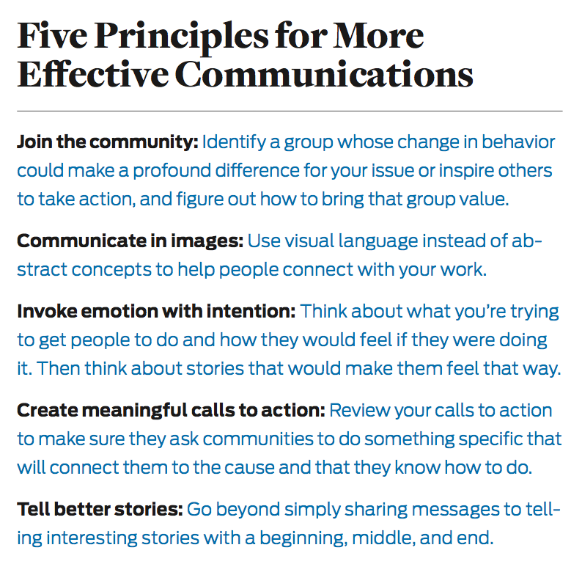

In what follows, we delve into the science behind what makes people care. We’ve identified five principles that are supported by research from a range of academic disciplines. Collectively, these rules offer a framework for building and assessing your communication strategy and designing efforts more likely to result in belief and behavior change. But, as with any effort to apply research findings to strategy, we have to be cautious not to overstate or oversimplify what the research tells us.

Perhaps most important, applying these principles doesn’t require you to make a massive investment in new communications efforts. Rather, they offer a way to make the work you’re already doing more effective. Since they are also easily mastered, people throughout your organization can embrace their roles as communicators regardless of their title or role.

Related article: Communications 101: Talking about your nonprofit

Principle #1: Join the community

Research from multiple disciplines tells us that people engage and consume information that affirms their identities and aligns with their deeply held values and worldview, and avoid or reject information that challenges or threatens them.[1] This requires advocates to move beyond a focus on building and disseminating a message to stepping into the world of their target community.

[quote]If we want people to engage and take action, we have to connect to what they care about and how they see themselves.[/quote]Think of communication less as a megaphone and more as a gift to your audience. Does it help them solve a problem? Does it make them feel good about themselves or see themselves as they want to be seen? Does it connect to how they see the world and provide solutions that are actionable? If we want people to engage and take action, we have to connect to what they care about and how they see themselves.

How to apply this insight: Identify a group whose change in behavior could make a profound difference for your issue or inspire others to take action, and figure out how to bring that group value.

Principle #2: Communicate in images

People in the social sector work on complex issues that are fairly abstract: justice, equality, wellness, fairness, and innovation. One of the challenges with these abstract concepts is that they leave space for people to make assumptions about what these terms mean to them. For example, someone hearing the term “innovation” might worry about how innovations in tech could make their job unnecessary, while another might interpret it as a way to apply fresh thinking to stubborn challenges.

But concrete, visual language engages the visual and emotional areas of our brains. “For us to go from ‘I think I understand’ to ‘I understand,’ we need to see the sights and feel the motions. Many experiments have shown that readers understand and remember material far better when it is expressed in concrete language that allows them to form visual images.”

How to apply this insight: Try creating a picture in the mind of your audience of what that concept looks like. Use visual language to help people connect with your work. The next time you write a presentation for yourself or someone else, try printing it out with wide margins. Can you create drawings of the images you’re creating in your listeners’ minds? If not, go back and add visual language that will keep their attention and stick in their memories.

Courtesy: SSIR

Principle #3: Invoke emotion with intention

People who work for social change want others to feel as strongly as they do about their cause. And most of us recognize the importance of telling stories that invoke profound emotion.

Communications strategists know they have to be deliberate in identifying their goals and target community. We have to use the same intention with the emotions we choose to invoke. Each emotion can lead people to different actions, and pleasant emotions can be especially effective. As you think about what it is you want people to believe and do, use emotion with intention.

How to apply this insight: Think about what you’re trying to get people to do and how they would feel if they were doing it. Then think about stories that would make them feel that way.

Principle #4: Create meaningful calls to action

“Sign our petition.” “Follow us on Facebook.” “Click here for more information.” Do these calls to action sound familiar? As common as they are, they don’t tell anyone how to make a difference. They may leave people feeling like their efforts will be mere drops in a bucket. They don’t inspire.

[quote]Review your calls to action. Ask communities to do something specific that they value, that will connect them to the cause, and that they know how to do.[/quote]So how do we create calls to action that motivate people to take action and will make substantial progress toward our goal? Effective calls to action follow three rules: They are specific; the target community sees how the solution will help solve the problem; and they are something the community knows how to do.

How to apply this insight: Review your calls to action. Are you asking communities to do something specific that they value, that will connect them to the cause, and that they know how to do?

Related article: If a report is published and no one reads it, did it really happen?

Principle #5: Tell better stories

While the social sector has embraced the importance of storytelling, many people are not actually sharing stories. Instead, they use vignettes or messages. Stories have characters; a beginning, middle, and end; plot, conflict, and resolution. If you do not include these elements, you are not telling a story.

As people hear a story, they seek cues about how the story will unfold and who the protagonist is. Familiar plot structures—such as “rags to riches” (“Cinderella”)—help orient the audience’s expectations about the events to unfold and whose team they should be on. This is particularly important for communicating with audiences that may not be familiar with the issue you are working on. But for audiences that are very familiar with the issue, playing with plot structures that break expectations and surprise them may be more important for capturing their attention and avoiding fatigue from hearing the same story one too many times.

Illustration by Shonagh Rae | Courtesy: SSIR

But simply using these different plots doesn’t guarantee that people will engage with the tale you want to tell. Organizations that have adopted a strategy of incorporating stories in their work frequently reuse the same plot structures, emotions, and types of characters. As a result, many organizations tell stories that just aren’t that interesting. Gain your community’s attention and engagement with unexpected twists, less-used plot structures, and unusual characters.

How to apply this insight: Are you telling stories with a beginning, middle, and end, or simply sharing messages? What new insights will your audiences gain from hearing these stories? Are your stories interesting enough in their own right to merit a listen—even if the listener isn’t passionate about your issue? And are you using the empty and full spaces of your stories to help people gain new insights on topics and issues they assume they know well?

A new perspective

If you’re finding that your communications strategies aren’t working, consider this: People fail to act not because they do not have enough information, but because they don’t care or they don’t know what to do. If you start with this perspective as the foundation for your work, you can craft a strategy that helps people care and tells them exactly what you want them to do.

This is an edited excerpt from an article that was originally published on Stanford Social Innovation Review. You can read the original here.

[1]Gregory S. Berns et al., “Short- and Long-Term Effects of a Novel on Connectivity in the Brain,” Brain Connectivity, vol. 3, no. 6, 2013, pp. 590-600. Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, New York: Vintage, 2012. Matthew Feinberg and Robb Willer, “From Gulf to Bridge: When Do Moral Arguments Facilitate Political Influence?” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 12, 2015, pp. 1665-1681. Dan M. Kahan, “Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection,” Judgment and Decision Making, vol. 8, no. 4, 2013, pp. 407-424.