Creating meaningful change is a complex process that requires time, sustained effort, and unravelling deeply rooted systems. True transformation does not occur overnight or even within a single generation—it takes place across generations, shaped by the lived experiences and perceptions of the communities involved. For nonprofits working at the grassroots level, this reality presents a dual challenge: meeting the immediate demands of funders, who often seek measurable outcomes within tight timelines, while staying true to the slower, more organic pace of intergenerational change.

In iPartner India’s experience, addressing change in communities where sex work is a traditional occupation—as in the case of the Nat community—requires patience, perseverance, and a deep understanding of the socio-cultural dynamics at play.

Historically, communities like the Nat have been marginalised and systematically excluded due to colonial policies that stripped them of traditional livelihoods, such as entertaining the local royalty and the public through cultural activities; this forced many into extreme poverty. With limited access to social welfare entitlements, certain families within these communities have relied on sex work as a means of survival across generations.

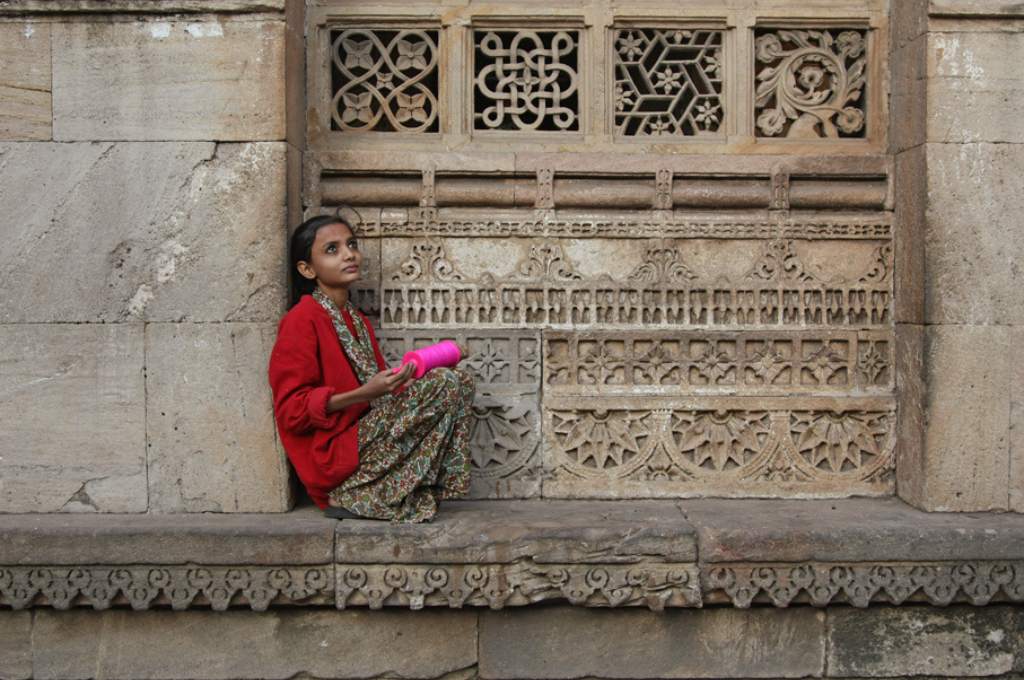

Sex work has been a part of the Nat community’s culture for a long time and is not stigmatised within the community, unlike in mainstream society. On the contrary, it is normalised, which comes with its own problems. The practice is passed down within families and young girls are often initiated by older relatives, limiting their opportunities for education or alternative careers. Additionally, limited access to information on sexual health, legal rights, and financial independence makes it challenging for girls to explore possibilities beyond sex work.

Breaking such entrenched cycles isn’t easy, especially in communities where a family’s economic survival often depends on their daughters entering sex work. Since 2018, we have worked with groups belonging to the Nat community to create alternatives to this practice through a programme called ‘Rakshan’. Our efforts include equipping young girls to make informed choices about their bodies and futures and exposing them to the information and skills needed to pursue education and alternative livelihoods. While we do not want to force anyone out of sex work, we aim to ensure that if they choose to enter the profession upon adulthood, they do so from a position of awareness and self-determination, with knowledge of their health and rights. Our biggest learning is that such changes are intergenerational and take time.

Change happens gradually

The journey to creating change is exactly that—a journey. It is rare for a nonprofit or community-based organisation to intervene in a community on an issue that shows immediate results. For us, preventing young girls from entering sex work and sustainably breaking the cycle requires a multi-pronged strategy that addresses the community at every level.

1. Building trust

Building trust with any community takes a long time, especially with historically stigmatised and marginalised groups. Key challenges include overcoming mistrust towards outsiders, establishing one’s credibility, demonstrating a long-term commitment, and proving genuine intentions to support the community’s well-being.

Members of the Nat community often do not trust outsiders easily due to a fear of being reported to authorities. At times, they distrust our team, refusing to share family data out of concern that we might disclose it, potentially jeopardising their livelihood.

In our experience, building trust has been achieved in a few different ways:

a. Creating safe and open spaces: We have formed groups tailored to different age groups and genders to address their specific needs and perspectives. The first group, called ‘Bal Panchayat’, is for children, where the team meets monthly to discuss their rights, fostering agency and awareness from a young age. The second group, ‘Yuva Mandal’, or youth committee, provides a space for young people to talk about aspirations, education, and future plans—going beyond the confines of community norms. The third group is for women, where they learn about savings, alternative work options, building financial independence, and supporting their daughters. These groups offer safe spaces to explore new beliefs, reflect and relate to one another’s experiences, and cultivate an openness about issues and alternatives.

b. Engaging with community mobilisers: Village-level mobilisers are hired from within the community, which has been transformative. These mobilisers help engage the community and serve as cultural liaisons, helping us understand deep-seated beliefs in the community.

For example, one such belief that we learned about is the notion that girls are the primary breadwinners. Sex work is viewed as a convenient way to generate income, whereas other livelihood options are seen as requiring more time and effort. Concerns about educating girls are tied to both practical and cultural norms: many believe that if girls are educated, their households will struggle to function, as men lack the skills to earn a livelihood.

Furthermore, a mobiliser from within the community can communicate sensitive issues and build relationships with a greater degree of effectiveness than a nonprofit coming from outside. For example, when Savita,* a village-level community mobiliser, learned that Ruchi Madhiwal,* a 13-year-old from Ramjipura village, was being pressured by her aunt—her only guardian and a sex worker herself—to enter sex work, Savita stepped in. Through counselling and consistent support, she built trust with Ruchi’s aunt and convinced her to allow Ruchi to continue her education.

c. Building community capacity and skill: Apart from working with women and girls, including male community members in livelihood activities and skill training is critical for earning their trust. Many men in the community remain unemployed or unmotivated to work, relying on income from female relatives engaged in sex work. Additionally, not sending a girl into sex work is often believed to hinder her brother’s chances of marriage due to the unaffordable bride price. Engaging men addresses broader economic needs and offers alternatives to reduce reliance on income from sex work.

2. Providing long-term solutions and seeing their implementation through

When nonprofits work to address customs, traditions, or entrenched issues within communities, one of the main challenges they sometimes face is finding solutions or alternatives to the behaviours they are seeking to change. It is often not enough to simply point out the problem, especially when working with communities whose livelihoods are affected.

We have been working through the following two solutions, both of which regularly reinforce our need to be patient and internalise that intergenerational change will be slow.

a. Providing alternate livelihoods: Convincing individuals to shift to alternative livelihoods often means taking them away from something stable, albeit exploitative. One of the significant challenges we face is the income disparity between earnings from sex work and other available occupations—the difference can be almost between INR 30,000 to 50,000 per month, depending upon the age of the girls who have been trafficked as well as other factors.

Goat and poultry farming have emerged as viable livelihood options. However, with a one- to two-year gestation period, sustained support is needed to stabilise these alternatives and reduce reliance on young girls supporting families through sex work. One of our key learnings through this process is that introducing and proving the efficacy of alternative sources of income is not immediate. It takes time to develop skills and establish sustainable income streams.

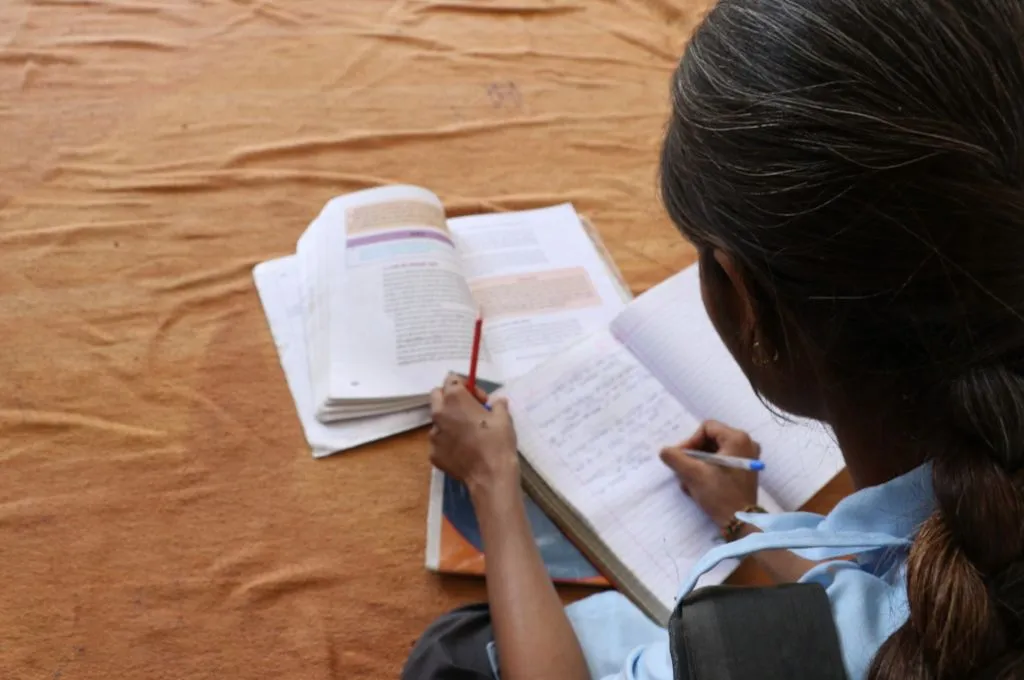

b. Encouraging education: Since many marginalised communities have not experienced the benefits of education for many reasons, including historical barriers to accessing quality education, creating such a culture requires sustained commitment and it may take a long time to bring about lasting change.

From a young age, girls from the Nat community are conditioned to enter sex work and generate income for their families. If they pursue education, they are less likely to enter sex work, which disrupts the family’s primary income source. The most success we have seen has been by engaging families to send their girls to school and college, emphasising that employment opportunities after graduation will enable them to provide income to their families.

Intervention at a crucial stage, when many girls are on the cusp of being forced into the profession, has been important. Since families either don’t have the means or the inclination to pay for education, we have directed efforts towards providing scholarships to girls as early as grade 6. To see intergenerational change at scale, these girls need to be supported continuously for at least nine years until they graduate, complete a skill-based course, or start earning. Continuous follow-ups help us support the girls’ education and hold families accountable, discouraging them from pulling their daughters out of school.

This approach, combined with village-level mobilisers closely monitoring each family’s situation, has proved to be the most effective way in slowly bringing about a mindset shift.

One of the most formidable obstacles we encounter is the influence of local leadership structures—such as the khap panchayat (a local-level caste council)—which often resist changes to traditional practices. For instance, Rajesh,* a khap panchayat member, initially spread negative perceptions about our project. However, when his daughters also received scholarships, he gradually began to cooperate and became an ally, even if discreetly. The khap panchayat’s endorsement remains crucial to any kind of social change, especially one that is rooted in caste. Without it, families often fear social ostracism and fines for defying community norms.

Yet, despite scholarship support, there are still girls who drop out of school or college due to family pressure and financial constraints, ultimately (re)turning to sex work. One team member shared, “When a minor girl is trafficked to Mumbai despite all our efforts, that’s when we feel most hopeless and demotivated.”

The team also faces community backlash when the police intervene in a case of a minor child being trafficked. In one extreme case, a family member attempted suicide to prevent the girl from leaving home to pursue education. Many cannot understand the benefits of formal education, as it is a slow change that takes generations to yield results. For instance, in the nine villages of Uniara block, there is only one girl in grade 9 who is studying further. None of the girls in these villages have passed grade 8 and many have been trafficked into sex work.

What is the way forward?

For nonprofits: Nonprofits must focus on creating sustainable interventions that impact entire communities and families, not just individuals. This approach allows them to break the cycle of exploitation. They must also strengthen community role models like Savita, so that there can be a generational shift that comes from within the community. Since we work on preventing minors from going into sex work, we have experienced a lack of a network of organisations with whom we can collaborate. Therefore, we believe that building networks of community-based organisations can facilitate collective problem-solving, reduce isolation, and enable long-term change.

For policymakers: Long-term policy reforms are essential to ensure intergenerational behaviour change. In the context of our work, this includes creating separate welfare categories for denotified and nomadic tribes (DNTs), removing bureaucratic barriers such as paternal documentation requirements, and establishing shelter homes for rescued children. Integrating trafficking prevention into health, education, and labour policies can create a protective safety net, enabling families to break free from exploitative systems.

Intergenerational change requires intergenerational funding

Many nonprofits work on issues that are either highly sensitive or yield results only visible in the long term, which often makes it challenging to get funding. As an organisation working to address commercial sex work among minors, we face significant challenges in securing donors. Many corporate social responsibility (CSR) agencies are hesitant to support this issue. Any mention of the words ‘sex work’ is enough to drift attention away from the cause.

Donors often prefer to fund nonprofits that can report measurable outcomes aligned with their targets. These agencies also expect immediate results, which is unrealistic when working towards behaviour change within communities that practise intergenerational sex work. Unfortunately, funders and stakeholders sometimes hold preconceived notions about certain marginalised communities, believing that even with years of effort and continuous funding, no meaningful change will occur. However, to challenge or break an intergenerational practice, intergenerational funding is required.

Conversely, some organisations recognise that behaviour change is a long-term process. With this understanding, they support nonprofits with a long-term vision, remain patient, and do not demand immediate results.

Addressing intergenerational change requires consistent engagement, patience, and a willingness to meet families where they are. In the Nat community, creating spaces for open conversations, offering alternative livelihoods, and supporting education provide young girls with the choice to break free from the constrictions of inherited socio-economic roles.

When we talk about long-term goals for the community, one of them is ensuring that no minor girl is forced into sex work and that children have their agency and the right to choose their own career path. We envision these villages having role models from the Nat community who will change the fate of the next generation through education and employment opportunities.

*Names changed to maintain confidentiality.

—