On July 11th, World Population Day 2021, the Chief Minister of the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) released the draft Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilization and Welfare) Bill, 2021. This policy will implement dire disincentives—that violate the right of men and women to realise their fertility preferences—for those who opt for more than two children.

Incentives such as increments, subsidies in the purchase of land, cash incentives for sterilisation, and even maternity or paternity leave for 12 months are advocated. Disincentives include bans on government employment and promotions, ineligibility from “contesting elections to the local authority or any body of the local self-government”, bans on the right to access benefits such as government-sponsored welfare schemes, and even limiting ration card units to just four persons. The policy does call for health-promoting measures as well, but these are essentially a reiteration of currently available services: Maternity centres, supply of non-terminal contraceptives and iron and folic acid tablets, immunisation, contraceptive awareness-raising, promoting spousal communication, and engaging men. However, the rationale for the policy is unambiguously to “control and stabilise the population to promote sustainable development with more equitable distribution”, although the chief minister declared that it would also “bring the path of happiness and prosperity in the life of every citizen”.

Significant strides have been made in India, and also in UP, that contradict the need for some of the policy measures that are being advocated.

It is ironic that this policy has been released at a time when the demographic climate in India is considerably optimistic. Indeed, over the years, the policy and programme environment in India has shifted from a narrow focus on family planning—with incentives, disincentives, and targets—to a broader orientation that stresses sexual and reproductive health and the exercise of rights. Significant strides have been made in India, and also in UP, that contradict the need for some of the policy measures that are being advocated.

In UP, the total fertility rate (TFR)1 underwent a steep decline over the last decade (2005-06 to 2015-16) although it had not reached replacement levels.2 Its age structure places it in the enviable position of being able to reap the demographic dividend, ie. the achievement of a favourable age structure in which the share of the working-age population (15-64) is larger than the non-working-age share of the population (0-14 and 65+). This enhances the potential for economic growth. Maternal, infant, and neonatal mortality have declined, child marriage has declined steeply, and contraceptive use, antenatal care, and skilled attendance at delivery have increased.

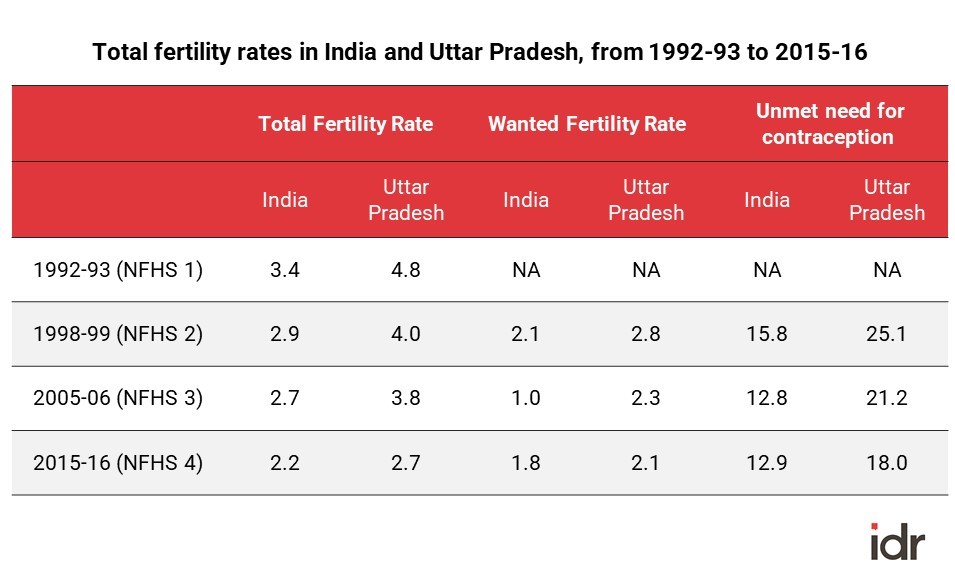

It is true that the TFR has not fallen below replacement levels in 2015-16 in UP (as it has in many other states). Nonetheless, the draconian measures advocated by the state need to be tempered by a perusal of data from the National Family and Health Surveys from the early 1990s to 2015-16. The table below shows several interesting comparisons between India as a whole and the state of UP, which has always had higher fertility levels than the national average. What is notable is that over the period from 1992-93 to 2015-16 (the most recent NFHS findings available), India’s TFR declined by 35 percent, whereas UP’s declined far more rapidly—by 44 percent. And over the last decade, while India’s TFR declined by 19 percent, UP’s declined by 29 percent. Moreover, there is no reason to believe that this trend will not continue, given ample evidence globally that once a sustained decline in fertility takes place, it is rarely reversed even with generous incentives.

Before applying punitive population control measures, UP may want to introspect about its government’s failure to provide contraception to those who genuinely desire to stop or delay childbearing. Two indicators are pertinent because they reflect, to a large extent, the ability of the state to provide contraceptive services and related counselling to women and men. The wanted fertility rate—roughly, the TFR that would have been achieved if women had the number of births they wanted—fell from 2.1 to 1.8 in India for the period 1998-99 to 2015-16. In UP it fell more steeply, from 2.8 to 2.1.

The UP government must introspect about the failure of its programmes to meet the service delivery needs of its population.

The second indicator is the unmet need for contraception—roughly the percentage of women who wanted to limit or space childbearing but were unable to do so. India brought down unmet need for contraception from 16 percent to 13 percent over the 15 years between 1998-99 and 2015-16, while UP brought it down from 25 percent to 18 percent. Even in 2015-16, as many as one in six married women could not access contraception and was at risk of an unintended pregnancy.

Both indicators show that the desire for lower fertility has spread sharply in UP. But the large gap between actual and wanted TFR and the large proportion of women in need who were not served suggest that the state may be lagging in terms of supporting women in meeting their contraceptive goals. From this perspective, the UP government must introspect about the failure of its programmes to meet the service delivery needs of its population, and not resort to a carrot and stick approach that penalises people who cannot access means of contraception.

India is committed to ensuring the reproductive rights of its population, and this includes the right to decide freely whether, when, and how many children to have. It is one of 179 countries that unanimously adopted the ICPD Programme of Action. Indeed the National Population Policy (2000) “affirms the commitment of government towards voluntary and informed choice and consent of citizens while availing of reproductive health care services, and continuation of the target free approach in administering family planning services”. Meeting the contraceptive needs of the population must recognise the kinds of barriers women face in acquiring wanted contraceptive services, and adapt service delivery to meet these needs. For example, limited freedom of movement inhibits many women from accessing health centres and other outlets for contraceptive methods. Programmes must ensure that a basket of methods becomes available to them in the home environment. For many, sterilisation may be an unattractive option, making the availability of a range of non-terminal methods essential.

Imposing drastic disincentives on those with more than two children clearly targets the most disadvantaged.

Finally, the myth that newly married young couples would not wish to delay their first pregnancy must be busted. Many newly married couples do wish to do so but don’t have access to the necessary counselling and supplies, because health care workers do not approach them until they are already pregnant. Modifications of the service delivery system to accommodate these lapses are far more likely to be effective than imposing punitive laws.

Issues of equity also come into play. Imposing drastic disincentives on those with more than two children clearly targets the most disadvantaged—the poor, the malnourished, the poorly educated, and those at greatest risk of maternal, infant and child mortality. Denying them schooling benefits, rations, employment opportunities, and more ensures that they remain most disadvantaged.

A draconian policy that violates citizen’s rights will never result in “bring[ing] the path of happiness and prosperity in the life of every citizen”. It is the state’s duty to fulfil the rights to which all its citizens are entitled in order to ensure their happiness and prosperity.

—

Footnotes:

- The total fertility rate in a given year is a hypothetical measure reflecting the total number of children a woman would have if she were to experience by the end of her reproductive years the number of births experienced today by each five-year age cohort from age 15-19 to 45-49 (known as age specific fertility rates).

- Replacement level fertility refers to a total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1 children. It implies that each couple is having just the number of children to replace themselves. Over time, if sustained, this implies that each generation will exactly replace itself.

—

Know more

- Learn more about reactions to UP’s proposed population bill.

Do more

- Modifications, suggestions, and other ideas to the draft Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilization and Welfare) Bill, 2021 can be emailed to statelawcommission2018@gmail.com by July 19th, 2021.