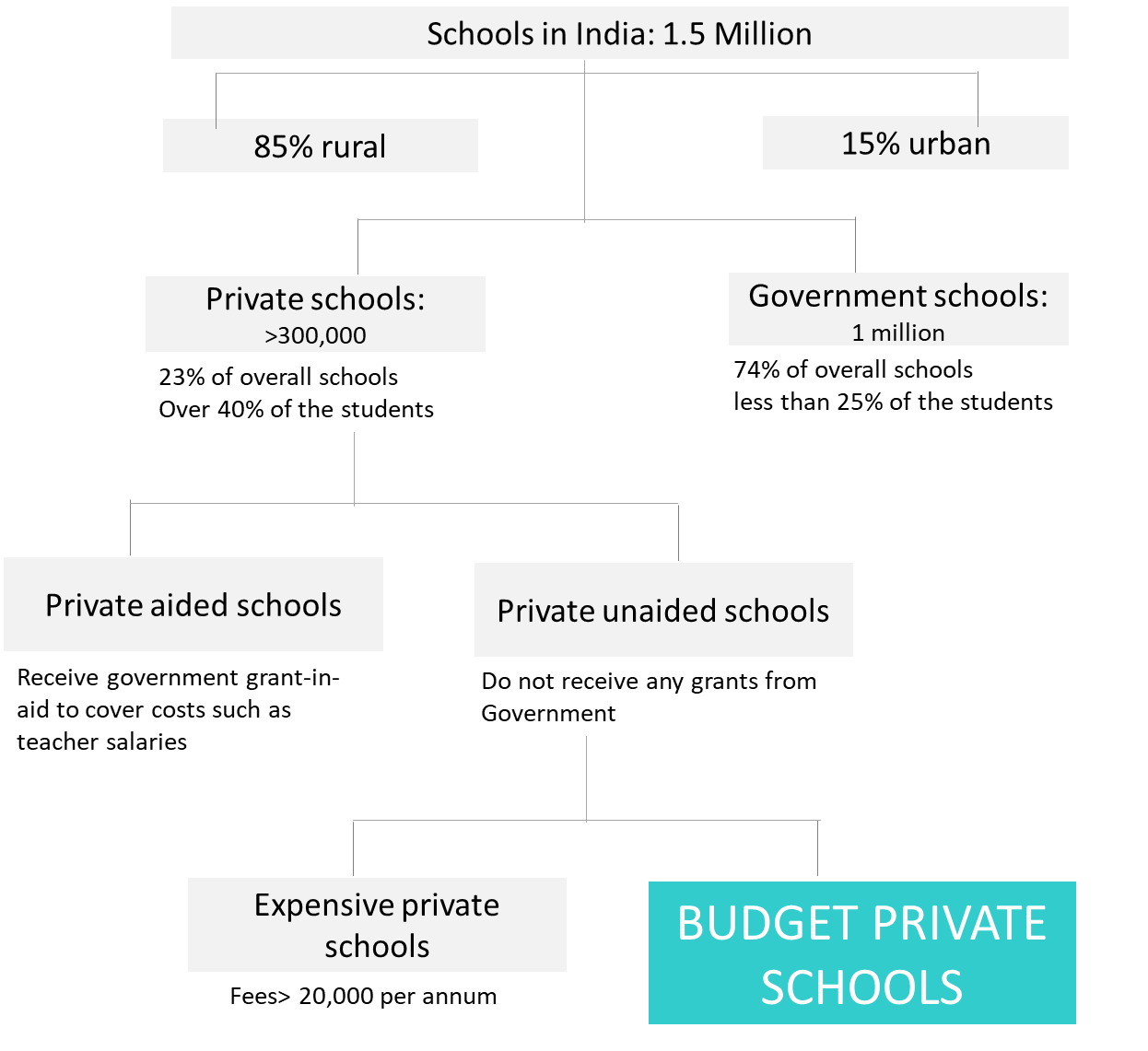

With a nation of 260 million children attending over 1.5 million schools, education is at once deeply personal and intensely political for Indians. Over the last decade, we have seen a drastic change in the ownership of schools, with private schools, though fewer in number, multiplying rapidly.

As of 2011, there were 170 million children enrolled across government and private schools. From 2011 to 2015, based on reported data from Unified District Information System for Education (U-DISE), the total enrolment in government schools fell by 9 percent, or 11.1 million students.

However, overall student enrolment in schools did not fall during this period. The drop in government school enrolment was accompanied by a 36 percent increase (around 16 million students) in private school enrolment. While there are different government categories of private schools, one category has been growing rapidly across rural and urban India: budget private schools (BPS).

Charting the rise of private schools in India

As independent profit-making entities that provide education, budget private schools face ire and support in equal measure. Ire from those who believe education and profit are not natural allies. And support from parents who believe these schools offer them an affordable education (less than INR 15,000 in annual fees) for their children.

‘The Preschool Promise’, a study by FSG, looked at preferences of 4,407 parents from low-income households across eight cities—Delhi, Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Kolkata, Nagpur, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Coimbatore—and found that over 86 percent of the children from these households were already enrolled in BPS or would transition to them in the Grade 1. Clearly, there is preference among parents for such schools.

While the reasons for this vary widely—and we are yet to gain a deeper understanding of this shift—anecdotal evidence tells us that it is a trend worth paying attention to. Primary discussions with more than 20 school leaders, teachers and parents across Assam, Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Nagaland, Punjab and Telengana, as well as cities such as Ambala, Bangalore, Chennai and Coimbatore, for a 2018 BPS report by Centre for Civil Society revealed the main reasons why parents are choosing BPS.

First, these schools tend to be situated right in the community, making it easier for children, especially girls, to attend. Second, learning English, which is integrated as a subject in the BPS curriculum, is an aspiration many parents have for their children. Third, parents find lower teacher absenteeism and greater accountability for learning outcomes at BPS. Simply put, parents believe their children will learn better in these schools and are therefore opting to pay for the education.

The break-up of schools by categories (2016)

Despite the rise in BPS, there is very little public information about the schools. U-DISE data clubs both private aided and private unaided schools as a single category, making it very difficult to estimate the actual number of BPS. Moreover, some of the unrecognised schools remain excluded from the overall count, causing under-reporting to an unknown extent.

As private entities, BPS are part of a highly fragmented landscape. In the absence of official data, multiple estimates from Dr Geeta Gandhi Kingdon, Prof James Tooley and FSG suggest that approximately 200,000-400,000 budget private schools with about 60-90 million children are expected to go through BPS schooling over the next few years. That’s about 30 percent of all our students.

A recent FSG report on the BPS market in India describes a typical school owner as an individual or a family that may not have a prior background in education. Most of these schools are small—about 400 students—and operate until Grade 8. Few exceed 1,000 students. While basic facilities are in place, many schools lack playgrounds, libraries, science and computer labs. BPS leaders struggle with parent engagement, fee collection, space, and teacher recruitment and retention.

Some look upon themselves as social entrepreneurs, bringing education to children within their community while trying to simultaneously build a business. Like any entrepreneur, they offer services, incur costs and make profits. And some, in their own way, try to innovate within their schools, defining their own versions of what a quality education entails. In addition to teaching government curriculum, different budget private schools adopt different approaches and focus areas, often based on the entrepreneur’s vision and/or the local community’s needs.

The opportunities and challenges of BPS

With 260 million school-going children in our country, government schools alone will not suffice to meet the demand for education. We also know that independently-run budget private schools, though a fraction of the overall schools in the country, are growing in demand and number.

As a nation, we have focused and, to some extent, solved the problem of enrolling our children into primary schools. Yet, we have barely scratched the surface on the question of quality of education, with learning outcomes having pretty much stagnated over the past several years.

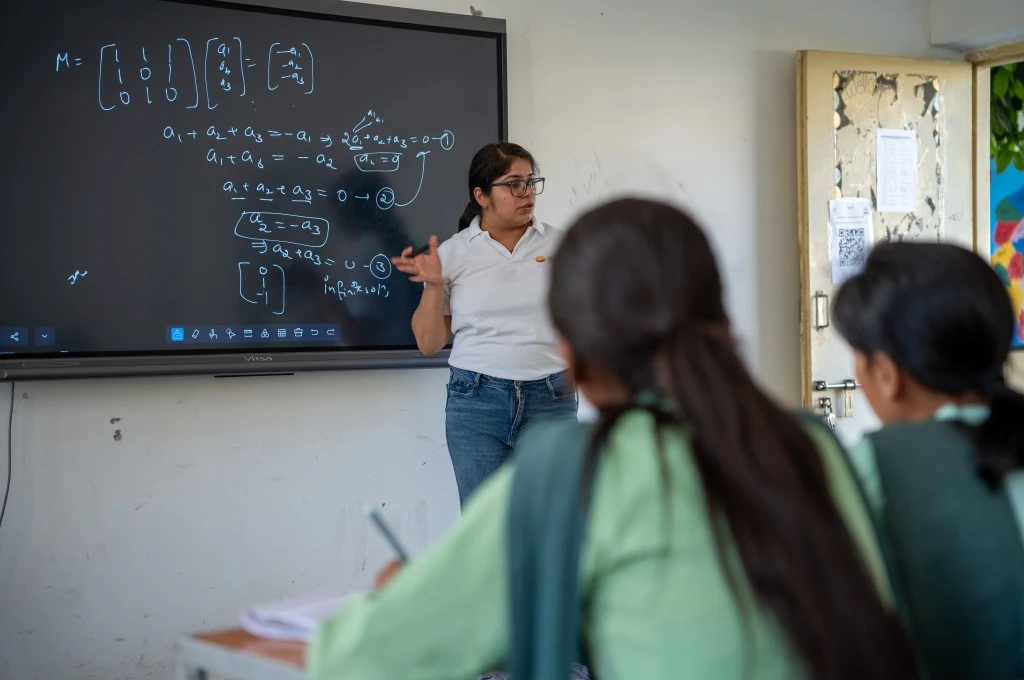

Picture courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

While the ‘evidence’ on BPS is weak and the picture we have is still very fragmented, by virtue of these schools being unbeholden to others in ways that government schools tend to be, there is greater potential to innovate. Their local, community-based experiments could offer practical solutions for bridging the gap that we see in learning outcomes today.

Cost effectiveness is another factor in favour of BPS. FSG’s studies and primary insights from BPS leaders show that successful schools can achieve profit margins of more than 20 percent, and sometimes as high as 50-70 percent. This means that successful BPS can pump money back into improving their institutions and the quality of their education.

Dr Geeta Gandhi Kingdon’s calculations supplement those of FSG; she says that it is about 40 times more cost-effective to produce one unit of achievement in private schools compared to government schools. In her research, she has compared the per pupil expenditure of government and private schools with reported achievements in reading and numeracy to find an efficiency comparison.

BPS owners are consummate at understanding the aspirations of parents and providing towards them.

As entrepreneurs, the BPS leaders are more inclined to pay attention to customer satisfaction. As Maya Chandrasekharan at Menterra Venture Advisors, an impact investing fund supporting education start-ups, says, “If run efficiently and in an area with strong demand, BPS can become cost-effective and even steadily profitable. Like all successful entrepreneurs of a consumer product, the BPS owners are consummate at understanding the aspirations of parents and providing towards them.”

However, the these schools are not without challenges. They need to have a strong vision, good teachers and continuous teacher training to provide quality education. Because they target low-income populations, their fees are not always paid on time, impacting their working capital. As startups, they struggle with complying with a host of blanket regulations that do not differentiate fee-based schools from a government/free education.

State-level regulations impact BPS as well. Vikas Jhunjhunwala, a school leader at Sunshine Schools in Delhi and UP, points out: “Land laws and nonprofit structures in education create entry barriers in the low-fee school segment. States such as UP, which have softer land requirements, see much higher supply of such schools and higher cost-efficiency.” Also, the lack of research and evidence, including on BPS curriculum, learning outcomes, classroom interactions and processes, and the quality of teacher-learning processes make it very hard to assess these schools collectively.

Will private unregulated educational institutions create more gaps in data, and what does this mean for policy?

The bigger questions to ask are, if budget private schools—all of which operate as independent entities in a highly fragmented market—continue to grow at this rate, what are the implications for education outcomes in India? Will private unregulated educational institutions create more gaps in data, and what does this mean for policy?

Given the growing demand among parents for BPS, do we invest in developing this market, or do we focus on improving the quality of education in our government schools? I don’t have a definitive answer, but I would follow demand and put my money on budget private schools.