Over the last 70 years, India has made significant progress when it comes to women’s empowerment. We have seen the growth of self-help groups across the country, an increase in women’s access to education, and a reduction in child marriages, among other things. Despite these steps in the right direction, a number of gender disparities—from increasing violence against women to women’s falling labour force participation rate—continue to exist. Addressing these requires us to engage with patriarchy, the underlying system that continues to privilege men, usually at the expense of women.

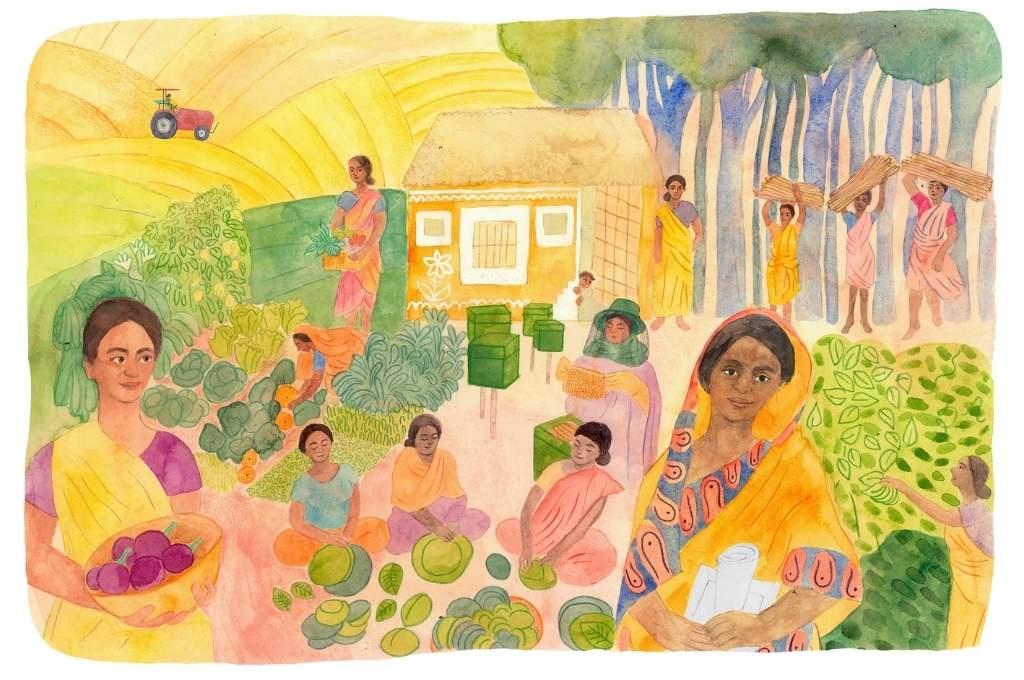

In rural India, land plays an important role in the lives of women, who are highly dependent on it for their livelihoods. Even though only men are officially recognised as farmers, more than 80 percent of the labour on farms is done by women—either by women from the family or by hired labour. Yet, only 13 percent of agricultural land is owned by women. A similar scenario plays out with regard to forest land. Women do most of the work when it comes to collecting forest produce, but selling it and deciding what to do with the money remains the domain of men. To make women in rural India more independent and self-reliant, it is important that we engage with the issue of land rights.

When women own and control land, it has a positive impact on society

Land is an asset that gives women financial security, shelter, income, and livelihood opportunities. Therefore, land rights for women should be seen as a means to drive progressive and sustainable change among women, their families, and communities, rather than as an end in itself. While there is limited data on this in the Indian context, global research shows that when women own, manage, and cultivate their own land, it has a multidimensional impact.

1. It provides women financial security

Global studies show that women with strong property and inheritance rights earn up to 3.8 times more income and have 35 percent more savings than those without. This is because they can productively use land as a source of livelihood and have more say in financial decisions related to the income generated from it.

2. It enhances women’s social agency

When women own land, they begin to be recognised as decision makers within the community. The power to decide what crop to grow, where to sell it, and what to do with the money instils confidence in them and strengthens their role in society. This can lead to increased engagement of women in governance—be it voting, active participation in local politics, or standing for panchayat elections.

3. It improves outcomes for their families

When women have control over land, agricultural production increases, leading to higher food security for their family. This is because women have a greater incentive to invest in increasing the productivity of their farms, as they feel more confident about the returns it can generate. Similarly, women’s land ownership is directly linked to better health and educational outcomes for their children. When women earn more, they invest a greater amount in the upbringing of their children as compared to men. Children of women with land rights are also less likely to be pushed into child labour. Lastly, when women earn more, they also spend more on healthcare for their family, leading to improved health outcomes.

4. It protects the environment

Women are known to be better nurturers of land and forests as compared to men. They are typically more inclined towards crops that contribute to family health and nutrition and are more attuned to customary traditions and knowledge—be it about local crops, the kind of trees to grow, or stewarding the forest. They also tend to focus more on regenerative crops or food security crops that are environmentally friendly instead of cash crops, thereby reducing soil degradation and maintaining biodiversity.

The land rights landscape in India

It’s no secret that the overall land rights landscape in India is extremely complex, with many factors—from religion to type of land and state revenue laws—determining who can access and control land. To ascertain whether a woman can or cannot own a piece of land, there are two sets of factors that come into play. The first relates to the type of land, that is, whether it is farmland, forest land, or pasture land, if it can be owned individually, jointly, or by the community, among others. The second set relates to the status of the woman, that is, her religion and whether she is single, married, widowed, or divorced, and other such factors.

While there are many such laws, policies, and interventions, women land ownership is majorly influenced by two laws:

1. The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act 2005, which gives a daughter equal rights to the property of her parents. This is a particularly important provision, given that almost 80 percent of farmland gets passed down through inheritance.

2. The Forest Rights Act 2006, which recognises the rights of forest-dwelling communities to forest land and resources. Under this act, women can be joint owners of land along with men when applying for individual forest rights, as well as collectively own land with their community under the provisions for community forest rights.

What’s interesting to note here is that the broader legal framework around land rights in India is gender friendly, largely driven by a lot of work done by activists, lawyers, and experts over the last 20 years. In fact, according to a World Bank report, from a legal perspective, India falls into the 80th percentile. These are necessary initial steps, but not sufficient on their own.

So, what prevents rural women from owning land?

Despite laws being broadly gender equal, there are significant barriers to implementing them. The first major barrier is the pervasiveness of a patriarchal mindset throughout the system. Women themselves, their families, their communities, and even government officials are often of the opinion that land matters are the domain of men. This deters women from asking for their right and men from recognising women’s equal claim to land.

A large percentage of land in India is owned and controlled by the upper castes.

Another barrier is the perception of land rights as a complex issue due to many intersecting laws based on religion, marital status, and type of land, among other factors. This acts as a barrier not only for women, but also for funders and civil society organisations looking to engage in land rights work. To further complicate this, the market is extremely unorganised, with limited data, numerous information gaps, and a lack of awareness, capabilities, and resources across stakeholder groups.

Lastly, land is also a socially and politically sensitive issue, especially when you layer it with the caste system. A large percentage of land in India is owned and controlled by the upper castes. These are the people who are active in politics, sitting on panchayat sabhas and in other positions of power. This makes it all the more difficult for women, especially those from Adivasi or caste-marginalised communities, to access their rights.

Funders need to start investing in women’s land rights

In the face of all these roadblocks, what works in the favour of organisations focused on land rights is that the importance of land is not lost on women. We’ve seen that there is an inherent understanding among women that having land rights will strengthen their role in society, giving them financial security and their children a better life.

For funders looking at the long-term sustainability of their work on women’s empowerment, investing in women’s land rights is one way of making sure that they will have more agency even years after a particular programme or project has ended. This also holds true for funders working on issues that sit at the periphery of land rights—agriculture, livelihoods, or health—since access to land is often at the root of many issues. Here are four ways in which funders can get started on their journey.

1. Spend time understanding land

This is one of the most important things anyone looking to work in the land rights space needs to do. The perception of land as a complex and sensitive issue often stops funders from looking at it as a feasible pathway to change. But, as funders, it’s time we start taking risks and investing in the difficult work of changing structures and systems—work where there may not be guaranteed outcomes.

As part of this journey of understanding land, it’s important that we don’t look at it as a vertical within programmes and organisations. Land is often a difficult topic to talk about; it’s not something that can be worked on overnight. Organisations working in this space need to have a strong presence within the community and understand the context in which they’re working, because it’s very easy for these conversations to go south. So unless you’re funding organisations that are explicitly working on land rights, think of land rights as a ‘horizontal’ capability that cuts across work in rural development, livelihoods, or women empowerment.

2. Invest in on-ground implementation

Working on ensuring the proper implementation of existing laws and regulations can be a good pathway for funders to enter the land rights space. Beyond the Hindu Succession Act and the Forest Rights Act—both of which focus on land ownership—there are numerous policies and schemes that provide additional benefits to households where women are co-owners of the property. In Maharashtra, for example, under the Laxmi Mukti Yojna, if a woman’s name is on the patta (record of land rights) and the landholding is more than two acres, the government will recognise two farmers working on the land and provide double the benefits for seeds, fertilisers, and other agricultural inputs. Implementing schemes such as these, which leverage land rights as a means to other ends, is a good starting point.

3. Fund data and research in the land rights space

Another important gap that funders can start addressing in the land rights space is building knowledge and evidence, as these are almost a prerequisite for highlighting the quantum and size of issues. While India’s data ecosystem on land-related information is quite rich, the many databases differ on women’s land rights reporting parameters, thus giving conflicting information for both policy and practice.

Additionally, a designated gender column is still missing in India’s land records in most states. Funders need to invest in programmatic evidence generation as well as ecosystem-level research initiatives to strengthen evidence and create alignment. This can then be used to build narratives and deepen work in the land rights space.

4. Engage with government

One of the most difficult, and important, areas of work is changing the deeply patriarchal mindset of government systems. Funders who have deep relationships with government can focus on investing in making sure that officials at all levels—from ministers to patwaris, district collectors, and revenue officials—understand the laws and are sensitised to the need for women’s land rights.

—

Know more

- Read this series that delves into the various aspects of women’s land rights in India.

- Explore more evidence and data on the links between land ownership and women’s empowerment in India.

- Learn more about the reforms needed in India’s land policy to bring about an agricultural transformation.

Do more

- To learn more about her work, connect with the author via LinkedIn or drop her an email at shivani@womanity.org