Imagine this scenario: Ramu, a farmer from a small village in central India, discovers a few old, valuable coins while ploughing his fields. Delighted, he sells the coins for a paltry sum of INR 1,500. But this jubilance is short-lived, as he soon receives news that he is being prosecuted under the Indian Treasure Trove Act, 1878, for failing to report the discovery of the ‘treasure’ to the district authorities. He now faces the possibility of imprisonment for up to one year.

This obscure and outdated law is one of many with the potential to turn ordinary citizens into criminals. In fact, there are more than 6,000 offences under union laws alone—enough to put nearly anyone at risk of jail. This over-reliance on criminal law—often driven by subjective notions of public order and morality—and the criminalisation of trivial infractions point to a deeper issue: the absence of a clear policy framework guiding when and how criminal laws should be applied.

This lack of clarity has allowed for the politicisation of criminal law, making it a convenient, almost default response to governance challenges (such as ensuring regulatory compliances) that could otherwise be managed through civil actions (such as the imposition of monetary penalties). The continued reliance on criminal law to manage the citizen–state relationship is incompatible with the constitutional values of freedom, justice, and liberty in a modern, democratic India.

From deterring crime to governance

Given its power to deny individuals their life and liberty, criminal law becomes a potent tool in the hands of the state, particularly in maintaining public order. Traditionally, criminal law has focused on protecting life, liberty, property, public order, and state security by proscribing and punishing conduct that harms any of these. The Indian Penal Code, 1860, along with many other special laws enacted post-Independence, followed this approach. Despite the enactment of new laws over the past decades, the underlying notions guiding the use of criminal law have remained relatively consistent.1 These principles include protecting the fundamental values vital to society and its political establishment, ensuring that constitutionally protected rights are not criminalised,2 and rationalising punishments to align with the goal of safeguarding these values.

However, there have always been aberrations. Since colonial times, criminal laws such as sedition and defamation have frequently been used as instruments to suppress dissent and stifle political and social movements, including the Indian Independence Movement. Similarly, Victorian morality was imposed on Indians by criminalising same-sex relations and adultery, until the Supreme Court recently struck these laws down. The criminalisation of begging and drug use also reflects an over-reliance on criminal law to address deeply rooted social issues, indicating that governmental responses often lack nuance and thoughtful consideration.

Regulating everyday behaviours

The above examples are, however, only the tip of the iceberg. There is a growing trend of using criminal provisions for regulating a wide range of behaviours, even those that may not pose a significant threat to societal order, life, property, or state security. In fact, criminal law has become central to everyday governance in India.

For instance, simple regulatory non-compliances—such as failing to fulfil registration formalities, not maintaining or failing to deliver books of accounts, failing to exercise a pet properly, obstructing an officer in the exercise of their power, or jumping a red light—can all lead to jail time. In fact, at least 14 union laws criminalise the failure to maintain or produce books of accounts, with punishments including imprisonment up to two years. Similarly, more than 20 union laws criminalise obstruction of any authority in the exercise of their power, often without clearly defining what constitutes obstruction, leading to jail terms and fines.

Even though the intent behind criminalising these non-compliances is to ensure strict adherence to rules, it raises a fundamental question: Is criminal law the right tool for this purpose? Can a legal framework designed to respond to heinous crimes such as murder and rape also be used to ensure timely submission of paperwork, or that sweepers give proper notice before taking a leave, or that no one drives an uninsured vehicle? By blurring the line between serious crimes and minor infractions, this approach not only stretches the role of criminal law and criminal justice functionaries but also undermines the core function of the criminal justice system. Criminal law should be reserved for grave offences—those that pose a significant threat to human lives, property, or the socio-political order. Applying the same response to minor contraventions and failing to distinguish the severity of violations undermines the fundamental purpose of criminal law.

Moreover, this approach fosters a culture where punishment and deterrence are seen as the primary methods for ensuring compliance with laws. Relying on criminal law to address minor non-compliances reinforces a system that is not only excessively harsh but also ill-suited to modern democratic societies, where punitive measures are increasingly being replaced by restorative justice. It is also misaligned with contemporary citizen–state relations, which emphasise strengthening this relationship through education, incentives, and social engagement rather than enforcing compliance through criminalisation.

Lacking clear objectives and rationale

The arbitrary use of criminal law does not stop at excessive criminalisation. The issue is complicated by inconsistency and irrationality in prescribing punishments. Going back to the example of Ramu—he faces up to one year of imprisonment for failing to disclose the discovery of treasure. Ironically, the same jail term is prescribed for offences such as sexual harassment by ‘making sexually coloured remarks’ or forcing someone to work against their will.

India’s criminal law landscape is rife with examples of vastly different crimes being punished similarly, or conversely, similar offences being punished differently. For instance, defamation carries a punishment of imprisonment up to two years, the same as the punishment for the concealment of birth by secretly disposing of a dead body. Similarly, making false statements on oath attracts the same punishment—imprisonment for up to three years—as subjecting a woman to cruelty. On the other hand, obstructing a public officer attracts varied punishments across different laws: a fine of up to INR 200 under the Merchant Shipping Act, 1958; imprisonment for up to three years under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940; and imprisonment for up to three months under the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006.

Although the duration of imprisonment is supposed to reflect the gravity of the offence—the more serious the crime, the harsher the sentence—there are glaring inconsistencies. For example, while assault or criminal force without grave provocation is punishable with imprisonment for up to three months, rescuing cattle from the pound is punishable with imprisonment for up to six months.

For a country that relies so heavily on criminal law for matters of day-to-day governance, there is a troubling lack of coherence in determining which crimes merit what punishment. This inconsistency stems, perhaps, from a lack of clarity regarding the purpose of punishment itself. For instance, what outcome does a one-year prison sentence aim to accomplish for a convict who failed to disclose the discovery of treasure, compared to someone who has sexually harassed a person? In the same way, can failing to file a property tax return on time truly be compared to subjecting a woman to cruelty, both of which carry a prison term of up to three years? These offences are vastly different in nature, yet the law treats them similarly. For punishment to be effective as well as reformative and not just deterrent, the state should adopt distinct approaches for individuals convicted of such disparate crimes.

Recent attempts at change

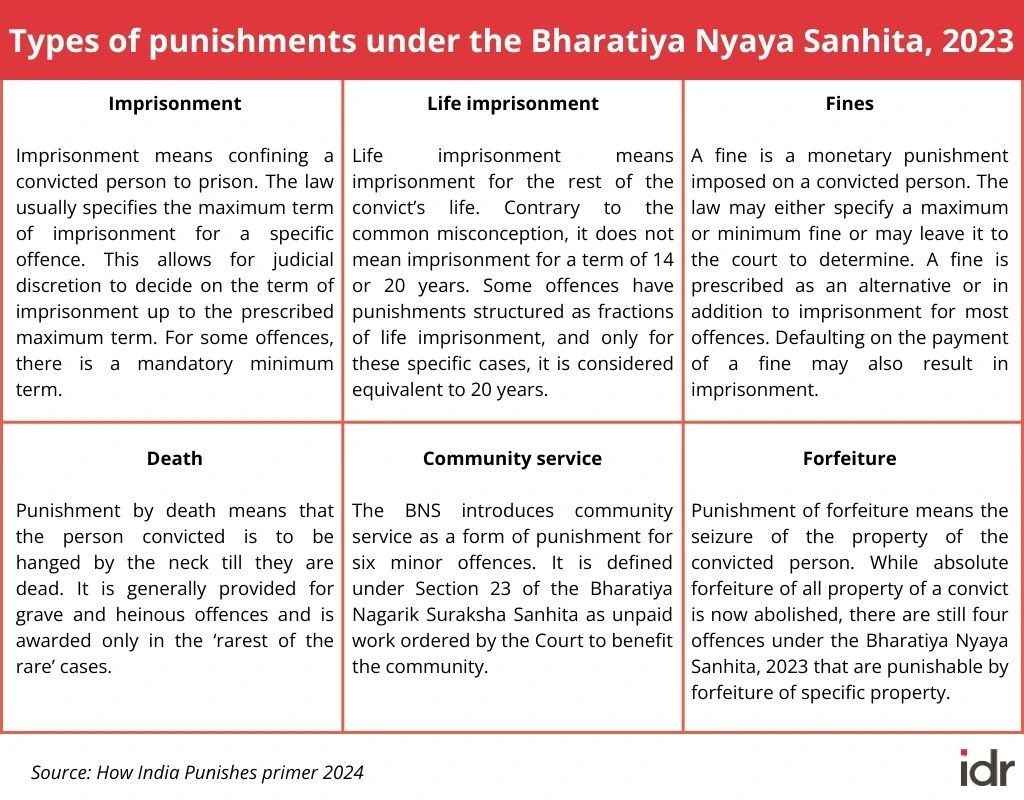

The past two years have seen some policy shifts aimed at addressing these issues and reassessing the role of criminal law in governance. The introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, Bharatiya Nagarika Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023, and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA), 2023, aimed to modernise and decolonise the criminal justice system by adopting citizen-centric procedures, introducing timelines for fast-tracking processes, integrating the use of forensics and technology, making the criminal justice system victim-oriented, and prioritising justice over punishment. Similarly, the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of Provisions) Act, 2023, sought to decriminalise and rationalise punishments for offences, with an intent to improve ease of business in India.

Even though these reforms are a positive step towards acknowledging the problems within the existing system, they have largely failed to disrupt the status quo. The BNS, for example, continues to prescribe punishments arbitrarily. Offences such as defamation, sedition, and crimes against religion remain on the books, perpetuating an outdated framework. One notable addition is the introduction of community service as a form of punishment, but this provision applies to only six offences, limiting its impact.

In essence, India’s legislative landscape continues to be replete with criminal provisions and punishments that do not fit the crime, and governance that is over-reliant on criminalisation.

Reimagining crime and punishment in India

Criminal law should be limited to addressing actions that cause harm to individuals, public order, security, or property, or have a direct and plausible connection to such harm. Countries such as Croatia and Slovenia, for instance, have penal codes that explicitly limit criminal sanctions to acts that threaten or violate personal liberties and human rights.

For issues beyond this, which still require regulation, the state must envision alternatives to punishment or at least alternative forms of punishment. For example, in Australia, there are various alternatives, such as intensive correction orders, drug and alcohol treatment orders, and non-conviction orders—which provide enough discretion for the court to make the punishment fit the crime.

Reimagining criminal law, however, would require addressing some crucial questions: What is the true purpose of criminal law for modern India? What objectives are served by punishing individuals? Are there more effective alternatives to achieve these objectives? And ultimately, are we solving any problems by criminalising conduct, or merely creating new ones?

A concrete policy on criminal law-making—one that includes criteria for criminalisation, pre-legislative impact assessments, and rules for determining the forms and quantum of punishment—can help eliminate unnecessary and arbitrary criminalisation. Similarly, a framework for prescribing punishments would ensure coherence and consistency in the use of jail terms and fines. In the absence of clearly laid-out sentencing guidelines for judges, such a framework would make a significant difference in ensuring that punishments fit the crime.

—

Footnotes:

- We analysed 25 post-Independence laws that have been categorised as laws relating to criminal justice by the Law Commission of India in its 248th report to identify these values

- Courts have struck down provisions criminalising begging, homosexuality, attempt to suicide, and adultery. In these cases, the courts have laid down a general guiding principle that discourages criminalisation when it violates fundamental rights or personal autonomy, or is discriminatory.

This article was updated on 12 November 2024. The usage of ‘Treasure Trove Act, 1954’ was corrected to ‘Indian Treasure Trove Act, 1878’.

—

Know more

- Read this primer on Reimagining crime and punishment: Towards better law making.

- Read this article to learn about what feminist approaches to justice look like.

- Watch this discussion on India’s new criminal laws.