In India, women continue to face discrimination as job seekers because of their gender. This discrimination is reinforced by the more than 150 laws that prohibit or limit women’s employment in certain industries—the generation of petroleum, the manufacturing of products such as oils and rechargeable batteries, and in establishments selling or serving liquor—especially during night-time. In 2022, Prosperiti analysed more than 200 regulations to understand which kinds of work women are excluded from. We also reviewed 26 judicial rulings to study how such discrimination is handled by courts of law.

In February 2024, we revisited the regulations identified in the 2022 report to see if the legal position regarding women’s work has changed in any way. We found that legal barriers largely continue to exist, with only a few states easing restrictions on women’s employment at night.

Listed below are our findings:

1. There are limitations on working at night in several states

There are 24 states with laws that limit women’s participation in various kinds of factory operations. Among these, there are 11 states that bar women’s employment at night. Two laws govern these strictures: the Factories Act, 1948, at the union level and the shops and commercial establishments laws at the state level. Governments have argued that these stipulations are necessary to prevent sexual violence and safeguard women from the physical dangers of longer working hours.

Even when women are allowed to work at night, the laws place several prohibitive conditions on their employment. For example, in most states employers must ensure that female workers make up a minimum proportion—either 10 or two-thirds—of the workers and the supervisory staff for the night shift. Such constraints make it difficult for employers to run night shifts with women workers, thereby reducing job opportunities for women. To illustrate: an employer would have to cancel a night shift if some women are on leave and there aren’t enough female workers to fulfil the two-thirds requirement.

Some states permit women to work at night in commercial establishments ranging from offices and theatres to warehouses and hospitals. States such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and Gujarat require inspectors to be “satisfied”, ensure that establishments provide “adequate protection of (women’s) dignity, honour and safety”, and mandate facilities such as shelters, restrooms, toilets, and night crèches.

Though Indian states have historically prohibited women from working at night, there have been gradual relaxations on this front. However, the pace of reform is slow. Since 2022, states such as Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have done away with laws that prevent women from working at night. Women in Andhra Pradesh are now allowed to pursue factory work at night, and those in Madhya Pradesh can engage in night-time work at commercial establishments. However, most other states, including Bihar and Rajasthan, continue to prohibit women from working at night in factories, while West Bengal continues to prohibit women from working at night in commercial establishments.

2. Women tend to be excluded from higher-paying jobs

Under the Factories Act and other labour laws, women are prohibited from working in various industrial processes even during the day. These laws are based on the assumption that some industrial processes may be too dangerous for women. The alleged heightened risk factor and increased susceptibility to accidents when women work with certain machinery led to bans on employing them in processes deemed dangerous or hazardous by state governments. Since 2022, no state has eased restrictions on women’s employment in ‘dangerous’ jobs. Women’s participation in new and growing industries and better-compensated work is also curtailed.

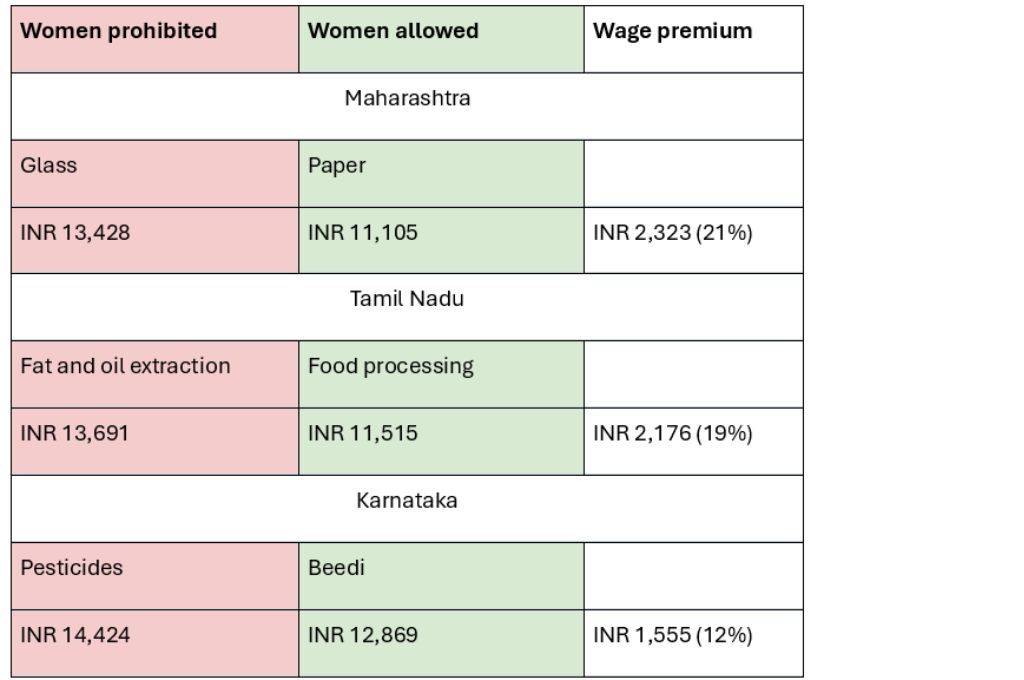

Even in traditional industries, the law may exclude women from jobs that pay more. Processes that women are prohibited from participating in—such as glass manufacturing and the processing of oils and fats—are generally better compensated.

The table below shows a comparison of minimum monthly wages in some industries from which women are prohibited and where women are allowed to work. The industries in which women are prohibited usually have higher minimum wages.

India’s 10 most populous states collectively impose 139 prohibitions on women from working in specific industrial processes ranging from electroplating and generation of petroleum to the manufacturing of products such as pesticides, rechargeable batteries, and so on. In many cases, there is no literature that identifies the special danger to the women, as opposed to the men, working in these jobs. Besides, these roles are open to women in some states and prohibited for those in others, which makes it evident that there is no scientific basis for exclusion. For example, women can be engaged in abrasive blasting (used for cleaning surfaces across industries) in Karnataka, but not in the neighbouring state of Maharashtra.

3. Moral policing furthers discrimination

Archaic laws continue to keep women out of various types of jobs that are considered incompatible with the gendered expectations that society has of them, such as working in liquor establishments. The prohibitions are based on the belief that it is morally inappropriate for women to serve liquor in public. For example, according to the Punjab Excise Act, 1914, this restriction is necessary as it prevents “the woman folk from becoming addicted to the intoxicants and avert and avoid any conflict between sexes and chances of foreseen sexual offences”.

Among India’s 10 most populous states, West Bengal does not allow women to participate in the alcohol serving/selling industry at all. Even in the states where women are allowed to participate in the alcohol service industry, their involvement depends on the type of alcohol being served, a rather arbitrary criterion. India divides the alcohol industry into two classes—country and foreign liquor. Some states allow women to participate in one while barring them from the other. Women in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra can serve/sell foreign liquor, but not country liquor; on the other hand, women in Andhra Pradesh can serve/sell country liquor, but not foreign liquor. In other states such as Telangana, women can secure a licence to sell foreign liquor, but cannot work in establishments serving foreign liquor.

There have been a number of court judgements that have upheld women’s right to work at liquor shops. However, these interventions haven’t led to a change in state laws and women’s employment in such establishments continues to be penalised.

How can women’s workforce participation be improved?

The situation on the ground won’t become better without a change in the perceptions and laws preventing women’s employment. The government and policymakers can enable this by:

1. Addressing gender stereotypes in legislation

Gender differences should not be used as a basis for greater disparity through legislation. Many Indian laws continue to be influenced by stereotypes and promote discrimination rather than eliminating it. It is high time that such antiquated laws are amended to align with international frameworks put forth by Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Several states and courts are beginning to question and overturn discriminatory laws based on outdated stereotypes and their harmful impact on women’s economic roles. Regions such as Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, and Punjab are issuing exemptions to factories through government orders informed by landmark decisions, such as Vasantha R vs Union of India. In the Vasantha R decision, Madras High Court struck down the law forbidding women’s employment at night as unconstitutional and laid down model conditions subject to which they could be engaged in night-time work. State governments have used these models as templates to set conditions within their respective jurisdictions.

2. Providing clarity on the implementation of laws

Currently, laws can be changed by the state government through three different legal instruments: amendments in acts, amendments in rules, and by issuing government orders. Additionally, laws can be pronounced—wholly or partly—unenforceable by court judgments.

When acts are amended but rules are not revised in keeping with the law, it can create confusion. Take, for instance, the Uttar Pradesh Factories Act and Rules, 1950. While a 2017 amendment in the act removed the restrictions on the employment of women in night shifts, the Uttar Pradesh Factories Rules, 1950, which continues to be valid, states, “No woman shall in any circumstances be employed in any factory more than 9 hours in any day or between the hours of 7 pm and 6 am.”

A more streamlined approach to the implementation of laws and amendments would ensure that the progressive measures taken by states actually benefit the working women.

3. Ensuring safety at the workplace

Prohibitions on women’s work were first adopted based on a paternalistic approach toward women’s safety. However, these laws continue to exist in our statute books because government functionaries are risk-averse. They worry about opening up industries to women because they may be blamed for mishaps that some women may experience. The solution to the problem may involve greater public awareness and acceptance of risks and planning for their mitigation. Instead of making it overly expensive or operationally difficult to employ women, state governments can make sure that companies deploy safety measures such as CCTV and GPS-enabled transportation to ensure women’s safety.

It is important to consider that restricting women’s work creates greater poverty for women, which has its own health and safety implications.

Suyog Dandekar and Eknoor Kaur contributed to this article.

—

Know more

- Listen to this podcast to understand how gender norms shape women’s access to the workforce.

- Read this article to learn more about women’s employment in India’s factories.