Corporate and private wealth are becoming the new drivers of development in India. Given the volume of money at their disposal, they are increasingly shaping development decisions and resource allocations.

It is therefore important, both for the funders as well as the social sector at large, that this money is used effectively—that the focus is on bringing about real change in the lives of millions of Indians rather than merely ‘reaching’ that many people.

The profile of new money

The new money that has been finding its way into the social sector in recent times comes from various entities and is varied in terms of intent and potential.

- Philanthropy: Philanthropic funding from private individuals is estimated to have increased from approximately INR 6,000 crore in 2011 to around INR 36,000 crore in 2016, which is almost twice the net overseas development assistance of approximately USD 3.2 billion to India in 2015. In effect, private donations made up 32 percent of total contributions to the development sector in 2016, up from a mere 15 percent in 2011

- Corporates: Corporate social responsibility (CSR) spend for the top 100 companies in India was INR 10,000 crore in 2016.

- Impact investment: The cumulative investment in social enterprises in India has been INR 33,500 crore since 2010. McKinsey &Company believes impact investments have the potential to grow 20-25 percent a year between now and 2025, reaching INR 38,500 crore.

- Intermediaries: Several multilateral, bilateral and international foundations have also started supporting platforms like Dasra, Samhita and Give India, which leverage these new funds to achieve a multiplier effect.

Look beyond reach, understand impact

Given their experience and expertise, the new players have brought lean monitoring approaches from the corporate world to the social sector. This has strengthened the monitoring of project-specific outreach and immediate results, such as people reached, children enrolled in school, health workers trained, and so on.

However, if we are to achieve our Sustainable Development Goals, these funders must make sure they invest in programmes that go beyond just the outreach numbers and actually improve the lives of the poor and marginalised in our country.

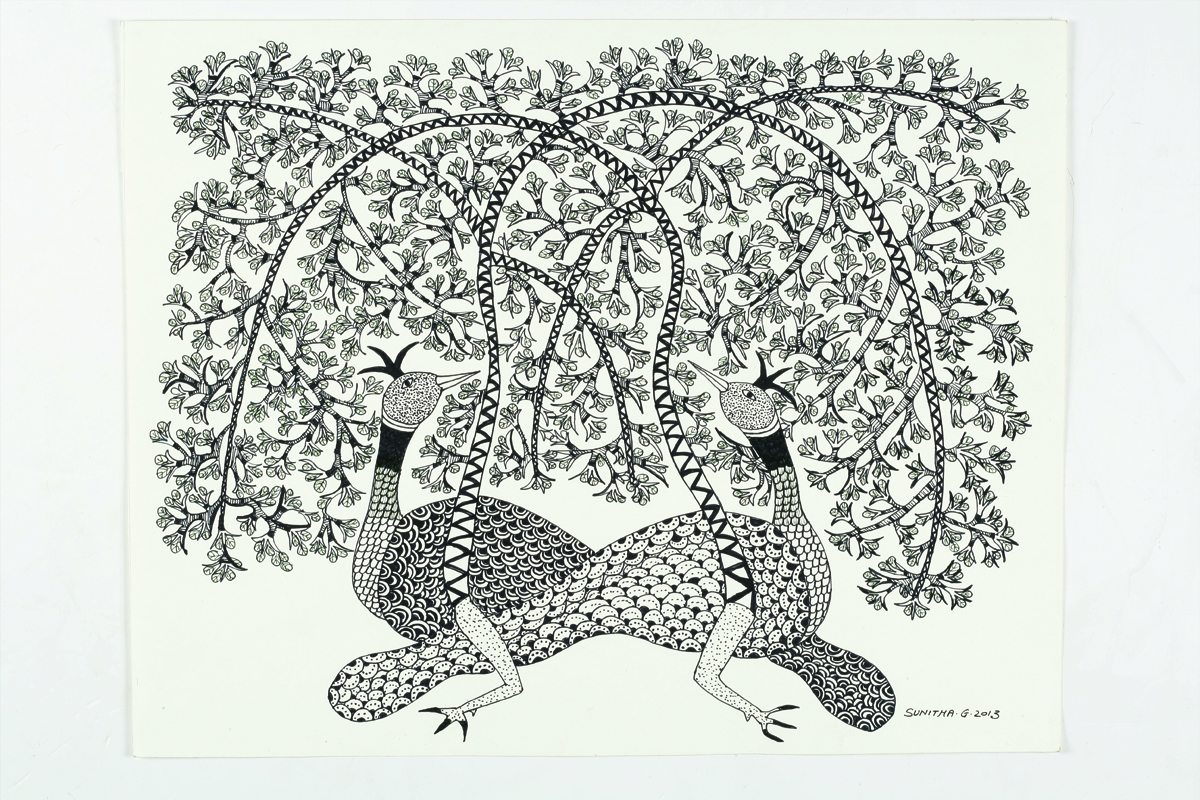

Image Courtesy: Aseema Charitable Trust

Use evidence to make funding decisions

For this to happen, CSR, philanthropy, impact investing and intermediaries must strategically invest in using and building evidence on the programmes they support in the following four ways:

Related article: How to use data to improve decision-making

1. Use evidence that has already been generated to identify interventions

Systematic reviews and evidence gap maps are both types of evidence that are public goods, which means they are widely available for use and can help funders understand the impact of the interventions being considered for investment.

a) Systematic reviews

- What are they? Systematic reviews are rigorous literature reviews that gather and analyse multiple studies on the impact of an intervention.

- Who does them? 3ie and Campbell Collaboration are good sources for both these kinds of evidence.

- What do they look like? A great example of a systematic review is this one on education, which concluded that different approaches should be used to support attendance (e.g. cash transfers) and learning (e.g. improved pedagogy). The rigorous nature of this review makes it one that helped inform this year’s World Development Report.

b) Evidence gap maps (EGMs)

- What are they? EGMs consolidate what we know and do not know about what works in a particular sector or sub-sector by mapping completed and ongoing systematic reviews and impact evaluations in that sector.

- Who does them? They are being carried out by organisations like 3ie, the International Rescue Committee and UNICEF.

- What do they look like? An example of an EGM is this one on interventions to improve state-society relations, which collected rigorous evidence on the role of the state, the effectiveness of state institutions and state legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens in low- and middle-income countries. The study was commissioned and is being used by USAID in informing programming.

2. Set aside approximately 10 percent of the investment for evaluation.

While monitoring money allows the grantee organisation to build an MIS for tracking their immediate results, it is also important for the funder to commission evaluations for understanding the impact and cost effectiveness of their projects.

a) Types of evaluations: There are different types of evaluations available depending on the questions that need to be answered. Some examples are:

- Impact evaluations answer the question, “Does the programme work (what difference does it make to outcomes and impacts, and for whom)?”

- Economic evaluations tell us whether the effects of an intervention are worth its costs.

- Process evaluations tell us how, why and under what conditions the programme works.

- Formative evaluations help us understand how to improve the project for the context in which it is to be implemented.

b) Who does them? Agencies that funders can use include 3ie, J-PAL, Oxford Policy Management, Indian Institute of Human Settlements and Population Council.

To ensure that this 10 percent is used effectively, funders must go beyond logic and results frameworks. They must insist that proposals include theory of change, monitoring and evaluation plans, the strategy to use the evidence generated, as well as details around senior M&E talent at the organisation.

3. Ensure that the evidence generated through the project is used for the organisation as a whole.

Insights generated through evaluation are useful not only for project-related decision making but also for organisation-level strategic planning, advocacy and fundraising.

To this end, implementers can develop dashboards, score cards and policy briefs based on their monitoring and evaluation results, and build platforms to discuss their implications for policy and programming.

This ensures the organisation becomes more robust and sustainable over the longer term, which is an important factor that funders like to consider.

The risks of not investing in evidence

Longstanding development funders like the Government of India, USAID, DFID, the World Bank and UN agencies (and a few new ones like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) have invested in building evidence on the impact of their funding and are using this to drive future investments.

If the new development players do not take these measures, they run the risk of wasting their resources on projects that do not change people’s lives for the better or ones that are not scalable. Even if their projects do have an impact, they will lack any robust evidence to demonstrate that. This further curtails organisations’ ability to advocate for scale and influence policy, which ultimately gets in the way of the sustainability of not just the organisation but also the impact on the people reached.

*The artwork above is courtesy of the nonprofit Aseema. For more information, please click here.