I am not your data, nor am I your vote bank,

I am not your project, or any exotic museum object.

This poem by Adivasi scholar and activist Dr Abhay Xaxa is a poignant critique of how marginalised communities are reduced to data points, with our histories framed only through loss, erasure, and deprivation.

For nomadic and denotified tribe (NT-DNT) communities, resistance to such erasure means resisting state-imposed classifications that criminalise and invisibilise them. Articulating our own narratives requires moving beyond rigid, restrictive legal and bureaucratic labels such as ‘habitual offender’ that are a cause of discrimination, and asserting our identities on our own terms. This also necessitates attempting to flip the otherising gaze and creating our own narratives through education, learning, and experiential knowledge.

NT-DNT communities make up 10 percent of the Indian population, with figures hovering around 150 million. And yet, according to a 2015 report on Maharashtra’s educational status, an alarming 75 percent of the children from NT-DNT communities residing in pal podas (huts and shacks) or Pardhi bedas (temporary settlements) have never attended school. Furthermore, the dropout rate among NT-DNT children is significantly higher than those belonging to other marginalised communities. The dropout rates increase as children progress from upper primary to higher grades, indicating a severe barrier to sustained educational attainment among these communities.

What are the issues, and what can be their solutions?

In 2009, India passed the Right to Education (RTE) Act, which mandates the state to guarantee basic education for all children. However, while education is a fundamental right, it does not exist in isolation; rather, it is deeply influenced by social, political, and economic factors.

The social sector should acknowledge and promote NT-DNT communities’ access to quality education and opportunities. Here’s how:

1. Promote community leadership and political representation

It is important to hone leadership within nomadic communities so that we can represent ourselves. Particularly, it’s crucial for nonprofits, academia, and civil society organisations to reach out to micro-communities—Vadar, Kanjarbhat, and Ramoshi in Maharashtra, to name a few—via outreach, advocacy, and intervention. The idea is not to work onsome community but to work with them, and to make sustained efforts to push a generation of that community into the fold of higher education, eventually bringing them into the decision-making process.

For example, at Eklavya India Foundation, we’ve been able to create a new generation of leadership within first-generation university students from historically marginalised communities by encouraging dialogue—the ground leadership continuously informs the organisation’s work and practice. Our students go on to become mentors themselves. By sharing their background and context, they are able to facilitate holistic capacity building and development. These same students often take on leadership roles within the organisation, creating a cyclical model of giving back to society. Many of the Eklavya students have also become role models for their community.

When students from under-represented NT-DNT groups study in premier educational institutes, they often carry a responsibility with them to uplift their communities. These students strengthen the campus with their knowledge and experience, and, in turn, inspire a new generation to continue their education.

2. Research and rebuild the narrative

Currently, media narratives on NT-DNT communities are often coloured by the criminal prejudice against them. In academic research, due to the absence of scholars from the community, researchers usually carry unidimensional perspectives. To remedy this, we need:

To classify correctly: In order to get a clear picture of the NT-DNT status, it is imperative to collect official statistics via a population caste census of these groups. This is a prerequisite to policymaking and implementing measures related to the integration of the communities into mainstream education and work opportunities. India has a complex caste and sub-caste structure, and the lack of comprehensive socio-anthropological studies makes it challenging for government officials to accurately identify and classify the communities. For instance, the Banjara community is categorised as a Scheduled Tribe (ST) in Andhra Pradesh, as an Other Backward Class (OBC) in Rajasthan, and as a Denotified Tribe (DNT) in Maharashtra. Similarly, the Kaikadi community in Maharashtra is classified as a Scheduled Caste (SC) in some areas, such as the Vidarbha region, while being placed under the Nomadic Tribe (NT) category elsewhere.

These inconsistencies create huge barriers in uniform access to central and state government welfare schemes. To address this, a standardised classification framework is needed so that confusion can be eliminated and equitable entitlement to benefits (Nirman Recommendations, 2011) can be ensured. Furthermore, dedicated NT-DNT committees should be instituted at the government level, along with making budgetary provisions. This will ensure a distinct reservation policy for the communities, proportionate to their population within existing categories such as ST and SC. This distinction will help guarantee that socio-economic and developmental measures are implemented in a just and equitable way.

Additionally, this is where organisations working at the grassroots can help. These organisations understand the contexts of the communities, and can collect and share caste data. They are uniquely positioned to drive meaningful change by bridging the gap between marginalised groups and policymakers. Additionally, their on-ground knowledge allows them to systematically collect and analyse data and narratives, which is essential for exposing the specific challenges faced by subgroups.

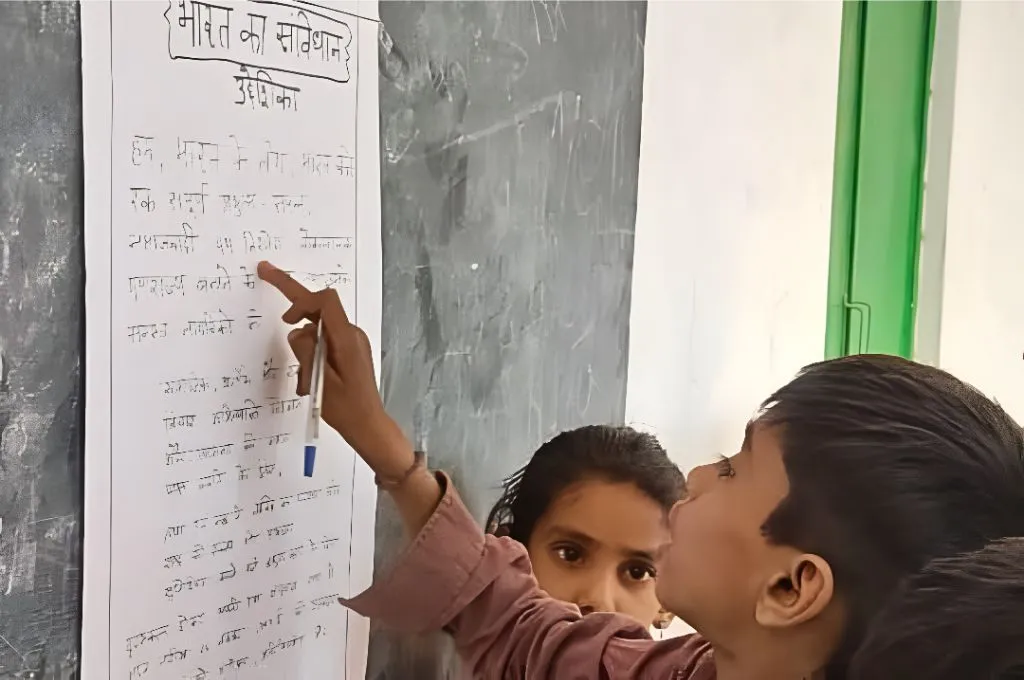

To redefine education by including lived experience: In India, the educational system has often reinforced social segregation and exacerbated economic disparities. Organisations that work with these communities need to model and advocate for an educational framework that acknowledges and integrates the cultural and practical realities of nomadic life. This is key because NT-DNT communities’ access to quality education in India has been largely overlooked in empirical research and policymaking.

3. Connect to rights, benefits, and entitlements

Various reports (such as Idate and Renke) make crucial policy recommendations, many of which are around the role of bureaucracy. The district administration must urgently issue caste, birth, and death certificates to NT-DNTs. The absence of such documentation keeps students out of school because they cannot avail scholarships and financial waivers, or access textbooks and uniforms provided by the government. In fact, in the absence of an authority or division to look after NT-DNT grievances, the community does not know who is responsible for their redressal. Thus, we should demand the creation of a separate body for NT-DNT affairs and grievances.

While bureaucracy is the main player in implementing policies and schemes, many nonprofits also work closely with governance structures. Advocating with administration can go a long way in securing the right documentation for NT-DNT community members and ensure fair, equitable, and just citizenship guaranteed by the Constitution to every member of this country.

4. Recognise historical marginalisation in education

The exclusion of nomadic communities from education is a multifaceted issue rooted in historical stigmatisation, systemic discrimination, and policy failures. While the denotification of these tribes officially occurred decades ago, the lived realities of many individuals from these communities continue to reflect exclusion and marginalisation.

Beyond policy-level interventions, inclusion in educational settings for NT-DNT communities requires comprehensive support systems. These include pre- and post-matric scholarships, hostels for boys and girls, study circles, and Ashram schools in remote areas to cater specifically to local NT-DNT students. Residential facilities are especially important, as students from nomadic communities need stable, long-term environments to access quality education. Additionally, exclusive NT-DNT training and academic research institutes should be formalised by the government. As of now, existing mechanisms also fall short. For example, while the National Overseas Scholarship has an NT-DNT quota, only six seats are offered to students from these communities.

However, addressing this exclusion requires not only targeted policy interventions but also a broader societal shift in attitudes towards these communities and implementation of existing schemes, which is again where nonprofit organisations have a significant role to play.

5. Mobilise as a category and as an identity

NT-DNT communities are not enumerated separately in the Census of India, nor are they seen as a special category in need of protection. Because of this, most of the reservation given to NTs and DNTs are carved out of SC, ST, and OBC reservations. In some regions, the lack of documentation and records even puts NT-DNT communities in general caste categories.

There must be specific provisions addressing the welfare and development of NT-DNTs. Take the Eklavya Model Residential Schools (EMRS) for Adivasi schoolchildren as an example. The schools offer opportunities into higher and professional educational courses. Yet they are inaccessible to NT-DNTs, because the classification of nomadic groups into castes or tribes is often inconsistent and arbitrary across states.

Without adequate representation in government policy, politics, business, knowledge production, media, judiciary, bureaucracy, and law enforcement, the systemic barriers to our education will persist, reinforcing exclusion and limiting opportunities for social mobility. Bridging educational gaps for NT-DNT communities can enhance our quality of life, while also driving us towards social and economic progress.

Finally, when words fail, artists come to the rescue.

“Which country? Which rights?

Give them to me too,

Come on, let it ride to my Pardhi home.

Oh democracy. Democracy is blind

to nomadic and denotified communities’ addresses,

However, fuelled by faith in democracy,

I hope that it will soon find the addresses of these communities.”

—