Numbers related to India’s education sector are mind-boggling, to say the least. With more than 1.5 million schools (1.1 million of them run by the government) and more than 250 million students enrolled in them, the country’s K-12 school system is one of the largest in the world.

India’s education market, currently valued at USD 100 billion , is expected to nearly double to USD 180 billion by 2020, fueled by a growth of 30 percent CAGR in the online and digital learning market over the same period.

There is a significant mismatch between education spending trends and learning outcomes.

In terms of government spending, the Union Budget has pegged an outlay of INR 79,685.95 crore for the education sector for 2017-18. Of this, nearly 60 percent (INR 46,356.25 crore) is for the school sector and the rest for higher education.

On the corporate front too, education received the highest amount of CSR funding among all social development activities in 2015-16: 920 National Stock Exchange-listed companies together spent INR 2,042 crore on education, up 30 percent from INR 1,570 crore in FY15.

Add PE money, strategic investments, and grants provided by various foundations–and the amount of money in circulation in the education space is quite substantial.

Despite these large investments by both the government and private sector, quality remains unsatisfactory. There is a significant mismatch between education spending trends and learning outcomes that calls for a serious introspection of our education policy and practice.

Where did the money go?

Private capital

The Indian education landscape can broadly be classified into pre-school, K-12, higher education, tutoring and test prep, vocational training, and multimedia & ICT.

According to VCCEdge, of the 289 deals worth USD 919 million registered since 2012, more than 56 percent has gone into test prep (USD 217.57 million) and e-learning portals (USD 301.29 million).

Within the test prep segment, learning app maker BYJU’s alone received USD 150 million in 2016-17. This was approximately 50 percent of the overall VC money received by all ed-tech companies till December that year and 22 percent of the total money received in the K-12 segment in the last seven years.

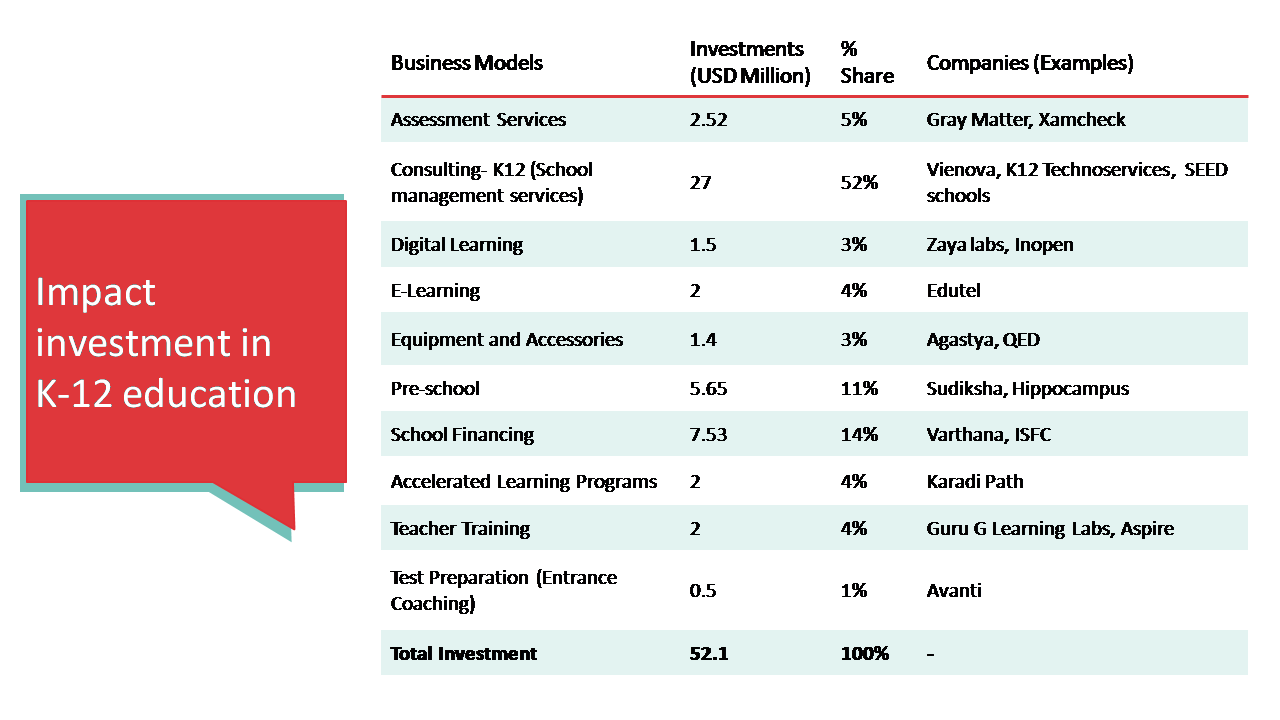

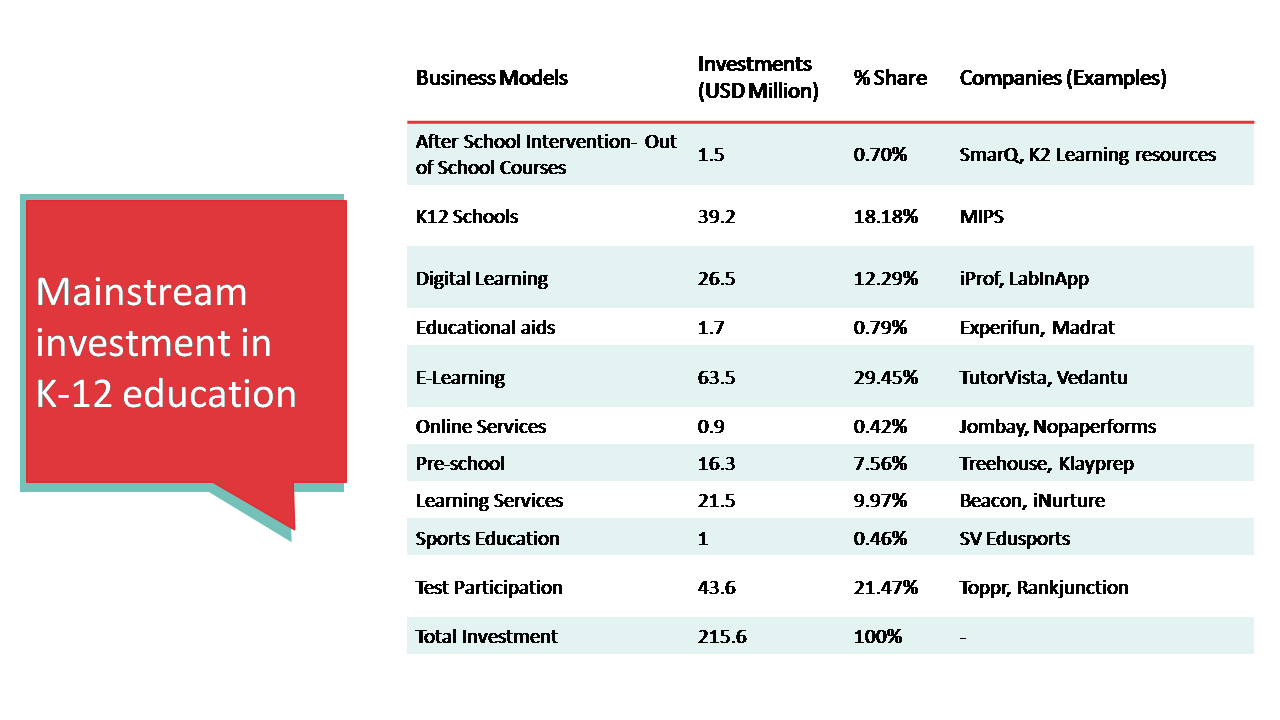

That’s not all. Even within the K-12 segment, approximately 50 percent of the investments have gone to test prep and e-learning.

The table below highlights the distribution of the major equity deals in this segment in the last six years.

This disproportionate investment in certain segments has resulted in some imbalances in the sector:

- New entrepreneurs generally see this as a signal that the segment is lucrative and develop sub-par business models that are not aligned with the objective of improving learning outcomes.

- Public and private investment in earlier stage education (pre-school and K-12) is proving to be insufficient resulting in a large gap in the skills taught and those required by industry. This disparity between the knowledge acquired in school and those evaluated through standardised tests has also resulted in a burgeoning test-prep industry.

This, in turn, has diverted funds from the other segments into this lucrative category, setting in motion another cycle of skewed investment patterns.

Government spending

The anomalies in investment are reflected in government allocations as well, but of a different kind. As against an allocation of INR 5 crore last year, the school assessment programme has been allocated a paltry INR 67 lakh in the 2017-18 budget. Conducting learning assessment in a school system comprising 250 million students in more than 1.1 million schools with this amount is a tough ask, especially when all the players acknowledge that learning outcomes are critical.

On the other hand, the mid-day meal programme has been allocated INR 10,000 crore, up by INR 300 crore from the last budget. This meagre increase is unlikely to create a difference in the functioning of the scheme. However had this INR 300 crore been allocated to the Digital India E-learning initiative for higher education, which has been allocated INR 497 crore, or for the Department of School Education and Literacy (which has a meagre INR 14 lakh budget), both programmes would have benefited greatly.

Despite all these efforts, why haven’t we got it right?

Such skewed investment patterns point to some underlying problems in the country’s education sector and the inadequate response to them from various stakeholders, including government, corporates, and social enterprises.

Are we solving the wrong problem?

The government went in with the assumption that all teachers were good at teaching and would enhance learning outcomes, regardless of the context they taught in. This assumption allowed them to limit their role to providing access to schools for all children (through RTE) without paying any attention to the existing pedagogical system. That assumption has fallen flat.

Although ‘learning outcomes’ has become a talking point for policy makers, the government has chosen to not act on it even after admitting the flaw in their theory. The meagre budgetary allocations to school assessments and digital literacy are reflective of the government’s lack of focus on educational outcomes.

Further, a break-up of government spending shows that only 0.8 percent goes towards capital expenditure, while 80 percent goes towards teachers’ salaries, leaving little to be spent on infrastructure creation, which eventually translates into ineffective infrastructure and poor quality of education.

Technology isn’t the only answer

Several new-age entrepreneurs in the education sector believed that technology alone would improve the quality of education. Private players, entrepreneurs and tech believers assumed that well-designed products focussed only on enhancing the learning outcomes of students could replace teachers in the classroom and solve the problem of poor teacher quality.

This hypothesis led to the rise of business models and products with an inadequate focus on classroom execution and facilitation, leading to the failure of many good ideas that could have been successful if only the entrepreneurs had been careful about this assumption.

Over-regulation

The highly-regulated environment in the education space is a barrier to attracting quality entrepreneurial talent to K-12 education as compared to the higher education segment. The rise of innovative solutions in test prep and digital education can, to an extent, be attributed to this gap.

A blinkered view

There is little comprehension of the fact that the education sector’s challenges cannot be solved by attacking individual problems: it needs a concerted effort where problems are addressed simultaneously. Thus, teacher absenteeism must be tackled along with the problem of poor quality of teacher training. The problem of test prep must be solved along with the provision of good digital literacy to students in schools, especially in rural and semi-urban areas.

The consequences of not following a multi-pronged approach can be detrimental to the sector, as we realise the distorted impact of such moves only after a few academic cycles.

This is because learning outcomes are dependent on the exam cycle of schools and colleges. Any business model being experimented within the K-12 segment therefore takes at least two academic cycles to get validated in terms of its efficacy in creating impact.

An acceptance of this fact might help the entrepreneurs and investors become more patient and stick to fundamentally better solutions than just looking for easier exits.

What can the sector do differently?

The education system cannot be transformed by working in silos. Only when we take a holistic perspective can we talk about how impact investment is helping create the desired change in the sector.

Investors, foundations, governments, educationists, activists, entrepreneurs and other stakeholders are investing considerable efforts into the sector. But we need more. Here are a few things to consider:

- The incentives for all stakeholders–parents, teachers, students, principals, and school owners–should be understood with the goal of aligning them as far as possible to ensure improvement in learning outcomes. There is a great deal of literature available on the importance of incentive alignment and contract design, and it is time we translated these learnings into practice.

- Impact measurement metrics should be clearly defined and integrity of the data collected from the field should be validated. Pockets of excellence and average numbers on certain chosen parameters are not truly representative of the state of education in India.

- Weak business models that do not have well-defined impact or where the costs are too high compared to the impact generated should be allowed to perish. It is important for the market to let bad business models fail.

- Despite being the second largest education system in the world, there is a dearth of quality faculty at scale. There is a huge need for both quality pre-service and in-service training for teachers.

- Entrepreneurs should recognise that teachers are pivotal to success and must include them while designing the product or service. If there is no value proposition for them in using the product, then product adoption is going to be low and ineffective.

- Corporates should go beyond supporting tuitions, providing books, or building school infrastructure with their CSR funds, says Prachi Jain Windlass, director at the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation. “Firms could look to support processes organisations and initiaitves that have clear learning outcome targets, which are also easily measurable,” she says.

When we ask the right questions, identify the issues that really matter, and find and implement the solutions that address these issues, our children might learn better–and the numbers might begin to add up.

Research for this article was partly taken from ‘Impact Investing in K-12 Education in India‘ by Sudhanshu Malani (Investment Associate), Villgro Innovations Foundation.