This article is part of Failure Files, a special series conceived by India Development Review in partnership with Acumen Academy, where social change leaders chronicle their failures and lessons learnt.

It was the year 2014. As Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellows, we were working with the local district administration in Jamui district, Bihar to improve learning opportunities for students of three residential schools. Our experience of working with government schools over the past two years had reinforced our belief that teachers were simply a resource in the school system; and an easily replaceable one at that.

The answers lie in technology, or so we thought

Our initial belief was that educational technology (EdTech) was the solution, and would work independently of the teacher’s role in ensuring quality education to the students. We saw both the teacher and the tech simply as platforms for disseminating information. So, we designed our programme based on these assumptions. The two were compared on metrics such as the quantity, quality, and delivery of information, and on the way in which a student might benefit from the design advantage that technology offers—variety in type and use of content. For instance, ‘What information should I watch?’ (type of content), and ‘How should I engage with the information?’ (use).

We pitched this idea to our friends, and though many of them were skeptical, they donated 60 tablets to us. Once the tablets were in place, we searched and partnered with a quality content provider, who provided us content free of cost. Next, we mapped the content with the state government’s syllabus, created groups of students who would be using them, installed apps that would monitor content use, and placed these tablets in three government residential schools. This intervention was designed based on our initial hypothesis that an EdTech platform will function independent of the teacher’s participation, as we thought factors associated with teachers (quality of instruction, lack of interest, absenteeism) were the major reasons that learning was not happening.

However, once the initial euphoria and the real work set in, we started to realise that our intervention had several loopholes. This resulted in almost 50 percent of the tablets breaking in the first four months of the intervention, and the EdTech platform being used poorly by the students. Our learning from this intervention made us realise how our assumptions stopped us from considering what we now see as the five fundamental pillars of designing an EdTech intervention.

The idea was to use technology as a platform for disseminating information which would be of a better quality, and would therefore help overcome the limitations of a teacher and the boredom of a textbook. We thought this would give students a chance to learn better, and at their own pace. However, we failed to realise that information is not knowledge. For information to become knowledge and be valued by the child, it has to go through processes of reasoning, dialogue, questioning, and sharing. A teacher, not technology, is best placed to facilitate this.

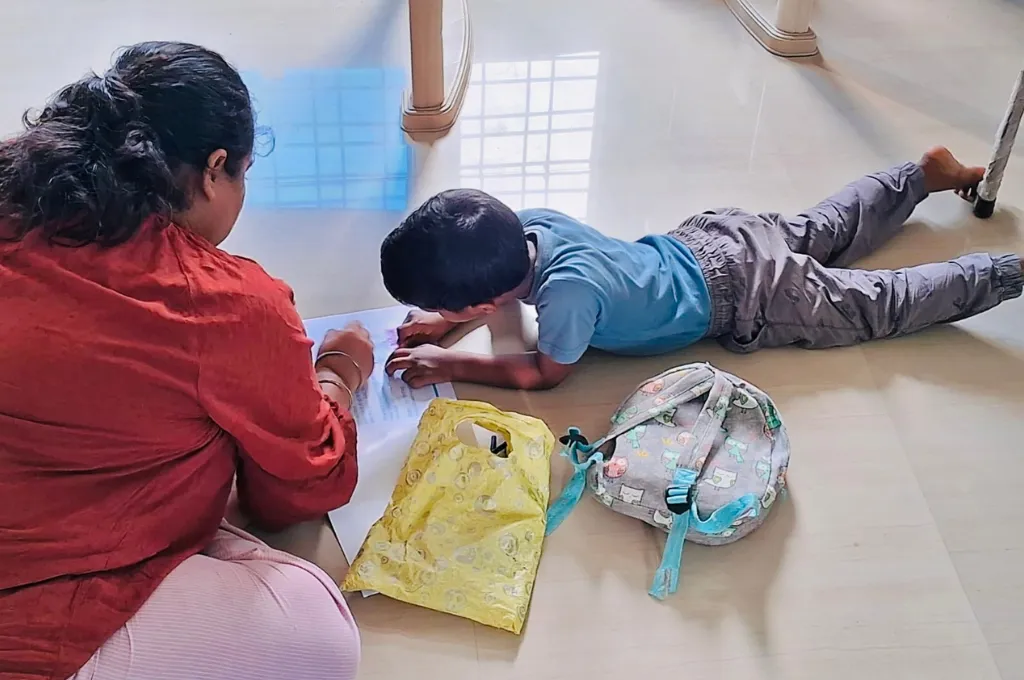

Our intervention was built around the idea that a group of five students would share and learn from one tablet. These students were grouped based on their grades, and we assumed that since they shared common spaces, they would be more likely to support one another. This assumption turned out to be wrong. We realised that until a strong common identity, shared purpose, and regular reinforcement of values are built in, merely bringing people together and forming a group doesn’t lead to accountability.

Merely bringing people together and forming a group doesn’t lead to accountability. | Picture courtesy: Ajaya Behera/Gram Vikas

One of the central ideas of the intervention was that giving tablets to a group of students will ensure agency to all members of the group. This, however, was not how things panned out. In many groups, we found that certain members had emerged as decision makers, and they would decide what content would be watched, when, and how. This created a hierarchy within the group.

While we measured access to tablets at a group level, we ignored lack of access within these groups. We also ignored the importance of reinforcing the common purpose. What we failed to do was envision the influence a peer group leader could have and think of ways to identify and engage them in the intervention.

Our intervention was focused on the platform and content, and all our energy was spent putting a tempered glass and a leather cover for protection, coding, and adding quality content to the tablets. We paid very little attention to understand our EdTech intervention as a system, with many components linked to each other.

We failed to ask, for instance: How many charging points were there in the schools? For how many hours did the school get electricity? What were the voltage fluctuations? How could we link speakers and audio splitters, which were necessary for some aspects of the content? This ignorance led to many of the tablets becoming dysfunctional within a short period, mainly due to high voltage fluctuations and using very poor-quality chargers to charge the tablets.

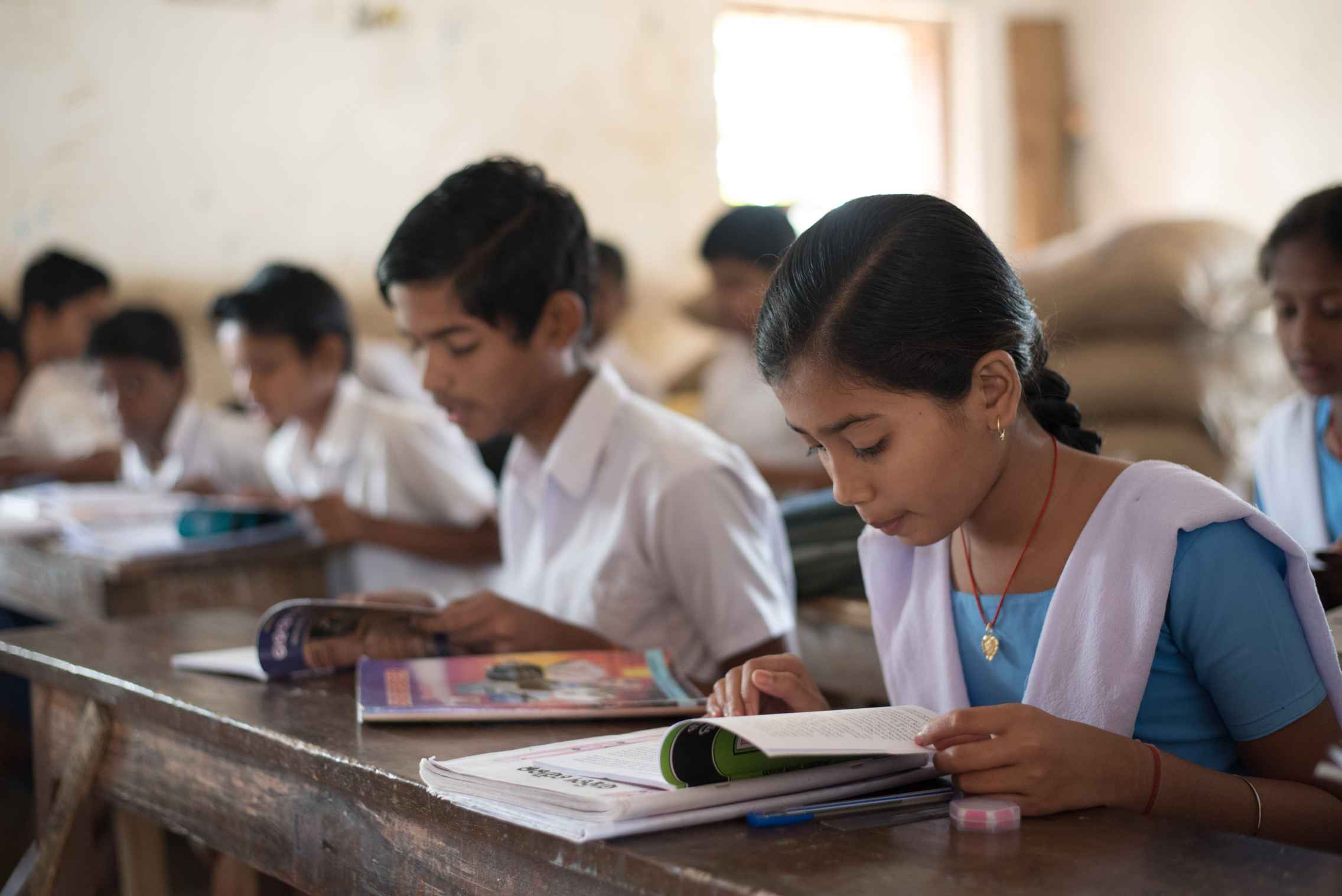

Throughout our intervention, we ignored the role of a teacher, believing we could circumvent them and link students to what mattered the most—a good content platform. This was our biggest failure. We failed to build on the possibility of bringing teachers and technology together. Doing so would have allowed the teacher to use EdTech as a powerful tool to expand their capabilities, and envision a learning ecosystem that breaks the limitation of textbooks or other resource constraints, creating endless possibilities.

We believe the power of EdTech lies in creating and expanding these possibilities, not only for the students or the teacher, but for all stakeholders. This is possible only when stakeholders have a stake and a voice in the intervention design.