“I know the CEO of a company, and yet could not get any CSR funds!”

“My proposal has been with the company for over four months, and still hasn’t been finalised!”

“I feel like I am expected to be project manager, accountant, and lawyer, all rolled into one!”

These are just some of the many exasperated comments we have heard from nonprofits, when sharing their experiences on partnerships with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) teams. CSR in India has often been criticised for its bureaucratic processes, delays, inability to bring risk capital, and a lack of understanding of the workings of the social sector. CSR decisions, to many, seem arbitrary and ad hoc. What is it about CSR decision making that makes it so drawn-out, slow and risk-averse? Who actually makes these decisions? And what are they based on?

This article tries to decode some of the nuances associated with internal CSR decision making processes at companies. The hope is that it helps nonprofits and other stakeholders develop an appreciation of corporate realities, just like companies are developing an understanding of the social sector, and in so doing, helps close the gap between these two parties.

The holy trinity of CSR decision making in a company

The initial years following the passage of the CSR regulation (Section 135, Companies Act 2013) were marked by a number of teething issues. Companies struggled to create meaningful internal structures that were capable of deploying funds strategically. CSR decisions were routed through department heads in human resources, marketing, corporate communications, or other teams. However, this trend seems to be changing now. Data on BSE 100 companies from 2018-19 shows that of the 76 companies that published this data, 40 companies had at least one dedicated CSR personnel (many had departments); another 17 had a CSR foundation, implying that 79 percent (60 out of 76) of companies had created or augmented in-house capacities to understand and respond to the needs of the social sector.

While having a dedicated team is definitely a positive indicator, it does not by itself ensure optimal decisions as CSR decision making is a more complex process that involves many other people besides the CSR team. In most companies, major CSR decisions are driven by a trifecta of the CSR committee, the CSR department, and the support functions.

The board and the CSR committee

Under Section 135 of the Companies Act, a company has to involve its board and senior management (including the CEO and CFO in most cases) via the CSR committee, in the decision making process. These individuals are and should be involved in strategic decisions—the CSR approach, expenditures, partners, risk management—and not in day-to-day operations. Corporate leadership’s oversight can bring in many advantages in terms of ambition, rigour, innovation, and diligence. The drawback however can sometimes be the lack of exposure that many senior leaders may have to the social sector and how things operate at the grassroots.

The CSR head

The CSR head is the most important person for CSR in the internal corporate set up. In most large companies, this person typically is a veteran, with many years of experience in both social and corporate sectors. They hold the accountability and responsibility for overall CSR strategy, execution, and compliance. However, one would be mistaken to think that they are the sole decision maker. In fact, this individual is always in the hot seat, with the unenviable task of brokering relationships and building consensus between critical actors: upstream with the board and senior management, laterally with other business heads and external implementation partners, and downstream with their own team. All of these come with different perspectives, motivations, and varying levels of understanding of each other’s dynamics. A CSR head’s competence, capability, charisma, and fortitude thus play a pivotal role in a company’s CSR journey.

Many companies are trying to sensitise their internal support teams on the workings of the social sector.

In smaller companies, the hat of CSR head can be donned by a senior leader in another corporate function, commonly the company secretary, HR, or corporate communication head. The role may even fall directly under the CEO. Even in these cases, the decision making seldom rests with just that one person.

The support functions

What many actors in the social sector fail to realise is the role played by the seemingly unrelated functions of finance and accounting, legal, and procurement, in CSR decisions. While invisible and indirect, these departments often act as gatekeepers, deciding what is permissible and what is not. In many cases, these stakeholders would have probably never engaged with nonprofits or the social sector as their corporate roles would not have needed them to. They therefore prefer to opt for the letter, rather than the spirit of the law, focusing on compliance and risk avoidance and trying to transpose corporate process, templates, and contracts to social programmes. They do this not because of mal-intent, but simply because they do not know better. Many companies are trying to sensitise their internal support teams on the workings of the social sector. Some that have separate corporate foundations have set up distinct support teams consisting of accountants, lawyers, and finance managers, with experience of the social sector.

When it comes to companies with a large manufacturing footprint, a further layer of decision making is involved since most factories or plants also have a local CSR structure, made up of plant leaders and support services at the plant level.

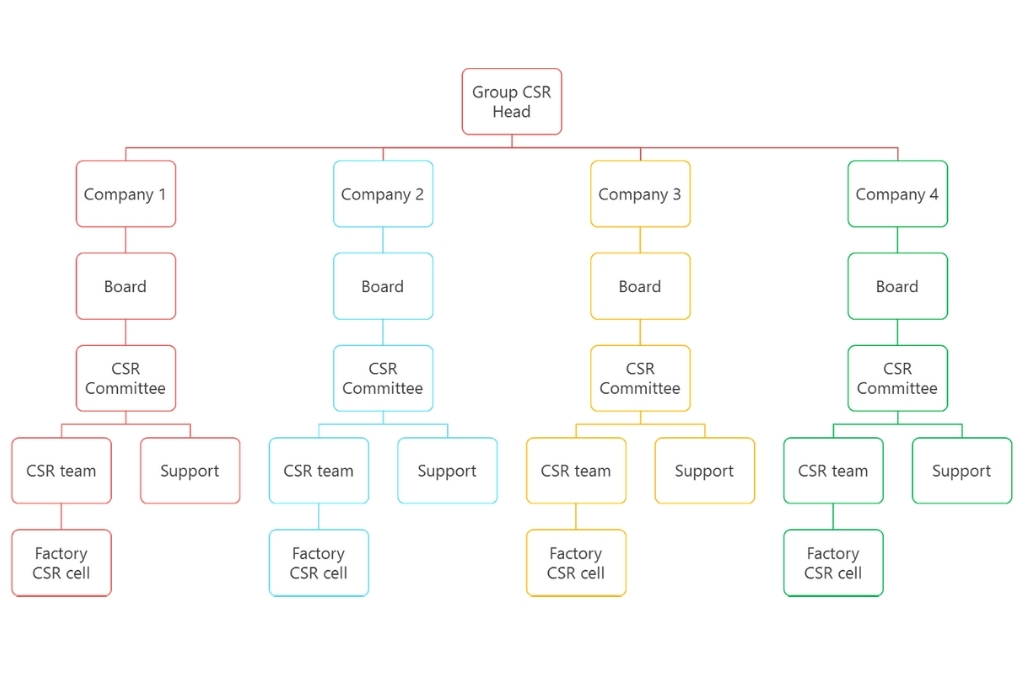

And in the case of group companies or conglomerates, the above structure is multiplied many times, as shown below. One of the CSR heads I know quipped that his quarterly board meetings typically had more than 20 people, where each decision was akin to defending a doctoral thesis!

Let us now consider an example to see how different internal stakeholders respond to a situation. In my role as a CSR consultant, I was once working with an infrastructure company. The CSR head was keen to partner with a social enterprise (registered as a private limited) providing an edtech solution for one of its education projects. We had done a fairly comprehensive scoping exercise to identify the right partner, and had zeroed in on this social enterprise due to the quality and comprehensiveness of its solution.

The conversation during the CSR committee meeting went as below:

CSR head: We have selected this social enterprise since it has the most fitting solution to solve this particular educational issue by using a software that responded to every child’s specific learning needs and performance. It has evidence to show that learning outcomes among its students are three times as high as those not participating in their programme.

CSR committee member: Why should our CSR funds help some startup grow? Can we not find a nonprofit with a similar solution?

Company secretary: Is working with a for-profit compliant with Section 135? How will we ‘report’ it in our MCA 21 filing?

Legal team: If this is a vendor contract, should we add performance guarantee, similar to other vendors? Does the enterprise have insurance to cover for potential damages or losses in the operation of the programme?

Procurement team: If this is a for-profit, it will charge a GST, making it more expensive than working with a nonprofit offering a similar service. Why should CSR funds go towards paying taxes and levies instead of to end beneficiaries?

Finance team: The overheads look high. Is this because it is a for-profit? Have you done a cost comparison and benchmarking of salaries for this enterprise?

CSR as a strategy is expected to work within the overlap of business objectives, government priorities, and local community needs.

All these questions were justified from the respective teams’ lenses: they demonstrated fidelity to the role of that team within the company, and they analysed different aspects of the situation. But in silos, they were missing the big picture that this was the solution that was most likely to optimise outcomes. It took the CSR head multiple rounds of conversations over two to three months to assuage the concerns and build consensus. In this light, it’s easy to see why a CSR head may just cave in or why this enterprise may have to wait for almost five months to receive the final go-ahead (which is what happened in this case).

While the decision making process itself is quite democratic within the company, when people with different mandates and competencies are looking at the issue, it’s important to speak their language and show them the value of the approach and above all, sensitise and educate them.

The reason why CSR decision making process has evolved into a complicated process can be explained by a couple of factors. Unlike individual philanthropy, which can be mainly directed by an individual’s passion or approach, CSR as a strategy is expected to work within the overlap of business objectives, government priorities, and local community needs. It also has to address the expectations of, and be accountable to stakeholders within these three groups. Any imbalance between these three results in a skewed decision. For example, many companies feel compelled to change their focus areas to mimic the next new priority put out by the government—Swachh Bharat, Skill India, PM CARES, to name a few—since maintaining good government relationships is key to business operations.

For some companies, CSR as a function is still young and capabilities and systems around it are evolving, including the ability to ringfence its spending from ad-hoc requests. Additionally, making CSR a regulatory requirement has resulted in increased scrutiny and diligence. And lastly, CSR also reflects the dynamic nature of the development sector itself in India, where many building blocks in terms of common taxonomy, talent, management practices, and impact measurement are constantly evolving. In order to ensure that CSR decisions truly contribute to achieving social impact, companies need to adopt a results-based management approach, and be open to learning and growing. And the social sector ecosystem needs to have the patience and perseverance to educate and empower them to make informed decisions.

—