Educators debate few topics as hotly as Education Technology, also known as EdTech. Proponents, such as The Economist, argue that “technology can make big improvements to education (because) teachers are often unqualified, ignorant or absent; tablets show up and work.” Critics, such as Paul Skidmore of Rising Academies, caution that EdTech’s track record is “pretty dismal,” particularly in low-income settings.

Our report on EdTech in India, produced by the Central Square Foundation, found that EdTech’s proponents and critics are both, in part, right. The report synthesized results from process evaluations conducted on a dozen Indian EdTech products. The evaluations used surveys and interviews of 1,500 students, teachers, headmasters, and parents in ten states as well as product use data from tens of thousands of students, teachers, and schools across the country.

Overall, we found that EdTech has significant potential to increase student learning levels. The market seems to agree, and the sector is booming. Yet several challenges stand in the way of the EdTech revolution. First, EdTech product quality varies greatly yet is hard to observe, making it difficult for schools and administrators to choose an appropriate product. Second, few products are designed with the needs of low-income students in mind. Third, implementing EdTech well requires effective monitoring and support systems, which many school systems are unable to provide.

Researchers, funders, and implementers can capitalize on the EdTech investment boom by pushing the sector to stay focused on student learning and not ignore low-income students. Researchers should further study pedagogic approaches and implementation strategies. Funders should support research and invest in products that serve the low- and middle-income segments. In the meantime, schools and governments interested in EdTech should proceed carefully. Before deciding to use EdTech, they should ensure that they are able to select a high quality product and effectively support and monitor its use.

Existing research and trends

Recent evaluations of EdTech interventions in low- and middle-income countries show that, like most tools, the impact of using EdTech is highly context, product, and implementation dependent. Some past EdTech interventions have increased learning outcomes. A few increased learning dramatically. 1 Positive outcomes have not been limited to only wealthy or well-prepared students. 2 However, studies have also shown mediocre and, in a few instances, even negative effects. 3

The mere provision of computers or other technology is unlikely to raise learning levels.

Two general trends emerge from these studies. First, mere provision of computers or other technology is unlikely to raise learning levels. 4 Second, in India, products that match instruction to student learning levels can be highly effective. This is likely due to the high heterogeneity of student learning levels in the same class. 5

Regardless of the research, the private sector clearly believes that EdTech can work, at least as a business model. Investment in EdTech in recent years has surged, reaching billions of dollars in China and nearly that in India. Most of this investment in India has gone towards products targeting high-income consumers.

Findings from process evaluations

As part of Central Square Foundation’s EdTech Lab initiative, we ran rapid process evaluations on twelve Indian EdTech products. The primary objective of the evaluations was to determine which products were the best candidates for scale-up. However, several general findings came out of these evaluations.

Most of the EdTech products were not designed well for low-income students. While a few products worked well for these students, many had major gaps in their design.

We found that most of the EdTech products were not designed well for low-income students. While a few products worked well for these students, many had major gaps in their design. For example, few products had quality vernacular language navigation or content, a critical feature given limited English proficiency among low-income students. Several products used Western names, references, and accents that confused students. Many devoted fewer resources to foundational content, an area where many students fall behind. Few products adequately matched instruction levels to student learning levels, an important feature for students learning at different levels within the same classrooms.

We found product quality varied tremendously and was hard to assess without using structured tools. We evaluated product quality on five criteria, such as product design, student engagement, and the ease of adoption. We conducted interviews with teachers and students, used products’ own back-end MIS data, and directly observed the product being used. Performance on these criteria varied enormously and was not correlated with product type, feature set, or other easily observable characteristics.

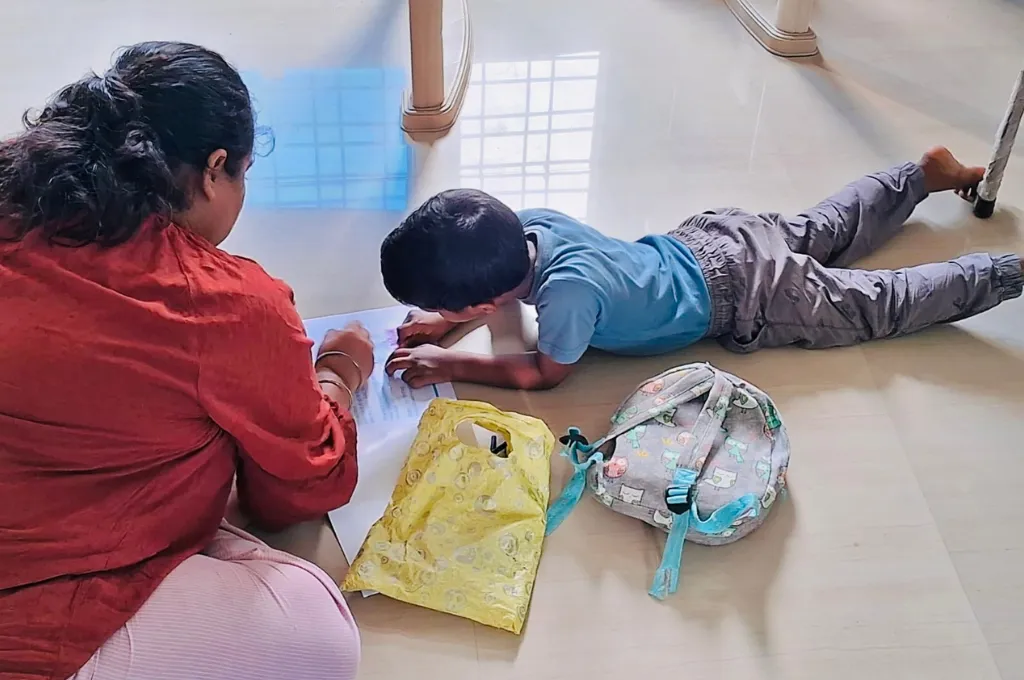

Few products adequately matched instruction levels to student learning levels, an important feature for students learning at different levels within the same classrooms. | Picture courtesy: Ajaya Behera/Gram Vikas

We found that practitioners had difficulty effectively implementing products. Part of EdTech’s appeal is that it promises to be a quick fix to a wicked hard 6 problem. Unsurprisingly, that was not the case. Many schools had trouble consistently using products. Some teachers across product and implementation models needed regular, sometimes daily, support with tasks as simple as start-up and basic navigation. Further, the usefulness of the products, like many other inputs into schooling, depended on the ‘coherence’ 7 of the system.

Using the RISE framework, the most common issues we found were incoherence between the delegation and information elements of the management accountability relationship. More simply put, administrators asked teachers to help children learn but measured teachers’ success using information that could (unintentionally) work against that goal. For example, some teachers said they were reluctant to use products that deviated from the curriculum, even if the products appeared helpful to achieving learning outcomes, because they were held accountable to completing the curriculum.

Despite these challenges, we observed several instances where EdTech products appeared to be working well. In many cases, EdTech content was at an appropriate level (and sometimes even tailored to individual student needs, though not as often as product makers claim) 8 and the product was consistently used in the way intended. While EdTech use can sometimes be a burden to teachers, especially if it’s hard to use or does not help them progress through the syllabus, in some cases it appeared to lighten their load. And while teachers mainly stuck to videos, ignoring products’ more advanced features like lesson plans and activities, some research shows that high-quality videos alone can improve learning.

Recommendations for researchers, funders, and implementers

Researchers can help EdTech realize its potential by exploring how to best design, select, and implement EdTech products. We know little about which pedagogic features are most important. We also know little about how best to implement EdTech products at scale in government schools. CSF’s EdTech Lab and a Global Innovation Fund and J-PAL collaboration are making important progress on these questions.

For funders, we believe that the enormous investment in EdTech creates a huge opportunity for social impact if these resources can be directed well. Funders could help by funding research on designing, selecting, and implementing EdTech. They could also push more EdTech product makers to target lower income segments. This would likely require targeted grants or credible purchasing commitments. Further, they could help implementers study and improve how their products are working in practice, a big need given the difficulty of assessing quality.

For governments or school systems seeking to implement EdTech, the findings suggest caution. We find that product quality is hard to assess, and that implementation is difficult to do well. These are both big problems. Governments tend to be struggle with procuring software when quality is not easily observable. Getting implementation right and creating coherence in sclerotic government education systems can be difficult. Before sinking a lot of money into EdTech hardware, governments should be confident that they have a procurement system which can weed out the winners from the losers, and that they have sufficiently piloted and refined the training, support, and accountability systems needed for the products to improve student learning.

This piece was originally posted on the RISE website on 14 January 2020 and is one of a series of articles from RISE—the large-scale education systems research programme supported by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

- See, for example, Banerjee et al. (2007); Carillo et al (2010); Muralidharan et al (2019); and Beg et al (2019).

- See, for example, Beg et al. (2019) and a forthcoming paper by Karthik Muralidharan on schools in Rajasthan.

- For example, Linden (2008) finds large negative effects from an EdTech intervention.

- See Online Appendix C in Muralidharan et al (2019).

- See Banerjee, et al. (2017), Carillo et al (2011), and Muralidharan et al (2019).

- Definition from Andrews, Pritchett, Samji, and Woolcock: “Simultaneously logistically complex, politically contentious […], have no known solution prior to starting, and contain numerous opportunities for professional discretion.”

- We interpret ‘coherence’ as alignment of the accountability relationships between actors in the system around a common objective, which should be student learning.

- By analyzing product data on usage patterns and content delivery we were able to see that some products which claimed to be ‘personalized’ or ‘adaptive’ did not, in fact, tailor their content to student needs.