Among development initiatives aiming to boost both healthcare access and women’s income empowerment, using female sales agents to sell health-related products is sometimes seen as a panacea that can achieve both goals at once. The approach is believed to enhance women consumers’ access to health-related products, due to the sales agents’ strong networks and ability to connect with women customers and relate to their needs. As these agents sell essential products to their peers, they help to promote behavior change around health. Furthermore, the women who work as sales agents earn an income, which is assumed to lead to greater economic independence.

However, little research has been done to prove or disprove these beliefs.

With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Hystra recently analyzed the data and best practices of 21 organizations that rely principally on women direct sales forces to sell health-related products, to understand whether these assumptions held true. We’ll present some of our results and share the experiences of several of these organizations below, discussing the conditions necessary for women sales forces to be a cost-effective choice, assessing the income created for sales agents, and sharing a few best practices that can help attract and retain women agents.

A lack of data on women sales agents’ real impact

One challenge when trying to assess the effectiveness of this approach is the fact that little data is available on the real impact of women sales forces on consumers, and even less on their impact on agents themselves.

While NGOs usually measure the impact of their activities on their consumers’ health annually or for specific development programs, commercial organizations selling health-related products very rarely measure their impact on consumers. The consumption frequency of products could act as a proxy for impact, but it was only measured by three organizations in our sample.

When it comes to the impact of these organizations on women agents themselves, the only commonly available data point is women agents’ income, which we hence used in this analysis as a proxy for business and social impact.

The conditions for women sales agents to sell well

We found that women sales forces are well-suited to sell health-related products in contexts where working with women brings a competitive advantage.

It’s important to recognize that women’s employment opportunities in developing countries are still highly limited by mobility.

More fundamentally, we found that for women to work in direct sales forces, their work must first be possible in that context. While that may seem obvious, it’s important to recognize that women’s employment opportunities in developing countries are still highly limited by mobility, and thus they can mostly occupy sales positions that require little or no traveling.

When they can work, women are generally more effective than their male sales force counterparts when selling products targeting women or children–and in particular products related to cultural taboos such as menstrual hygiene and family planning. Nutri’zaza, a social business fighting children’s malnutrition through fortified porridge in Madagascar, observed the impact of women agents’ credibility for child-related matters. The company, 91% of whose sales agents are women, found that it took male door-to-door sales agents four times longer on average to create a targeted customer base than it took women agents.

Women agents can also be more cost-efficient than a male salesforce for work that requires part-time commitment: this work is better suited to women’s needs and constraints (in particular household responsibilities, which still overwhelmingly fall on women’s shoulders), while men would rather look for full-time jobs with higher earning potential. The availability of pre-existing local female networks—in places without a male equivalent—can also make it easier, and thus cheaper, to find qualified women than men. That was the experience of Frontier Markets, a social e-commerce platform working with 10,000 women sales agents to serve rural customers in India. The company works with NGOs to recruit potential agents through local Self-Help Groups, whose members are already trained in financial management, have a payment history and are easy to reach through these groups. This makes recruitment more cost-efficient than if they tried to find similarly qualified men.

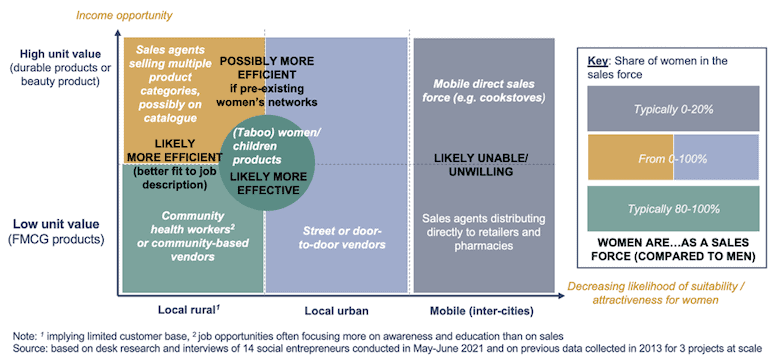

The following graphic summarizes a sales model’s suitability and attractiveness for women based on the mobility required—which makes it easier or more difficult for women to join. It also shows the value and type of products sold—which make it either more or less attractive for men to join too, and thus more or less competitive for women.

As a result of the considerations above, as shown in the bottom left corner of the graphic (in green), organizations selling low-unit value products in rural areas via direct sales typically rely mostly on women sales agents. In contrast, in the right column (in dark grey), organizations requiring their sales agents to travel across villages or cities are typically mostly working with men—only reaching up to 20% women sales agents when they make dedicated efforts to be more gender-balanced. For organizations whose approach falls between these two cases, the choice to work mostly with men or women depends on factors that might make them more cost-efficient—e.g., whether they can access pre-existing networks that can make it easier to recruit sales agents of one gender rather than the other.

Assessing the impact of women sales agents’ income

We found that through these employment opportunities, women can access a marginal to sizeable income. Depending on the density of their catchment area and the unit price of the goods they sell, the average incomes for these women sales agents varied by a factor of 20 across the best-in-class organizations we studied. Incomes tend to be lower in rural areas, where the customer base is more limited due to lower population density. Across the organizations studied, sales agents in rural areas selling health-related fast-moving consumer goods make between $50 and $300 annually ($200 to $700 in Full Time Equivalent [FTE]), which only represents add-on revenue for the household. Agents selling non-gender-specific durable goods in rural areas usually earn more—$300 to $800 annually ($700 to $3,200 FTE), the higher end of which can approach a livable wage in some regions. In urban settings, sales roles have a denser catchment area and provide the possibility of working longer hours, making for more significant income streams ranging from $500 to $4,000 annually ($800 to $4,000 FTE), which is typically higher than local minimum wages for formal employment.

To be successful and sustainable, women sales force models needed to adapt to women agents’ specific needs and preferences.

It is, however, important to remember that some studies demonstrate that for women, earning an income does not automatically translate into “empowerment”—i.e., increased financial control, decision-making and agency in their household. Across the organizations we studied, none had looked deeper into this next level of impact, which typically requires dedicated (external) funding to be measured.

Adapting sales force models to women’s needs

We found that, to be successful and sustainable, women sales force models needed to adapt to women agents’ specific needs and preferences.

To that end, a few clear quick wins emerge in terms of human resource practices that can motivate and retain women in sales force roles. Profiling potential agents well in the hiring process is a first step. We have found that across organizations, the best-performing women agents often shared a similar profile: They have a good reputation within their community, are usually married with children old enough for them to be away from home, are digitally savvy, and (ideally) already have some community or work experience.

Once women are hired, some specific practices can help improve their chances of success when operating in a direct sales force. In many cultural contexts, women first need to get support from their family before joining a sales force, which can be facilitated by the company. For instance, Greenstar, a Pakistani social marketing organization providing access to family planning methods, leverages community elders to help relatives—and husbands in particular—understand the women’s new position as community health workers.

Adapting training to women’s needs, working in particular on increasing self-confidence, has also proven effective. For example, the Clean Cooking Alliance—a global network supporting clean cooking companies—has developed an “Empowered Entrepreneur Training Handbook” specially dedicated to women sales agents. Participants reported a 10% increase in sales, and 91% of them reported a high or very high level of self-esteem after the training, compared to 63% before.

Non-financial incentives that benefit the entire household also seem to motivate women agents’ retention.

To increase sales agent retention and allow them to commit over the long term, many organizations adapt women agents’ work schedules so that they can perform other duties, and/or they adapt agents’ roles to women’s physical capabilities and mobility constraints. For instance, Living Goods allows for flexible work schedules for their over 11,000 Community Health Workers in Uganda and Kenya, to allow them to balance serving clients with household responsibilities. And in Brazil, Danone provides its “Kiteiras” (sales agents) with a catalogue of their dairy products to generate sales, enabling them to visit many homes at once without carrying all the products, and come back later for targeted deliveries.

Additionally, we found that non-financial incentives that benefit the entire household also seem to motivate women agents’ retention. Through the Sharing Cities program, which distributes Bel Group’s dairy products through both male and female street vendors, Bel noticed that health insurance and financial contributions towards children’s education were particularly effective incentives—first to enroll women, and later to limit churn—more so than for men, who favored product promotions.

Female sales forces: an effective solution, but not a panacea

While female sales forces might not be the panacea some had hoped, they can, under the conditions described above, be the best solution to achieve improved access to health and women’s income opportunities. However, organizations considering leveraging women direct sales forces should be realistic about the number of people these women will be able to serve, given their limited mobility—and also about the income they will be able to generate, considering the part-time hours they tend to prefer.

It should also be noted that structural inequalities that constrain women and shape their (often multiple) social burdens are also one of the reasons women seem to be well-suited to the particular roles highlighted in our report, and summarized in this article. Further research is needed to gather more data (beyond income) on the impact of women sales force models, in order to better document the business case for this approach, to clarify its (social) return on investment, and to identify more best practices to maximize its chance of success.

We hope that the insights above—and the overall report—can be a first basis to better understand the role and impact that women sales forces can have, as well as the barriers that prevent them from doing more. Ultimately, we hope to motivate more players to look further into the impact potential of these models, to work on overcoming those barriers, and to focus on bringing women sustainable income opportunities through jobs that can also change lives.

Note: This article is based on research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This article was originally published on Next Billion.