In recent years, Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) have come to be seen as the ‘gold standard’ of development research, monitoring, and evaluation across the majority world. This is because randomisation, when compared to other methods, is considered a less biased and more rigorous tool to examine cause–effect relationships between an intervention and its outcome.

The way RCTs work is fairly straightforward. A test (or treatment) group receives an intervention (for example, a new way of receiving payments by mobile phone or a smokeless cooking stove) while a control group does not. Members of each group are randomly selected to make both groups statistically identical and representative of the larger population. In theory, then, the only difference between the two is whether or not they receive the intervention. The outcomes can then be compared to evaluate the nature and extent of the intervention’s impact.

However, this approach often falls short of engaging the participants in the intervention as experts of their own experience. Because RCTs have roots in scientific experimentation, their design limits their agility to adapt the intervention to participants’ feedback. Moreover, their design is not flexible enough to respond to the wider social, political, and economic context that participants experience concurrently with the intervention. This poses problems in identifying and questioning the systems and structures that create equity challenges in the first place. More often than not, this results in evidence that presents only a partial understanding of the impact created and does not always advance equity.

As an alternative, tools such as feedback, surveys, focus groups, testimonials, diaries, or participant councils derive from a method called participatory action research. As the name suggests, it involves researchers and participants working together to identify problems and take action to solve them. Here, participants are seen as experts of their own lives. The incorporation of their experiences can help challenge inequality, while building more inclusive policies.

An extension of this approach is participatory evaluation, which gives programme participants, staff, and other stakeholders ownership in designing and managing the evaluation process itself. What sets this approach apart from more traditional approaches are the questions it asks:

- Why is the evaluation being done?

- How is the evaluation being done?

- Who is doing the evaluation?

- What is being evaluated?

- For whom is the evaluation being done?

Experimental methods like RCTs continue to be held in higher regard and considered essential to making programme or policy decisions.

As a result, the evaluation questions are likely to be more locally relevant and empowering for participants, and will be able to establish and explain causality. While funders, nonprofits, and governments are increasingly recognising the importance of participatory methods, experimental methods like RCTs continue to be held in higher regard and considered essential to making programme or policy decisions.

To build the case for why impact evaluations need to expand and integrate the use of participatory approaches with experimental methods, US-based social impact advisory Milway Plus, and Florida-based nonprofit Pace Centre for Girls recently conducted a study.

Their research aimed to understand whether participatory methods can help organisations measure outcomes better, as well as make them more equitable and inclusive. Between February and March 2021, they surveyed, interviewed, and conducted focus group discussions with 15 nonprofits that have embraced participatory measurement. In addition, the research team reviewed the evaluation literature and interviewed evaluation experts at other nonprofits, funders, and measurement intermediaries.

Their study found that a holistic approach—blending participatory methods with data from empirical studies—not only helped establish causal links between programmes and outcomes but also influenced organisations to be more inclusive. While the study focused primarily on US-based organisations, its findings are relevant for nonprofits in India when thinking about programme design and evaluation.

Who determines what impact matters most?

Several organisations that participated in the study were conducting multi-year research to explore how participant feedback connects to outcomes. Preliminary findings suggested causal links between the two. Nonprofits shared that participant feedback helped them learn more about what works, what doesn’t, and how different components of the programme intersect with each other to produce the desired outcomes—things that they would not have learnt through RCTs or other purely quantitative evaluations. They were then able to use these insights to strengthen their programmes.

Additionally, participatory evaluation allowed nonprofits to focus on things that a funder might not necessarily prioritise, but that matter to the communities. At the core of this approach is the question: Who determines what impact matters most?

Building rigorous evidence of impact also needs organisations to ask the right questions.

Bias is inherent in all measurement and data interpretation, but participatory methods are biased in favour of the people who must live with the impacts of a programme. For instance, Harlem Children’s Zone, a nonprofit working on improving education outcomes for children, highlighted the importance of being able to prove the value of an intervention to parents—something that falls outside the purview of an RCT.

Building rigorous evidence of impact also needs organisations to ask the right questions. Nonprofits that focused on participant-centred measures drew on community wisdom to get those questions right. Gift of the Givers, a disaster relief agency based in South Africa, gathers community members, funders, technical experts, and local authorities for face-to-face, real-time discussions on what’s working and what needs to change. Everyone has an equal chance to argue for what the community needs, what budgets are required, what local traditions will allow, and, ultimately, what needs to be done.

What are the wins for society?

Perhaps the most important argument in favour of participatory research is that it leads to advocacy wins that change systems and society. Think of Us, a service-delivery and advocacy group for foster youth, hires young people who have experienced foster care to be members of its research teams. When they reported direct testimonials from 78 foster youth of abusive experiences in group homes, the insights prompted child welfare leaders in several states to support policy changes.

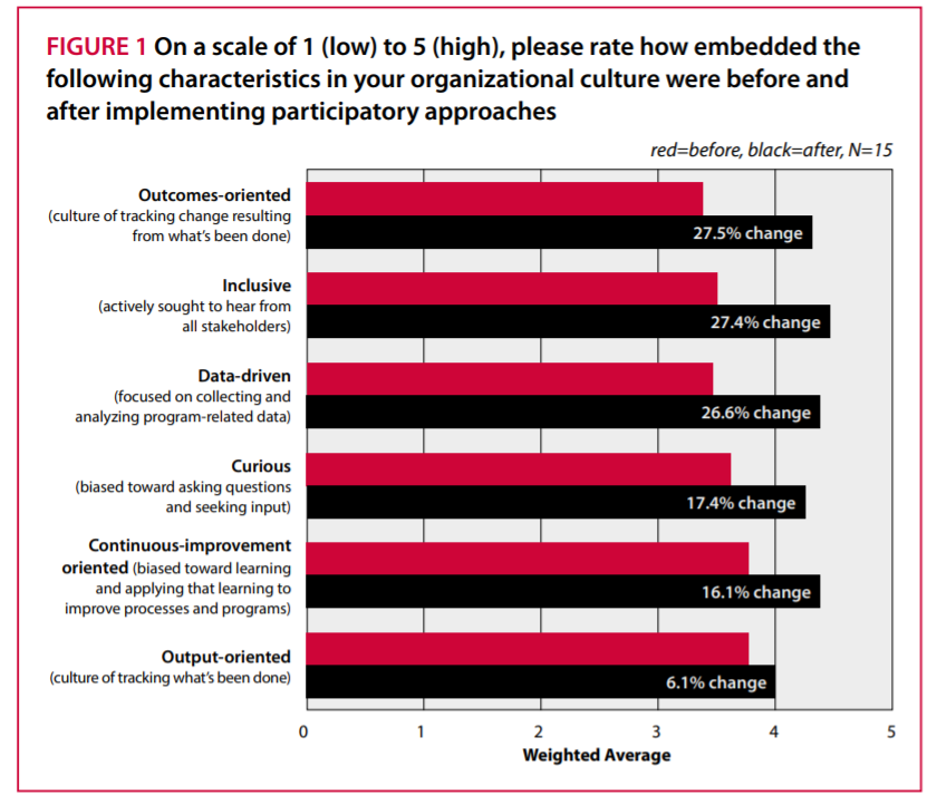

When focus-group participants ranked a series of characteristics of their nonprofits before and after the organisations implemented participatory methods, they noted their work became more outcome-focused (27.5 percent higher on average), more inclusive (27.4 percent higher), and more data-driven (26.5 percent higher). More than 70 percent of the organisations studied reported that participatory methods (most often surveys, focus groups, storytelling, and town halls) helped them define relevant outcomes, whereas experimental methods often framed an outcome so narrowly that the findings lost relevance. A core difference between the design of RCTs and participatory approaches is at the heart of the equity argument.

Embedding equity in organisations

Nonprofits that focused on participatory evaluation also noted positive knock-on effects in other areas of their work. They found themselves building more equitable organisations by way of using more inclusive practices in hiring, service delivery, talent development, technology, and communications.

The shift in who is perceived as an ‘expert’ shaped a number of organisational decisions. For instance, 60 percent of the respondents said the use of participatory approaches in evaluation led them to hire differently. Specifically, this meant prioritising candidates with lived experience of the issues their programmes aimed to solve, who were good listeners, respected the community, and were comfortable with participatory tools.

For Pace Centre for Girls, this approach brought about deeper engagement with the programme and higher motivation among staff. In turn, this resulted in team-member turnover declining by nearly two-thirds within five years, and productivity and engagement increasing by more than a quarter. Not only did organisations hire differently, but they also created roles for participants on their teams so they could build skills and become eligible for permanent positions.

Further, all the organisations also reported increasing communications with programme participants, often by SMS or text. More than 60 percent of the survey respondents said their tech know-how and cross-sector relationships had grown through participatory practices.

Lastly, the organisations in the study found that blending experimental and participatory approaches generated insights on an ongoing basis and made them more adaptable. In 2020, the resilience and adaptability of nonprofits across the world was tested by the COVID-19 pandemic, among other health and economic crises. Organisations that had previously integrated participatory evaluation into their work found it easier to shift to new and virtual ways of listening to and working with communities to respond to the challenges they were facing.

Next steps for funders, evaluators, and nonprofits

The road to making evidence more equitable and participatory is a long one, and not without its set of challenges. But as funders, evaluators, and nonprofits embark on this journey, here are five questions they must keep in mind:

- Do we have a process that gives voice to the people most affected by our interventions and allows them to shape and influence how we evaluate impact?

- Are we disaggregating the data we gather by gender, caste, age, and any other relevant criteria to understand the disparate experiences of groups of participants within the overall results?

- Are we approaching our evidence building through an equity and inclusion lens by identifying and testing questions through appropriate focus groups or panels of participants?

- Are we calibrating outcomes to ensure they are equitable and not determined or predicted by other socio-economic factors (for example, gender, disability, or caste)?

- Are we using the data to inform programmes and strategies that are themselves in the service of equity?