Edited transcript of the episode:

01.50

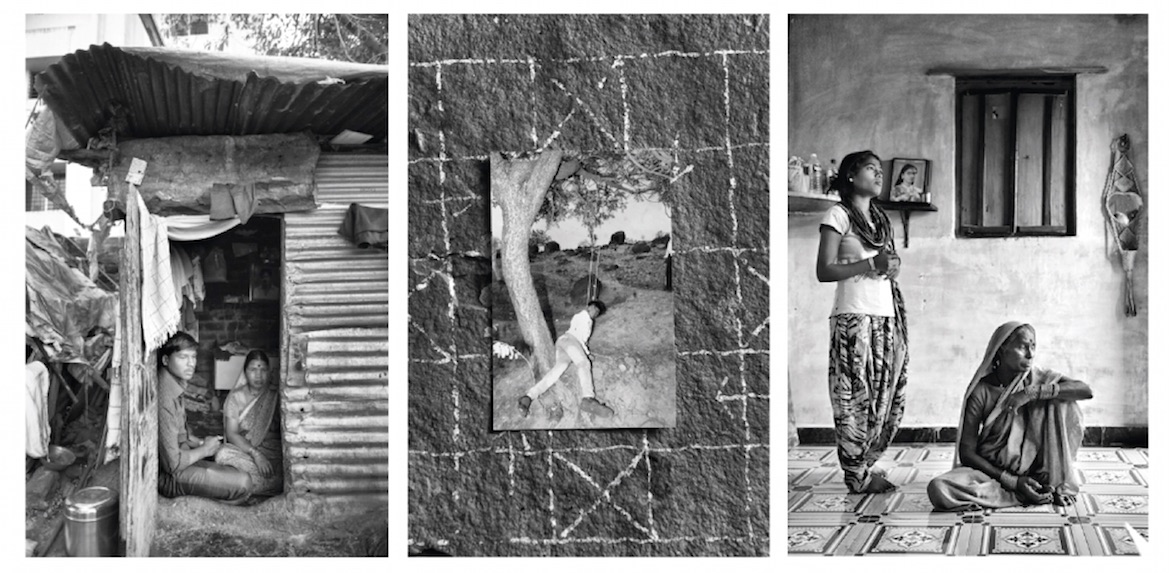

Smarinita: If one were to search online for the caste system in India today, what would get thrown up most prominently would be reports of caste-based violence and discrimination. This is despite the fact that we have numerous laws that prohibit oppressive caste-based practices. But the law is one thing, and reality is something else altogether.

Newsrooms, boardrooms, classrooms, and several other formal institutions are still occupied by those belonging to the dominant castes.

In a report published in 2019 by The Media Rumble (Newslaundry) and Oxfam India, it was found that out of 121 leadership positions surveyed in newsrooms, none were held by those belonging to scheduled castes or scheduled tribes, which is why we are probably seeing social media increasingly beginning to function as a platform for anti-caste voices and conversations, primarily because it doesn’t have too many gatekeepers. But there is still an urgent need to break into more mainstream forums, convenings, and organisations.

Savarnas, or those who occupy ‘the higher rungs of the caste hierarchy’, often talk about being anti-caste allies or about ‘passing the mic’. But what they often fail to acknowledge is that the mic was never theirs to pass.

What then must change in the system for caste-marginalised people to take centre stage? How can anti-caste allyship move beyond lip service and cede power?

Our two guests today—Christina Dhanaraj and Dhanya Rajendran—will discuss what it really means to be an anti-caste ally, and the role institutions and individuals must play in the movement.

Christina Dhanaraj is a writer, with more than a decade of work experience in India, Singapore, China, the United States, and the Netherlands. She is a consultant for women and minority-led initiatives focused on social justice, self-determination, and collaborative models of scholarship. She is currently an adviser for Smashboard, Dalit Women Fight, and The Blue Club’s Media Fellowship for Dalit women. She was also the co-founder of the Dalit History Month project.

My second guest—Dhanya Rajendran—is the editor-in-chief of The News Minute, which has established itself as one of the most credible sources of news from the five southern states. Dhanya is also the chairperson of DigiPub, India’s biggest association of digital media publishers. Previously, she worked as the South India head for the English news channel Times Now.

04.11

Smarinita: My first question is for you, Dhanya. We know that institutions play a critical role in shaping and reinforcing narratives. Given that almost all of them—whether it’s the media, judiciary, or universities—are dominated by the upper castes, who are unlikely to give up power, what do you think can be done to change some of this?

Dhanya: So I think that affirmative action is very important, and institutions have to be careful and thoughtful when it comes to affirmative action. It has to be followed in all organisations, whether it’s government, private, etc. In fact, I was looking at statistics which the Union Government gave recently in front of the Supreme Court. They had looked at, I think, around 19 government departments and found that the OBC representation was quite okay, but the SC/ST representation was problematic in the sense that most of the people who got jobs were in class II and class III. There were very few people in class I. So, even when we look at affirmative action in government jobs itself, after so many years, why is it that people are limited to jobs in class II or class III in the government? And these are statistics given by the government itself. In fact, I could have been wrong. I think they said that when it comes to OBC reservation or affirmative action also, the number is not quite good enough.

After so many years of affirmative action, why have we not been able to ensure that it’s percolated into every segment?

But these are questions before us, right? As a country, as institutions, as governments, how have we failed? After so many years of affirmative action, why have we not been able to ensure that it’s percolated into every segment? For example, I remember a debate in which someone randomly said, “Oh, there are a lot of people from these communities who do get government jobs.” I remember someone else interjecting and saying, “It’s not just about them getting jobs, it’s also about whether they rise in the hierarchy.” And I think that applies not to just government institutions, but even to the media or any other institution. Yes, we talk about more representation and about bringing more people in, but do they still remain at the lowest of the hierarchy and not move up in their jobs? We do not have chief secretaries and joint secretaries in the bureaucracy; we do not have editors-in-chief in the media. How does it matter, if all of them are still class III employees of the government or if in the media they are merely reporters who do not take any calls in the organisation?

So I think these have to be addressed more actively. From the industry that I represent, I do know that it is largely a Savarna media. Most editors are either Savarna men or women, and that has not changed over the years. In fact, things have not changed to such an extent that I think a lot of people are dejected, and I see this parallel movement of websites that are run by people from Dalit communities and others because they believe that they are not represented in other media houses. There are more proactive things that organisations need to do, right from the time of hiring to promotions, and to ensure that there are more people who rise up in the hierarchy.

I think it’s just not enough that we take people in; we have to ensure that they become decision makers. I’m not sure whether this is going to change for the next few years—at least the next 20–30 years—considering that people are not moving up the hierarchy. And there is so much negativity, there is so much of a dialogue against affirmative action. Therefore, we need to change the dialogue itself. We need to tell people, “Look, [despite] this many years of affirmative action, we have only made this many steps forward.” There’s so much more to gain. I think nobody should be under this misconception that a lot of gains have been made because of affirmative action or reservation for so many years.

07.59

Smarinita: Thanks, Dhanya. You spoke about how the civil service posts or government jobs in India have been classified as class I, class II, or class III, with class I being the managerial or highest class of employees, followed by class II, and so on. So while people from caste-marginalised backgrounds have access to these jobs, like you mentioned, this may only be happening in class II and class III positions, and not so much in class I. So there is clearly a need to create an environment that enables them to also take on decision-making roles and higher ranking positions. But if there’s resistance, especially in terms of mindsets, how then does one counter that? Because people in power tend not to yield their power. So, how does one change some of that? Christina, could you weigh in?

Christina: I do believe affirmative action is absolutely important. Representation is absolutely important. These are some of the basics that I think we should all already be on the same page about. And by ‘we’, I don’t just mean the three of us in the room today, but also the country at large—the state, organisations, institutions, and companies. All kinds of entities should already be believing in something as basic as this. But thanks to the context that we are all operating in, my fear is that affirmative action or the case for affirmative action and the case for ‘reservation’ is going to get more and more challenging. The more we are going to have conversations about how people from SC/ST are already in these positions, the stronger the counter against practices of affirmative action will get. So, given that context, I think it’s probably time for us, like Dhanya just mentioned, to change the dialogue around it and also perhaps the strategies around it.

Given that we are going to fight for affirmative action in such a challenging context, how do we ensure that more people are going to come in from caste-marginalised backgrounds, without having to do it only through formal methods or formal channels?

To give you an example, within the corporate space, which I have been part of for the last 12 and a half years or so, I can assuredly say that if we were to take the formal route of having more people from caste-affected communities, we are not going to get anywhere because it’s going to be a fight that’s going to go on forever. Even if we’re not talking about it, even conversations as rudimentary as “we need to have caste-based diversity and inclusion” being part of the larger D&I conversation is instigating people into talking about reservation, and they go on to this massive sort of ‘fight mode’. And if we are going to take that route, it’s never going to come through. We’re going to be waiting for another decade, or maybe even 20–30 years before we have a significant percentage of people from cast-affected communities within the corporate space, let alone them rising in the hierarchy. Even having people in analyst positions—regular, not-so-middle management positions—is difficult at the moment. And to even envision that they would be CEOs and be part of the C-suite is just completely unimaginable right now.

So, I think it’s time for us to think about what are some of the informal ways of getting people in? What are some of the ways in which we don’t have to necessarily ask people to be out with their caste identity? We don’t necessarily have to shake people by saying, “Are you really from the Dalit community or not? Only then we will take you in.” I think those kinds of formal routes also give way to tokenism, as people bring them in because you have to satisfy a certain standard, parameter, or metric. And then you don’t have the atmosphere that’s conducive enough for them to grow in that system.

It’s not just about getting people in, but also about creating a culture and an environment where they are made to feel full and complete, and we are able to thrive.

And at the end of the day, they just leave the organisation. I’ve had to leave the corporate space, because the entire time that I spent there, I was invisibilised. I was made to feel worthless, despite showing up over and over and over again. So, I feel…couple of things—one, formal routes are absolutely important, we need to have those and not erase them completely. But, at the same time, we should also give space to start thinking about some of the informal ways in which we need to bring people in, whether it is job advertisements, whether it’s word of mouth, whether it’s very proactively looking for people from caste-marginalised backgrounds to bring into organisations. And, thirdly, it’s not just about getting people in, but also about creating a culture and an environment where they are made to feel full and complete, and we are able to thrive, right? That’s definitely something that I’m in agreement with. But I’m also aware that I’m speaking with a corporate space in mind, so I’m sure all of this will have to change and kind of evolve and shape up depending upon the context you’re working with.

Maybe in a university space, it would look very different. Maybe in a public sector space, it would be very different because in public sectors, you tend to have some of these very formalised [practices], and yet people don’t necessarily feel that they could still rise in the hierarchy because there is a system in place. So, these are also some things that we need to keep in mind when we are envisioning what representation across the levels looks like.

13.46

Smarinita: You both have spoken about how we should be thinking of getting caste-marginalised people in—how we all can create the environment and look beyond just formal strategies. Because when we talk about institutions, at the end of the day, they are really made of people. And you need individuals as allies to push the movement and the agenda forward. While caste-marginalised people need to fight the fight, we also need dominant castes at the other end to stand up there, cede space, and create a conducive environment. So, as individuals sitting within the spectrum of institutions that you spoke about, what is the role that they must play?

Christina, you have spoken before about how when Savarnas are working as allies, they occupy most of the speaking space—the space where conversations happen. What do you think Savarna allies should do more of, or less of?

Christina: Sure, I’m going to try and answer this question not just within the contours of an organisation, but also outside of it. Perhaps there are some lessons that we can take and kind of envision how to implement some of these basic principles. I think over a period of time, and thanks to the last few years of us thinking about what allyship looks like, particularly within the context of caste, and because some of these conversations are either driven by or sustained by caste-oppressive communities, I feel that, in the last few years, the way anti-caste discourse has kind of shaped up has somehow made us realise that this is all about making better allies out of caste-powered people. That very thought needs to go through an overhaul. We need to completely change that and flip that around. For me, as a Dalit woman, I feel Dalit communities must be at the centre of these anti-caste discourses. They must be at the centre of anti-caste progress. So if I were to place caste-marginalised/caste-affected communities at the centre, and if their progress, their livelihoods, their success, happiness, and thriving is what matters so much, then what does allyship look like? What would the allies have to do? Not so much as to become better people and better allies, but what should they be doing in order to get the people who are sitting in the centre to become much more than what they’ve been led to become?

The best way to start that very long, arduous, and complex process of ridding ourselves of caste and casteist mindsets is to have caste-marginalised people at the centre of this change.

Because we’ve had thousands and thousands of years of an oppressive state in place, of an oppressive system in place, and we’ve barely understood how caste has expressed itself within these spaces. We don’t even fully understand how caste translates itself within interpersonal relationships. And so the amount of change—the level of overhaul that we require out of people and out of systems—is really, really huge. And I think the best way to start that very long, arduous, and complex process of ridding ourselves of caste and casteist mindsets is to have caste-marginalised people at the centre of this change and not to think that Savarnas, as people who are holding the stage, should pass the mic, open up spaces, or include people. Because all of these sorts of discourses are assuming that it’s Savarnas who will continue to hold power, who will continue to be at the centre of it, and who are just including people from the outside. I say, “Stop that,” and get to a place where you’re having caste-marginalised people at the centre. And then you can think about what it is that I have to be doing in order to get them to hold power, hold the conversation, set up the stage, and create discourses that are applicable for them.

If we were to take an example, say if you were to think about writing, we tend to think that as a writing community, the people who hold publishing companies will have to give opportunities to Dalit authors. But most often even that is not happening. But if we were to flip that whole thing and think about what would a publishing company with Dalit people on the editorial board, as chief editors or as commissioning editors, look like? What kind of books would they be commissioning? What kind of stories would they be telling? What kind of people would they be inviting for anthologies? So I think it’s important for us to flip that imagination and think of it as caste-oppressed and caste-marginalised people being at the centre, holding power, and being the ones originating these very discourses, rather than still having caste-powered people at the centre and thinking of how they can be better allies and bringing more people in.

19.00

Smarinita: Dhanya, I’m going to come to you because you’re the editor-in-chief at The News Minute—is there a role that media plays in all of this and how narratives get shaped?

Dhanya: Yeah, so I will speak on that, but I just want to address something that Christina said on allyship. So I completely agree with her, as being a Savarna woman myself and a Savarna editor, what I’ve learned over the years is that, like Christina said, these movements have to be led by people from caste-marginalised communities and we have to learn to listen to pass the mic, surely.

But I also think that one trend I have noticed amongst the atoning Savarnas, as I call them, is that they simply want to listen sometimes and keep passing the mic. And they don’t think that they have anything to do other than pass the mic, which I think is problematic too in the sense that they don’t want to get involved at all as they think someone else will do the job. So, I think most difficult conversations have to occur amongst Savarnas themselves. Like, for example, I specifically remember, in my friend group, people would say, “But we never spoke about caste in school,” or “But we were never casteist in school.” Once I had to actually point out to my whole bunch of school friends that we are the greatest example of a gang where everybody is a Savarna. So, I told them that look, we may not have been casteist, but the point is that from the time we are born, there are ways in which we come together, right? It’s sort of inbuilt in us because our parents have told us in various different ways. And, okay, maybe I was not [explicitly] casteist, but I was [implicitly] casteist in many ways, because I do know that this is the way—this is the gang I should make, these are the friends I should have, or these are the people I should hang out with. These are very intrinsic in us, and I think we have to have those conversations amongst ourselves. And when someone criticises us or calls us out, I think to immediately feel victimised [and think], “Ninety-nine percent of the time, I have been an ally; the one time I did something wrong, why am I being called out?” is also something that I’ve been noticing lately. So, to me, I tell myself that I’m not being punished for the sins of my ancestors. But I have to be educated, I have to be aware of what happened. Therefore, I am a continuation of that process. So first is to have conversations with myself, with my family, with my circle. And, of course, I think the same extends to the media house I work in or I run. For example, we always speak about more women in the newsroom. Why? Because we need people with lived experiences to speak about…for example, there’s a huge difference in the kind of stories that are chosen and in the way stories are written by a woman editor and a male editor in a newsroom. The same applies if you have a Muslim in your newsroom. It’s very different when you have someone from the LGBTQ community, or from any caste-marginalised community, right? Everybody comes with their own lived experiences.

I did think around five years ago that just representation, as far as journalists are concerned, will help. But I’ve realised that lived experiences should not be translated into just that one journalist writing about that one subject. It has to impact the entire newsroom, which is these people should become the people that we go to [in order] to ask doubts. For example, I’m a Savarna. As an editor, I make it a point that everyone has to refer to these certain people in the newsroom who come with a lived experience and they can be the ones who advise the others, no matter their seniority. Newsrooms, I think, are changing that way. Unfortunately, changes happen when more calling out happens from within the organisation itself. Unfortunately, that’s the way things work. I wish it was a more positive change happening, but in whatever way, I just say, “Please let change happen.”

I feel that the people who are aware of the movements, the people who say they are anti-caste or they are against the caste system, they cannot keep learning forever.

I feel that the people who are aware of the movements, the people who say they are anti-caste or they are against the caste system, they cannot keep learning forever. They have to start reacting, right? Every time something goes wrong, people say, “I learned, I unlearned.” I don’t know how frustrating it must be for Christina, but I find it very frustrating. I just want to give a small example—I go to a lot of colleges for lectures, right? And, trust me, the most problematic thing is when we speak about affirmative action or reservation. Immediately, people will say, “But my merit goes away; I work very hard.” I remember in one popular Bangalore college I went to, the students were so agitated. It was a hall of 700-odd students, and many were agitated with this merit point. A professor stood up and he said that he is from a caste-marginalised community, and the entire auditorium was stunned because they never knew this. He had never spoken about this. He may have got triggered by the conversation. I felt very good that he spoke up, but then I also felt later—after I came back home—that is the onus only on him to speak up? Shouldn’t the other Savarna teachers have made interventions earlier or at that point? One of them had told me, “We are also still learning.” So, at what point are we going to stop learning and start acting? That’s the question we need to ask ourselves.

25.17

Smarinita: I’m going to move a little bit to the role of social media in this whole movement, because there are less gatekeepers on social media than there are in traditional media. So, we’re seeing caste-marginalised communities using it more, and using it more effectively. Christina, what role has that played to push some of this conversation, to push some of this thinking?

Christina: I think social media has been very significant in the last few years, particularly for caste-marginalised groups, right? And I do believe that it is going to be so for many years to come. I started becoming active on Twitter and on Facebook, particularly within this discourse, only about a few years ago. And it’s been a year or so since I’ve kind of stepped out. I do believe that social media can be extremely helpful for a whole lot of reasons. For example, we have so many Dalit women activists who are working on the ground, and who may not have access to media outlets that would readily pick up the stories that they are dealing with. The kind of atrocities that become big news are those that get reported or those that have in some way gained some kind of momentum in that particular place, but there’s a whole bunch of atrocities that we never get to hear about. And this news doesn’t ever get covered, even in local newspapers. In that sense, if they do have access to social media—in the language that they are comfortable in—they can always have an outlet to put stuff out. Not just reporting, but also analysis. And they also get to see other kinds of discourses that would come into play with respect to that particular atrocity or they may even be able to find very powerful allies who may take notice of what’s happening and help them in some way. Partnerships can happen, collaborations can happen. So, I think all of that has been great and when I work with Dalit Women Fight, this is something that we keep talking about time and time again, where they feel extremely glad that they have social media where they can put up stuff, particularly Twitter. But then again when it comes to discourses such as these, yes, of course, the number of caste-marginalised people, particularly Dalit people, on social media has definitely increased. Few years ago, when I was into it, I could probably just count the number of other Dalit women who were active, and I, yeah, I wouldn’t run out of one hand. But now there’s just a whole bunch of us on Instagram and on Twitter, and the kind of conversations people are having are so nuanced and rich. And it’s a delight to watch it because they’re all much younger and I see a bit of me in them. It’s sort of really nice to see that coming through, and I feel like it’s only going to get better and better and better.

I feel that even calling out requires a whole lot of labour, a whole lot of emotion, and I have participated in these only to realise that over a period of time, it erodes you as well.

However, and I take cognizance of what Dhanya mentioned just a while ago, that calling out is the only way forward in terms of change. I don’t agree with that entirely, because I feel that even calling out requires a whole lot of labour, a whole lot of emotion, and I have participated in these only to realise that over a period of time, it erodes you as well. Even as a caste-marginalised person, even as a Dalit woman, if I were to spend half of my time on social media just looking to identify the things that I’m going to be calling out because I feel it’s casteist, it’s not helping me in any way. Not just individually, even collectively. How is it helping my community? How is it helping our communities? Because, again, I’m seeing my community and myself at the centre of these movements. So if that were the case, then how is my healing going to happen? How’s my progress going to happen? How are we going to thrive if a significant time that I spend on social media is spent on calling out?

I feel that is still very Savarna-centric, that is still very upper-caste-centric, wherein I’m trying to tell people, “Hey, this is where you were wrong,” “That’s where you did not do it right,” and “This is okay, but this is still not okay.” It’s just a whole lot of labour that goes into it and a whole lot of emotion that I don’t think we must be spending so much on. So, I feel social media is helping and it is great, but it’s not necessarily only a good thing. I think there are some lessons for us to take from the experience that we’ve had in the last few years of how we’ve participated in anti-caste discourses and how we can make it better, and eventually get to a point where we are able to envision coalitions and we can use social media in a much more positive manner. Of course, it’s very utopic. But, nonetheless, I don’t think we are in a great place at the moment with the kind of calling out that is happening, which seems to take up so much more real estate than the issues that we really should be talking about.

Dhanya: I just want to make one point, Smarinita. So, I think the word I used—calling out—I was not restricting it to social media. I mean, I agree with what Christina said, it’s just so much of negative energy gone. The reason I said ‘call out’ is that Oxfam and Newslaundry have been doing this research, I think almost every year, where they look at the composition in newsrooms. So I believe that’s also [a form of] calling out. That research, which they do every year, where they call organisations and ask them, “Is your editor a Savarna?” or “How many people from marginalised communities do you have?” And when that report gets published, that’s also a call for action for the media houses to do something about it by next year, when that report or that survey is done again. So, Christina, I just wanted to say that when I say ‘calling out’, I also mean a lot of action wherein media houses are told, “Look, this is what is going wrong.” Any kind of organisation, for example, corporates, where is our study on the composition of our corporate world? Especially, like you said, who are the CEOs? Are there any people from marginalised communities? We don’t really know, right? And I know that even when Newslaundry and Oxfam does that research, most news organisations do not even reply to them. Now, how problematic is that? That you do not feel obliged to even reply.

Therefore, that calling out has to come in various ways, and I don’t think it should come from the community itself because that can be really draining, right? It really has to be in other ways. And we have to keep thinking of the ways to do it. I think if it’s a media [entity], it should come from within the media. If it’s a corporate sector [entity], it has to come from within the sector. There are so many ways to do it, I feel. So, we have to just strategise.

32.04

Smarinita: Like Dhanya you were saying, the numbers have actually become worse this year than the last. So even some of that calling out doesn’t lead to change. Caste-marginalised communities fighting is not a new fight in the sense that there have been fights for women’s rights, there’s the Black Lives Matter movement. Is there stuff that we can learn from other places?

Christina: Yes and no. I do believe that we need to come up with strategies that are very specific to our context. I think our context is fairly complicated, because we have a whole bunch of intersectionalities that we are playing with, and we keep seeing these. Every time we have a nuanced conversation, there will be an equally nuanced opposing conversation that will seem to have very equivalent merit to what we are saying. And so I think we need to come up with more workable strategies. Having said that, one example that I can give is within the corporate space. I am in so much admiration of the queer movement, which has done such great stuff within the Indian corporate space. To the extent that today we have actual policy changes that have happened within organisations, such as medical insurance for same-sex partners and being able to provide assistance for surgeries. A whole spectrum of policy changes has happened or teams within these companies are fighting for such policy changes. And people have been receptive and accepting. They’ve been very willing to rethink the way they’re looking at it. Organisations have made it a point to include in their codes of conduct that you should never say anything that is queerphobic, homophobic, or transphobic. I feel those are huge milestones that the queer movement in India has achieved as far as the corporate space is concerned.

But we have not been able to make any such—not even comparable—headway as far as the anti-caste space is concerned. Of course, the reason is not just whether we are good at our strategies or not; it has so much more to do with the fact that the people who are sitting on the other side, who happen to be mostly upper caste, may happen to have queer people in their family and friend circles, but may not have caste-marginalised people in their family or friend circles. So that makes it more difficult for them to even look at it as an issue. But I think there’s definitely something for us to learn from the way in which they have designed campaigns. They have just gone at it with a lot of courage and with a lot of gumption.

Call-outs and cancelling and all of that is good, but it has its own limitations.

And I think that’s something we can definitely take out of, not just in terms of adopting practices, but also in terms of partnerships and in terms of collaboration. So, what kind of partnerships can the anti-caste movement have with the queer movement? Because there are a whole lot of us who are both queer and Dalit. How do we bring all of us together and really kind of work together? And the same thing goes for the feminist movement as well. None of us are leading single identity lives. We are all part feminist, part queer, and part whatever, right? So, I think it’s not just about adopting practices, but also about learning from each other in a very cohesive, collaborative manner. And, again, going back to my earlier point, I think call-outs and cancelling and all of that is good, but it has its own limitations. It should not take up so much space that it becomes detrimental for us to envision and imagine coalitions and progress that we can achieve if we were to just work together.

36.01

Smarinita: What’s the progress in the movement that you would like to see? Because both of you mentioned that it’s a long journey, it’s an arduous journey, and there all of these factors. But what would keep you going?

Dhanya: So, before going to the question, I just want to address one thing that Christina said. All credit to the queer moment for whatever they’ve achieved in India, not just in the corporate space, but even so many governments have made policies which are queer friendly, or they have committees, etc. But just thinking from the other side, I also believe that’s a much easier thing to do for corporates or governments because you’re still othering them. As in, if you are talking about anti-caste policies within organisations or the government, it impacts everybody in the sense that the people making the decisions are mostly from oppressor castes, which is why the changes are not happening as much as we would want them to happen, unlike what the queer movement has been able to do. And I don’t think it’s going to be as easy, but I hope that with time, if we can convince more people that this is the right way forward, then it may happen.

If young people are made aware of their privileges and the lack of privileges of other people, it really makes the journey much easier.

As far as envisaging a future is concerned, at least personally, I believe we should speak to the younger generation more. While we keep having these conversations, which are negative or positive, or like Christina said, we need to build coalitions, we need to figure out how to make people more responsible, how to make companies, government, etc. more responsible. But I think, alongside all that, we need to speak to our younger generations. At least as the mother of a 10-year-old and as someone who visits schools and colleges to speak, I feel that if young people are made aware of their privileges and the lack of privileges of other people, it really makes the journey much easier than trying to convince them when they’re 30 years old and tweeting away. We should have more literature around that. I mean, there are books which are now explaining the caste movement, Ambedkar’s vision, etc. for children. So in small, small things, I think we need to introduce those changes. It’s only when we take the young along with us that we can truly make changes. I mean, the rest of it is a fight, right? You fight against governments, you fight against corporates, you convince them to change policies. And I think the language that we use, for example, using the word ‘reservation’ itself…we have to watch our language, especially around the young. When we convince our young people, when we tell them about their privileges, and they grow with an understanding of that, I think we will be able to bring more change in. Or maybe I’m too optimistic, but I just want to end on an optimistic note.

Christina: I obviously do not want to go super optimistic and say that I want everyone to be fully conscious of what’s happening and all of that. I do hope that happens, but I am fairly sure that’s not going to happen in my lifetime because it’s just that big of a monster to tackle, right? Having said that, I envision a future where Dalit women and Dalit queer people, where Dalit people in general, are able to lead full lives that they were denied for thousands and thousands of years. I envision a future where they are able not to just do things, but also to dream, be happy, and laugh, and not necessarily be burdened with this political identity. It is a political identity because it has been politicised, as it has been a marginalised identity for so long. But I envision a time when they can completely shirk off this burden and just be themselves, just be us—whatever that means. Not just in terms of professions, but also in terms of being able to experience a whole spectrum of emotions, a whole set of experiences—whether it’s love, lust, joy, faith, or healing and spirituality. As human beings, we are capable of a whole bunch of things, and we can dream, we can want, and we can desire. But right now, I don’t think a lot of us…I don’t think even a few of us are allowed to experience that, simply because we cannot afford to. We have to think about food, shelter, and clothing. We are still at the base of the Maslow’s triangle, and I just want a future where my people can be their full selves.

40.53

Smarinita: That is such an evocative and hope-filled message, Christina. Thank you. I’m taking back so much from today’s conversation. But, most importantly, what I think all of us need to understand about allyship is that it doesn’t necessarily involve the passing of any kind of mic. Instead, it involves collaboration, coalition, and partnership. And while affirmative action and formal routes to ensure representation for caste-marginalised people are important, it’s time to go deeper.

We need to move beyond tokenistic allyship and get to a place where caste-marginalised communities can occupy centre stage, drive the change, and craft their own narratives.

Thank you, Christina and Dhanya, for driving this really important conversation.

—

Read more

1. The politics of mental health and well-being

2. “I want to build a better life for those around me”

3. 5 ways to be an anti-caste ally without savarna saviour complex

4. Caste, friendship and solidarity

5. How caste oppression is institutionalised in India’s sanitation jobs