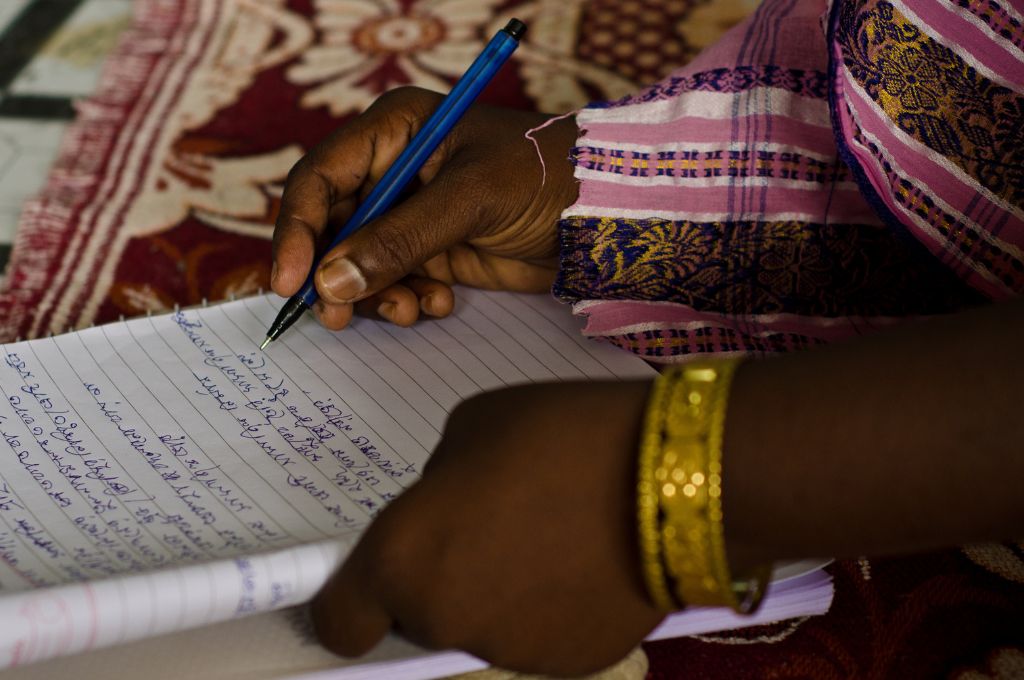

Fieldworkers form the backbone of India’s nonprofit sector. According to a 2014 report by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), civil society organisations (CSOs) account for more than 27 lakh jobs and 34 lakh full-time volunteers, a majority of whom are engaged as fieldworkers across the country.

These fieldworkers are exposed to a wide range of environments—from highly dense urban areas to virtually uninhabited rural areas. They often handle a large number of community relationships, manage delicate government associations, transfer on-the-ground insights to their own teams and external stakeholders, and act as first responders for the communities.

While the importance of their role cannot be overstated, the challenges of fieldworkers are often poorly understood, and documented even less, especially from their perspective. In this article, we look at what can be done to unlock the true effectiveness and potential of fieldworkers in order to further the impact of their work while enabling greater work–life balance.

We conducted a study focused on the productivity of fieldworkers by reaching out to 40 fieldworkers to better understand their struggles. The study also included one-on-one interviews with seven of these fieldworkers to discuss their perspectives and possible solutions in greater detail. We spoke to fieldworkers across a few different sectors such as education, livelihoods, and rural development from states such as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha. Forty-three percent of these fieldworkers belonged to national-level organisations (operating in more than three states) and 57 percent were from regional organisations. At least 40 percent of all frontline professionals interviewed belonged to organisations with a strength of more than 100 people. The fieldworkers we surveyed often had a large number of workers to manage, with 33 percent of them managing more than 20 people.

The findings from our study as well as conversations with heads of organisations are shared in this article with the aim of better supporting and improving the lived realities of fieldworkers in the development sector.

Key challenges

Our study revealed six key challenges, which if addressed can significantly enhance the capacities of fieldworkers while increasing the impact of their work.

1. There is a high reporting burden

The growing need for data-led reporting across the ecosystem has led to the prevalence of myriad reports–for funders, on monitoring and evaluation, on project implementation, communication and more, resulting in a notable increase in the administrative burden on fieldworkers. Anand, who works in Rajasthan’s Alwar district on livelihoods, animal husbandry, education, and rights, told us, “I have to manage field data on a daily basis within my organisation. There are 30–32 formats related to data that I have to fill every month. Because of this, I feel overburdened. If additional people were appointed to assist me, then my work would be much easier.” Approximately half (45 percent) of the fieldworkers surveyed mentioned that there are no uniform reporting formats, which leads to confusion and more effort. One fieldworker associated with a prominent nonprofit mentioned that they have no formats at all; each worker files reports in their own unique way. The workers we interviewed also said that the time spent on reporting significantly takes away from fieldwork, with 50 percent stating that report writing takes way longer than it should.

2. There are gaps in functional skills

Our study showed that a considerable amount of convergence is required on specific functional capacity-building needs. While there are organisations that invest in the capacity-building needs of their teams, it was found that fieldworkers across the board are seeking much more guidance in enhancing their functional skills. An overwhelming majority—75 percent—said they require assistance in improving their report writing skills. Approximately 68 percent mentioned that they need help with becoming more proficient at their work, and approximately 63 percent said they would benefit from more support in learning English. For instance, Gokul, who belongs to Bundelkhand in Madhya Pradesh and is engaged with the migrant workers sector, said, “My work with the local community happens in Hindi. But when I have to provide a report of my work to my manager, the findings have to be translated into English. I use Google Translate for this purpose, but many mistakes occur in this process, which is a big problem.”

3. Managers struggle to understand (and act) on ground realities

Sixty percent of the respondents said their managers do not grasp the challenges they face on the ground. Neha, who works in the space of women empowerment and livelihoods, said, “Our managers often struggle to understand the reality of the field. They don’t provide us with adequate support to manage everyday tasks. Even when we make suggestions that they agree with, nothing is done to act upon them.” In our interviews, we found that the hierarchical nature of the relationship between the fieldworkers and their managers is very pronounced. This often leads to a communication gap. Soni from Bihar said, “Most of our work is with the community and even after allocating time, it often takes much longer to complete tasks—the community regards our work as secondary, and an hour-long task can take as much as four hours. This time is often hard to justify to our managers.”

4. Working with local government stakeholders is time-consuming

Working with government stakeholders can be unpredictable. This uncertainty is embedded in most fieldworkers’ daily operations, and is often not considered in their work plans and accountability metrics. Fifty-eight percent of fieldworkers reported that working with local government officials takes up more time than expected. Setting up meetings with them is not easy, and it usually takes hours for these meetings to begin. The workers told us that they often reach their meetings only for them to be cancelled at the last minute. Rahul, who is from Rajgarh district in Madhya Pradesh and works in the education sector, said, “A lot of time is spent in setting up meetings with the officials and waiting for them to meet with us. Due to this, other work often gets held up.”

Workers also reported excessive coordination with government stakeholders, with one fieldworker stating that they have to manage more than 80 active WhatsApp groups on a daily basis as they work with different Anganwadi workers, supervisors, and child development programme officers.

While there is little that can be done to change the external ecosystem, acknowledging this occupational hazard and building in greater contingencies would be the first step towards finding a solution.

5. Building strong relationships with communities is difficult

As the development ecosystem focuses more and more on impact at scale, the depth of relationships with local communities is being affected. Amit Kumar, who belongs to Rajasthan’s Udaipur district and works on livelihoods, reported, “We are expected to cover many more villages and people compared to a few years ago. It can take months before we get to meet the same community member again. As a result, we are not able to build deep relationships with them.” However, at the same time, fieldworkers mentioned that the communities’ expectations from them are higher now—a result of the advent of technology and government initiatives due to which they have more information and resources than before. For fieldworkers, these expectations are becoming increasingly difficult to fulfil.

6. Fieldworkers face job insecurity and uncertain pay

While 35 percent of workers said that they do not receive fixed pay, 37 percent reported feeling low job security and a fear of losing their jobs in less than a year. Amit, who is from Badwani district in Madhya Pradesh and works on disability and gender issues, mentioned, “My monthly salary is INR 15,000. Every month I have to meet certain targets to receive my entire salary. These targets are typically too high for me to achieve, and so I usually get a salary of only approximately INR 12,000.” Multiple fieldworkers said that they were afraid of being let go owing to constantly changing organisational priorities. These workers are often part of single-income households with large families; hence, a loss of income would present a great risk to the entire family’s livelihood.

What can nonprofit organisations do to support their frontline workers?

1. Get a pulse on your frontline workers

Enable frontline workers to share their experiences without fear of judgement. Once you know more about the knowledge they possess as well as their strengths and weaknesses; the time and work management tools they deploy; and the status of their relationships with their peers, managers, and the community at large, you will be able to find solutions that address the source of their problems.

2. Categorise their challenges into three areas of action

The solutions you can consider lie in three distinct action areas:

- Capacity building and training for fieldworkers. Sessions on effective communications, computer-based skills, and management techniques are some examples of this.

- Developing processes and standardisation efforts to increase the effectiveness of fieldworkers. This could include creating formats and templates for reports and simplifying processes in everyday work.

- Creating safe spaces and bottom-up initiatives that enable workers from different locations to come together and share on-the-ground challenges and solutions both among themselves and with management. This can contribute to a culture where bottom-up decision-making is encouraged, channels of communication from the top leadership to the frontline teams are accessible, and spaces are created for field team members to share their experiences.

3. Devise solutions (and share them with us)

You can implement solutions in just one critical action area to begin with. But before you do so within your organisation, ask yourself the following questions:

1. Is this solution likely to enhance the well-being and impact created by our fieldworkers?

2. Can this solution be easily adopted by fieldworkers at large? Have fieldworkers and managers sufficiently weighed in and shared their ideas and concerns?

3. Will we be able to launch this solution relatively easily and soon, say, in the next one or two months?

4. Does this solution require additional funding? Do we have an existing funder who might be willing to provide philanthropic capital for these efforts?

We hope that, through these findings, you are able to identify potential areas of intervention and improve as well as build on the work that your fieldworkers are doing. We constantly hear from nonprofit partners about how indispensable their fieldworkers are, and many of you may have already faced and tackled the challenges mentioned in this article. If you have implemented effective field-level solutions at your organisation, and would like to bring these solutions to peers and other stakeholders who might benefit from your experiences, write to us at writetous@idronline.org or hindi@idronline.org.

—

Know more

- Understand how nonprofits can unlock the potential of their fieldworkers.

- Learn how to recognise and manage microstress.

Do more

- If you have implemented solutions to enhance the productivity and work-life balance of your frontline workers, and would like to bring these solutions to peers and other stakeholders who might benefit, then share them with us at writetous@idronline.org or hindi@idronline.org.