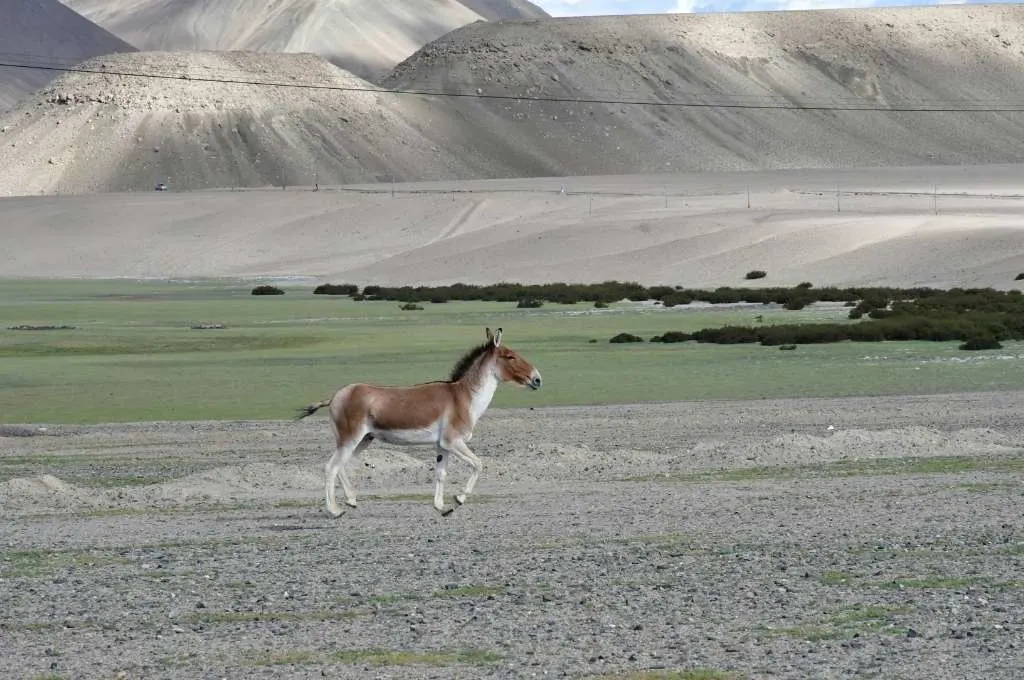

India should not just be applauded for possessing the biggest tiger population (75 percent) in the world, but also for the variety of ecosystems and species it protects. It’s high time we reassessed our approach to conservation. The GIB, grey wolf, Tibetan gazelle, Tibetan antelope, dugong, vultures, flying squirrels, serow, manta ray, dolphins, sea turtles, and thousands of other species occupying the different ecosystems of India are in dire need of conservation attention and support from the government and the private sector. Wildlife is tremendously resilient and needs only a safe environment to thrive. Conservation would serve it well by simply protecting what remains of India’s natural wealth today.

—

Know more

- Read more about why microbes need conservation in India.

- Learn about the impact of tree transplantation on local biodiversity.

- Learn how removal of one invasive species can restore the ecological balance of a forest.