If one travels from Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh to Siliguri in West Bengal and then on into Assam, circumscribing the Brahmaputra and finally entering the Barak valley, one gets a panoramic sense of flood-prone India. This densely populated region—with a population density that exceeds 1,000 people per square kilometre—is prone to annual floods. Most of us hear about these floods only when they are very severe or catastrophic, as in the case of the barrage breach of the Kosi river in 2008. Otherwise they remain ignored and forgotten by the rest of the country. Poverty in the densely packed and perennially flood-prone plains in the Gangetic, Brahmaputra, and Barak basins is intense and has defied any solution till date.

Floods take many forms

There are several categories of flooding that often turn into disasters in this region. These include months of waterlogging due to drainage lines being blocked by river embankments, floods caused by water flows spilling over the river banks in rivers without embankments, severe floods caused by breaches in embankments, and flash floods caused by intense rains in the Himalayan hills, which often cause rivers to swell and change course. Riparian towns and cities such as Patna, Varanasi, and Guwahati are also flood-prone. The government and print and electronic media tend to take notice only when floods hit these cities. Occasionally, floods in rural areas of Bihar, West Bengal, or Assam are reported on as well.

Related article: Flood management—Looking beyond defence strategies

The most common occurrence across most flood categories is that water enters and fills up farmlands and habitations in villages. Flood waters rise high enough to drown the homes of people. Another occurrence—flash floods—are less common and the extent of loss to life and property usually depends upon the speed with which water enters and rises. There is very little scope to save much during a flash flood.

These periods of flooding also see a rise of health issues such as malaria, water-borne infections, and even snake bites.

In either case, people living in densely populated villages are forced to leave their homes and move to high points which remain above the waterline. These could be special structures (known as flood shelters) that are built by the government, highways, government schools, or even railway lines. Most of these shelters and refuges are very crowded, without sufficient access to safe drinking water or sanitation facilities. Women, people with disabilities, and the elderly suffer the most.

Known as sailab, floods that spread and inundate a region for long periods of time are also responsible for wiping out roads, which disrupts movement from one place to another. These periods of flooding also see a rise in health issues such as malaria, water-borne infections, and even snakebites. Unable to reach public health facilities, people adopt their own methods to live with these challenges. Often, they suffer in silence.

A good monsoon

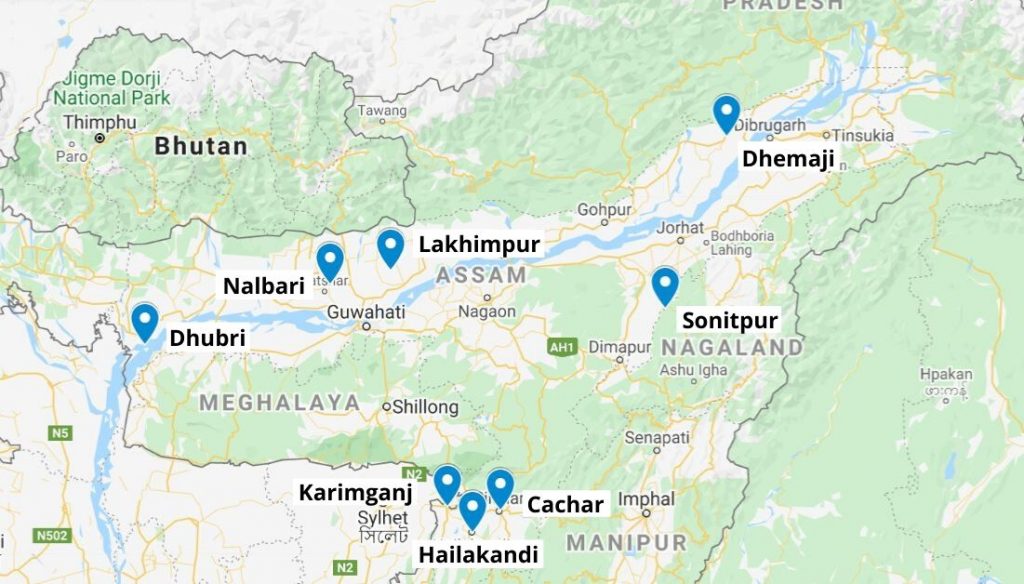

The weatherman predicts a good monsoon this year. Typically, this results in three or four cycles of floods in Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Sonitpur, Nalbari, and Dhubri districts in the Brahmaputra basin; Helakandi, Karimganj, and Cachar districts in the Barak basin and in districts such as Madhubani, Supol, Araria, and Khagaria in Bihar. In normal circumstances no pre-emptive plans to manage the likelihood of flooding in these regions would be made. We cannot allow that to happen this year as these regions will inevitably face the concurrent disasters of flooding, along with the spread of COVID-19.

Flood-prone districts of Assam. | Picture courtesy: Google Maps

Two groups of people are at particularly grave risk. The first is people who live adjacent to embankments that have weakened due to erosion or neglect. They are at risk of facing flash floods when these weakened embankments breach. They will need to run to save themselves and have little choice about where to seek refuge.

Flood shelters are typically overcrowded, with a few hundred people occupying a space with no access to safe drinking water or toilets.

The second is people who live between channels of braided rivers, as well as those who live on sandbars—strips of land that have created by sand deposits—that are known as diaras in Bihar and char or chapori in Assam. Due to continuous erosion caused by rivers, they are forced to put up with multiple displacements. Under normal circumstances, they are either accommodated in ‘new land’ that is created by the silt that is deposited by these very rivers, or are helped by local communities. With COVID-19 in the air, they would be unwelcome guests in nearby villages.

Flood shelters are typically overcrowded, with a few hundred people occupying a space with no access to safe drinking water or toilets and no way to reach health facilities, as roads are flooded or have been washed away. They could be stuck in these shelters for days, or even weeks. How would these people cope if COVID-19 were to spread at these shelters? How will they practice physical distancing? Where will they wash their hands other than in flood water contaminated with human waste? How can they prevent the disease from spreading and engulfing the entire habitation? How can quarantine or isolation facilities be created?

The most common occurrence across most flood categories is that water enters and fills up farmlands and habitations in villages. | Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Minimising the damage

It is entirely fortuitous that the state has a few months available to take advance measures to minimise the damage of the potential disaster. The Union Government has announced the PM Garib Kalyan Yojana and amplified support for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). These funds may be used to create raised platforms, that can be inhabited by families. Alternately, learning from the Sonwal and Mishing tribes of Assam, the government may help people create temporary houses on bamboo stilts. This can prevent crowding.

Related article: NREGA in the times of COVID-19

Land is intensely contested in these over-populated regions and Panchayati Raj Institutions and civil society could come together to educate people about the danger of the pandemic, and to persuade them to actively participate in these efforts by using their own patches of land for these raised platforms or stilted homes.

District Disaster Management Units must spring into action immediately. They need to urgently undertake decentralised planning to help communities cope with the simultaneous occurrence of a pandemic, along with the likelihood of flooding. The Assam State Disaster Management Authority has issued new guidelines for flood relief camps and a few districts have initiated advance planning to accommodate people during floods, with due consideration being given to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Local civil society organisations are also helping to create these plans. We hope that Bihar too will move in this direction.

This article is based on discussions during a webinar on Preparing to protect flood-affected people from COVID-19 by Transform Rural India Foundation and VillageSquare. The author acknowledges the contribution of Sarvashri Anil Sinha, Nirmalya Choudhury, Eklavya Prasad, and Prithibhusan Deka, who were panelists at the said webinar.

—

Know more

- Read about how communities in Bihar and Assam deal with annual floods.

- Read this article to learn about how the Kosi-Kamala floodplains demonstrate the importance of designing and managing infrastructure in a way that recognises floodplains as complex and intricate social-ecological systems.