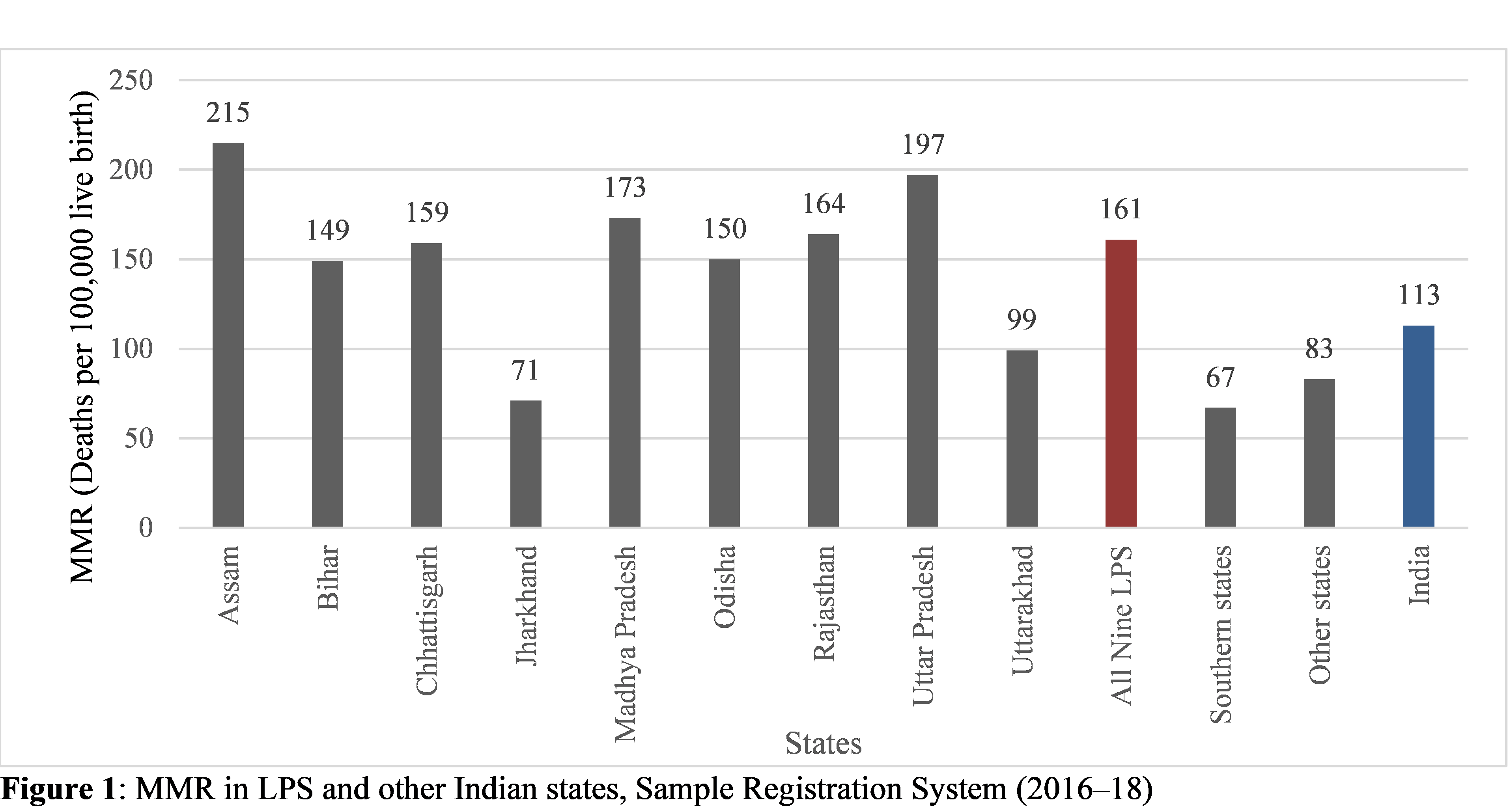

Between 1990 and 2018, India has made notable progress in reducing its maternal mortality rate (MMR). However, this progress has not been uniform throughout the country. Low-performing states (LPS) such as Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand still have a relatively higher MMR as compared to the national average (Figure 1).

A key component of maternal healthcare is institutional delivery, which reduces the risk of preventable maternal and neonatal mortality arising due to delivery-related complications. To promote and improve the uptake of institutional deliveries in India, the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) was implemented as India’s flagship scheme under the National Rural Health Mission in 2015. It has been designed to reduce high out-of-pocket payments and associated catastrophic health expenditure incurred at the point of care. JSY offers centrally sponsored conditional cash transfer incentives—upon delivery and throughout postnatal care—to beneficiaries delivering at public health facilities and authorised private hospitals registered under the scheme. The amount of financial disbursement differs across states, with LPS receiving nearly double the amount (USD 13.6–19) compared to the high-performing states. JSY also provides beneficiaries with free transportation services to healthcare facilities and accredited social health activist or ASHA-led prenatal and postnatal care. Despite these incentives, the coverage of institutional delivery remains extremely low in specific subnational regions and among socio-economically disadvantaged groups. It is especially stark in India’s nine LPS, which contribute to 12 percent and 62 percent of all global and national preventable maternal deaths respectively.

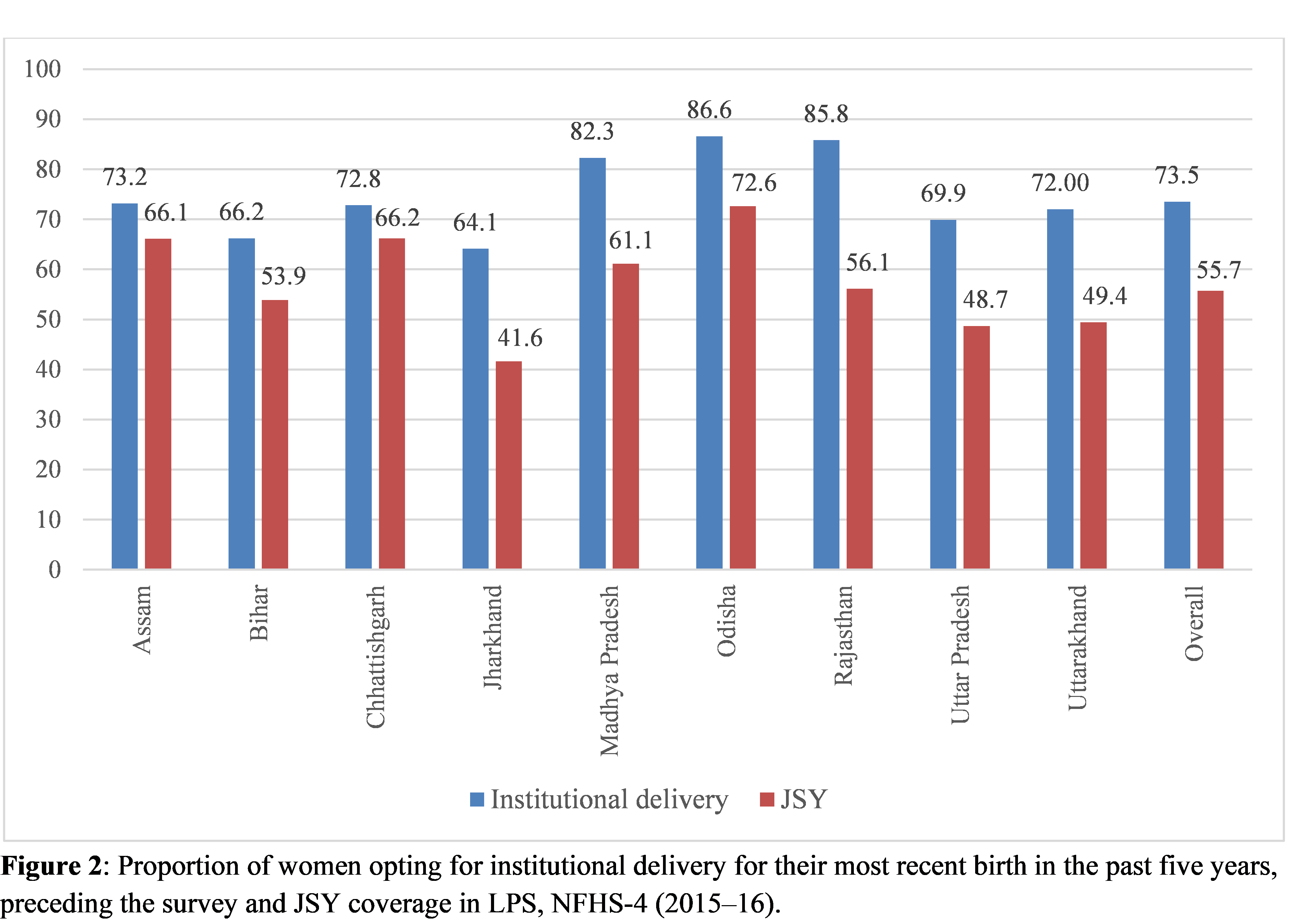

To further understand the relationship between institutional delivery utilisation and JSY scheme coverage across these nine LPS, we analysed data from the National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4), 2015–16. Our findings indicate that states with the highest institutional delivery coverage had a high JSY scheme coverage and vice versa. In Odisha, for example, both institutional delivery (87 percent) and JSY coverage (73 percent) were found to be high. In contrast, in states such as Bihar where uptake of institutional delivery was lower (66 percent), JSY coverage also remained low at 54 percent (Figure 2).

These findings raise a few other important questions: First, despite comparatively high institutional delivery coverage, why does MMR remain high in states such as Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan? And, second, why does the uptake of institutional delivery as well as JSY utilisation remain low in states such as Bihar and Jharkhand in spite of monetary incentives? On probing these questions further, we found that a range of socio-demographic factors (beyond financial incentives) determine whether or not a woman will opt for institutional delivery.

Accessibility to health facilities

Even though there has been a committed emergency transport support system under JSY, beneficiaries still face difficulty in accessing them, sometimes due to unavailability or severe delays. We found this to be the case, especially for women residing in the rural areas of Assam, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. Our findings indicate that transport-related challenges, coupled with the overall lack of health facilities, resulted in more women in rural areas opting for unsafe home deliveries as compared to their urban counterparts.

1. Household poverty

The second important factor that determined the uptake of institutional deliveries was household wealth. In Assam, women from the richest households were 14 times more likely to deliver in a health facility compared to the poorest households. We found a similar pattern in other states such as Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. Evidence suggests that even though JSY offers cash incentives, beneficiaries face several obstacles in obtaining them, with untimely cash disbursement being a major issue. Women from poorer households are unable to account for and make some of the necessary payments in advance. For example, in rural districts of Madhya Pradesh, women reported that they did not receive the entire cash reward upon institutional delivery. This is because they had to make forced side payments to the hospital staff, ASHAs, and incur other transport and medicine expenses—all of which were deducted from the cash reward. In addition to this, beneficiaries also face problems while opening local or regional bank accounts and are unsure of when and exactly where their cash rewards will be deposited.

2. Child marriage

Across the nine LPS, we found that child marriage also deterred institutional deliveries. This may be attributed to the lack of autonomy and restrictions imposed by family members on child brides. Overall, women who married before the age of 18 were 22 percent less likely to opt for institutional delivery than women who married at 18 years or later.

3. Education

In our study, education emerged as an important determinant across all the states. Women who had higher educational attainments were almost four times more likely to utilise in-facility birth compared to those who were less educated. The importance of education was majorly observed in the states of Assam and Chhattisgarh where it appeared as the second most important predictor of institutional delivery. Drawing from our research, we can infer that access to education over time could equip women to be more aware of the clinical health benefits of delivering at a health institution.

How can we improve institutional delivery coverage?

Conditional cash transfer incentives under JSY have not proven to be sufficient and satisfactory in escalating the demand for and utilisation of institutional delivery services. However, state-specific solutions can help improve the uptake of safe in-facility deliveries among beneficiaries; this is integral to their sexual and reproductive health rights. Here are a few suggestions:

1. Awareness campaigns

Awareness programmes centred around the benefits of JSY along with promoting state-specific schemes, such as MAMATA in Odisha and Mukhya Mantri Shramik Seva Prasuti Sahayatra Yojona in Madhya Pradesh, can help communities make a better-informed decision when opting for institutional delivery.

Interaction with community health workers such as ASHAs emerged as a strong facilitator of institutional delivery across all states. Therefore, regular and uninterrupted high-quality antenatal counselling sessions could adequately equip beneficiaries with knowledge of clinical health benefits of in-facility delivery, thereby improving health-seeking behaviours (escalating demand for institutional deliveries).

Increased and sustainable investments in training, recognition, and retention of skilled health personnel at all tiers could ensure optimal care for both mothers and newborns.

As indicated by findings in our study, the utilisation of institutional delivery is also influenced by conservative sociocultural norms. Hence, context-specific socio-behavioural change awareness programmes and interventions that focus on preventing child marriage practices and early pregnancies are crucial for improving institutional births and overall maternal health.

2. Improving quality of care

A recent study highlighted the acute lack of a skilled healthcare workforce in India, with numbers barely meeting the WHO-recommended threshold of 44.5 skilled health workers per 10,000 persons. This deficit of skilled healthcare professionals directly impacts the quality of available essential maternal care, potentially resulting in low institutional births. Exposure to poor-quality maternity care (tragic or negative birth experience) can also instigate a fear of childbirth and pregnancy-related anxiety, which may dissuade women from opting for further institutional deliveries or returning for necessary postpartum check-ups. Although India has recently integrated midwifery care into its health system to bolster the quality of maternal and newborn services, an acute shortage of skilled healthcare providers over time has resulted in a highly inadequate skill mix of doctors and nurses/midwives.

Interaction with primary healthcare workers and strong referral networks across various levels of the healthcare system can lead to timely and improved quality of care for women.

Since high institutional delivery coverage has been unsatisfactory in reducing maternal deaths (observed particularly in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Rajasthan), specific subnational policies should not only focus on increasing the number of public health facilities but also on improving the quality of maternity to be more person-centred. Increased and sustainable investments in training, recognition, and retention of skilled health personnel at all tiers, especially in primary health centres, are critical to effectively improve safe delivery care and ensure optimal care for both mothers and newborns.

3. Investment in reducing system-level barriers

Interaction with primary healthcare workers and strong referral networks across various levels of the healthcare system can lead to timely and improved quality of care for women. In addition to this, establishing more transparent and accessible systems under JSY to improve transport facilities and reimbursement mechanisms can encourage women to opt for institutional births.

—