IDR had the opportunity to meet with Anil Swarup, Education Secretary at the Ministry of Human Resource Development. In this interview, he talks about his ideas on what needs to change in education, and how civil society and government can work together make that change happen.

Below are highlights.

The first 100 days: “The solutions are here.”

When I took over as Secretary of Education, I received plenty of advice on how education should be managed in this country. My counter to them was, if the advice were as simple as they were making it out to be, why hadn’t things changed on the ground in all these years?

Tragically we have been looking for solutions in Iceland, Scotland, England, Holland, and Finland; but not in the homeland. So I thought I might as well see what was happening here, and that’s what triggered the idea of travelling to over 20 states in the first few months to discover what the problems were. And to my amazement, I found solutions.

[quote]Instead of importing solutions, we should look to Indian examples. The solutions are here.[/quote]

I saw that the government and nonprofits, on their own or working in tandem, were doing great work and had come up with solutions to a large number of problems. So I came back excited, and resolved that instead of importing solutions–many of which come from alien contexts and require piloting to see what works here–we should look to Indian examples. The solutions are here.

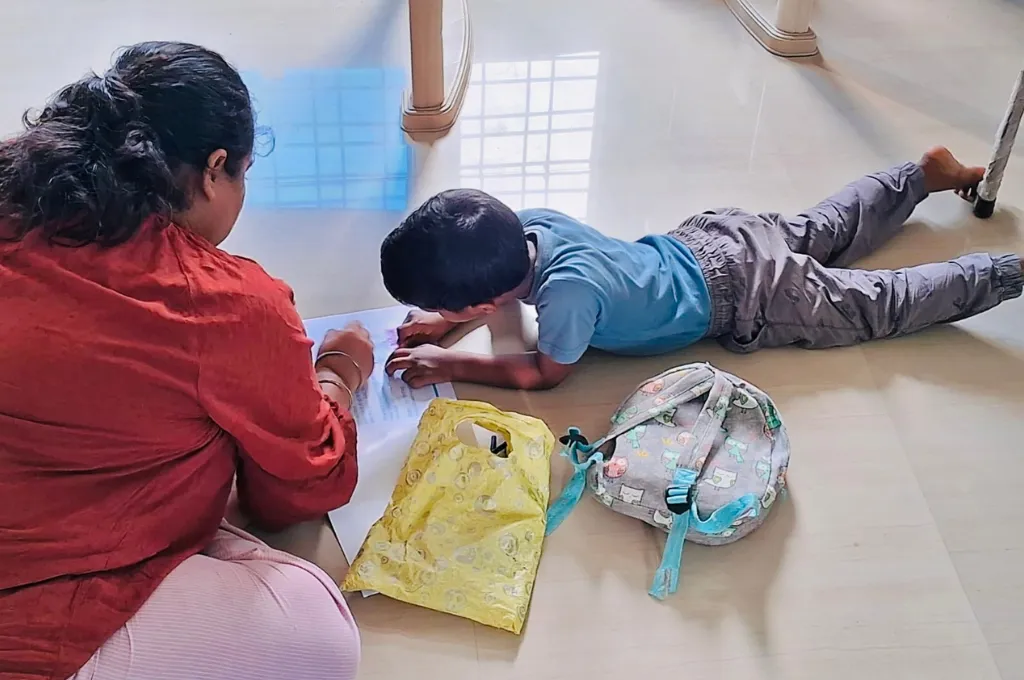

Photo Courtesy: Charlotte Anderson Photography

“A sharp focus on the teacher value-chain will change how education happens in India.”

Teachers are pivotal to the education system. Though I had heard this from advisers and also experienced this during my travels, discussing it with experts in the education space confirmed that the right way forward would be to set this value-chain right.

We are looking at the entire continuum of a teacher’s role–from introducing rigorous pre-service training, skills testing and regular in-service training, to addressing issues related to absenteeism, administrative responsibilities and quality of teaching.

Over the next 4-5 months, we will put an end to the rampant frauds in B.Ed colleges. NCTE has already sought affidavits from them, and the 40 percent that haven’t responded will soon lose their affiliation.

In addition, we are putting in place a system to assess the quality of pre-service training at these colleges. In order to help students evaluate these colleges, we have hired a third-party agency, Quality Council of India, to rate them.

We are also looking at introducing a CAT- or SAT-like examination for entry into the teaching profession and a detailed induction programme for new teachers.

[quote]An idea is worth its salt if it is politically acceptable, socially desirable, technologically feasible, financially viable and administratively doable.[/quote]

Absenteeism is a big problem among teachers, with 25-28% not showing up for work. Understanding the context is critical to finding a solution to this phenomenon. In Kerala, for instance, teachers can’t afford not to go to school; they will be lynched. In Uttar Pradesh however, teachers consider it their right to remain absent at will: some of them participate in local politics and it is quite common for them to seek transfers to schools located close to their political work. Their primary interest in politics, rather than in teaching, contributes to the absenteeism in UP schools.

We therefore proposed that once a teacher is assigned to a school,s/he can be transferred only in the case of a promotion–similar to the system followed by the civil services.

Administrative burden is the other reason for absenteeism. For example, teachers have to send detailed hand-written administrative reports to the government. Going forward, all requirements will be housed in a tablet, through which documentation can be uploaded once every two weeks. Such measures will reduce the teachers’ drudgery. Additionally, these tablets will mark biometric attendance of teachers and feature training videos to up-skill them.

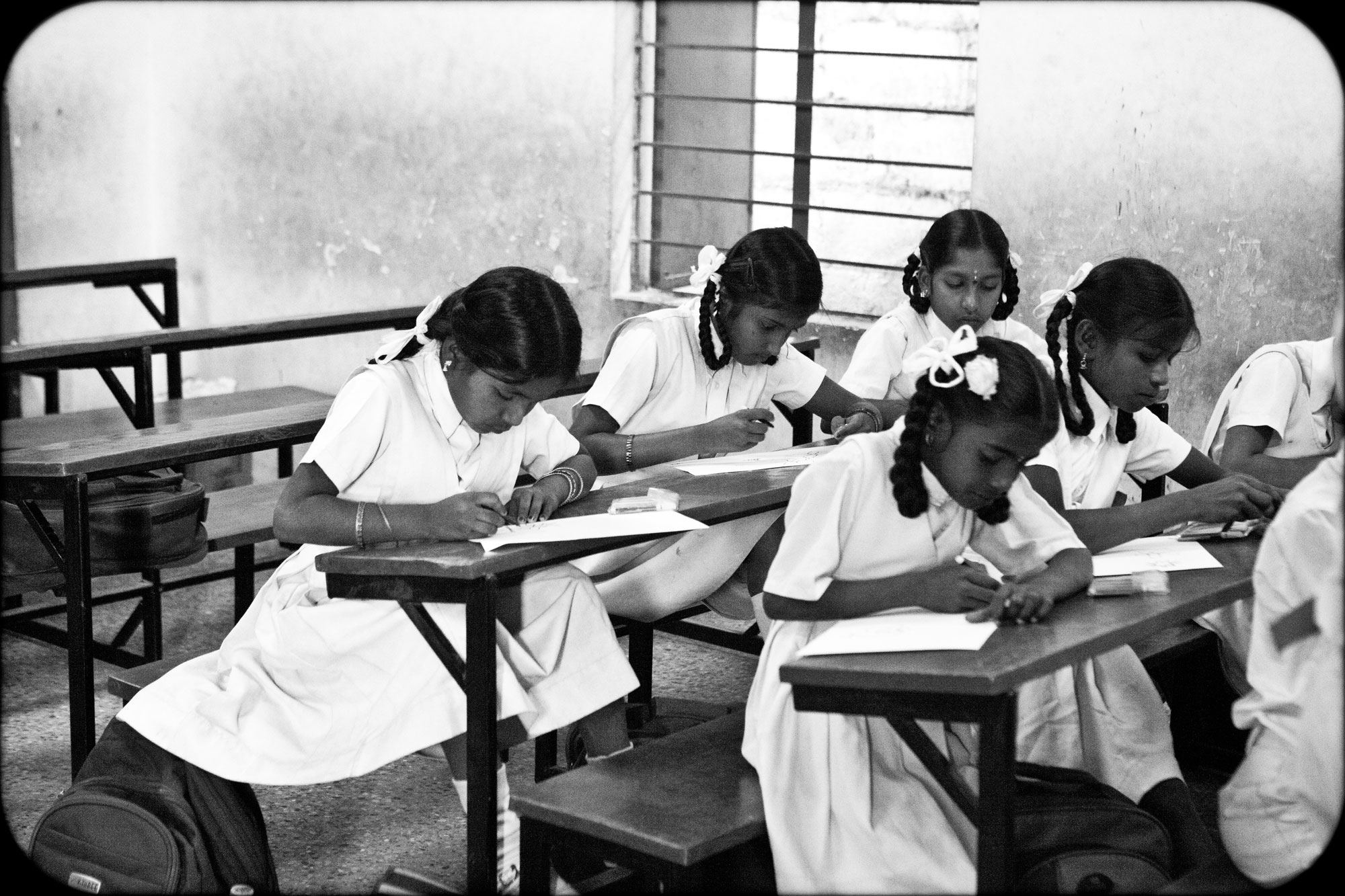

Photo Courtesy: Charlotte Anderson Photography

“My idea was to create a platform that facilitated greater collaboration between civil society and the government.”

After having identified teachers as a key part of the solution, we held intensive workshops with more than a hundred nonprofits to understand what they were doing in the field of education, how they could scale their work, and what support they needed from the state and central governments.

Given the number of successful examples from across the country, we realized that we don’t really need to run pilot programmes before scaling. Pilots often involve huge resources because the objective is to prove the model. Such resources, however, are seldom available when scaling. An idea is worth its salt if it is politically acceptable, socially desirable, technologically feasible, financially viable and administratively doable.

[quote]The government does not expect the nonprofits to scale dramatically.[/quote]

We had seen solutions on the ground that met these conditions; all we had to do was give states an opportunity to choose the ones they considered feasible.

So I asked the nonprofits to draft MoUs. It was at this point that we thought of holding regional workshops, where we could road-show the nonprofits’ work and these MOUs, and generate interest within state governments for these solutions.

After these workshops, we are planning more detailed state-level workshops with nonprofits to enable more buy-in across stakeholders.

We are also launching a portal in a few months, which will serve as a ‘marriage bureau’ for nonprofits and states. It will list the gaps identified by the states, what nonprofits have to offer, and also enable them to negotiate on the platform.

When partnerships with the nonprofits do materialise, the government does not expect them to scale dramatically. The nonprofits might choose to expand from three districts to four–it is entirely their call. Ultimately, the goal is that the government funds the programme and takes over.

This has already started happening. For example, Akshara Foundation has been working in Karnataka. They just signed an MoU for expansion into Orissa, funded fully by the state government.

Photo Courtesy: Charlotte Anderson Photography

“The results will begin to show this year.”

Implementation of these plans will happen this year. Intermediate outputs will be visible within this timeframe, while long-term outcomes will take some time.

[quote]Scale will never come from private sector and quality will never come from the government.[/quote]

From August 1, we are introducing GPS-enabled tablets in schools in Chhattisgarh These will perform a number of functions, including taking biometric attendance of teachers. We will review progress in three months and, by December 31, we will have taken a decision on whether to launch this programme in other states. Similarly, we are launching a national digital platform for teachers in July and will monitor its performance.

Intermediate outputs will be visible within the year. Some of the outcomes (such as the impact of the action taken to regulate B.Ed colleges) are longer term, but much of the implementation will take place this year. We will use technology for real-time monitoring of progress and to help identify and correct any department inefficiencies.

“There are always limitations with implementation.”

The fundamental limitation is attitude. You have to make people believe that alternative scenarios are possible,even if little has changed in the past. By showcasing what is already working, the ideas become more scaleable.

Existing institutions within the system also inhibit the flow of ideas and new approaches.

For example, aanganwadis are integrated with schooling in Rajasthan, but not in other states. The absence of this essential integration creates constraints with implementation and outcomes. There are also always limitations around finance and human resources.

“I view the role of the private sector as being primarily one of financial and technological support.”

Companies can participate in the education sector by using their CSR funds and providing technological support. With the kind of coordinated effort we are now seeing in education, companies can fund projects that fit within a larger purpose, one that is aligned with national priorities.

They will derive comfort from the fact that progress is being monitored, and due diligence has been carried out on the nonprofit partners. This is a marked difference from companies supporting a number of small initiatives scattered across different locations and which might have limited impact.