Impact investing enterprises, a growing number of companies created to further a social or environmental purpose, have the potential to be a transformative force in confronting the major societal challenges faced by India.

Since 2010, impact investing’s support has expanded from microfinance to other sectors—such as agriculture, healthcare, and education—and annual investments have grown from USD 323 million to USD 2.7 billion. However, not all the trends point in the right direction, particularly from the perspective of investment recipients. To date, impact investors have heavily favoured ownership equity in emerging impact enterprises, over lending money for working or growth capital (also known as debt financing). Debt remains particularly challenging for young, growing impact enterprises to secure, in large part because of the perceived risk and lack of creditworthiness. Yet, without an adequate supply of borrowed money, expansion and working capital needs go unmet, leaving impact enterprises unable to reach their full potential.

To better understand these challenges, the India Impact Investors Council (IIC) and The Bridgespan Group have published a report which analyses the balance sheets of 422 leading impact enterprises and gauges their creditworthiness, identifies the barriers to debt financing, and proposes solutions for making debt more accessible.

Related article: IDR Explains | Impact investing

Barriers to debt financing

Cautious investors are only one component of this complex story. Our research and interviews with more than two dozen impact investors and impact enterprise leaders led us to conclude that all the lead actors in India’s debt ecosystem play a role—often inadvertently—in limiting access to credit. We summarise these obstacles below.

- Impact enterprises struggle to find and secure loans. As the CEO of one impact startup told us, they prefer debt to handing over a share of ownership for cash. Yet, the latter is often the only option for impact enterprises because they typically lack the collateral required for standard, asset-backed lending. Furthermore, many impact enterprises have not matured enough to be able to implement strong management reporting systems that capture critical financial, employee, client, accounts, products, and performance data. Weak reporting systems lead to low-quality financial statements that make it difficult—if not impossible—for impact enterprises to obtain a good credit rating.

- Non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) lend when banks are reluctant to. Bank lending practices based on collateral are more suitable for conventional asset-heavy manufacturing enterprises than for asset-light impact enterprises. Many, if not most, impact enterprises have few (if any) balance sheet assets such as equipment and inventory, to offer as collateral. As a result, loan officers often consider small enterprises too risky to pursue. By contrast, NBFCs specialise in servicing enterprises that banks consider too risky. However, the interest rates they offer tend to be higher, because their operating costs are higher than that of banks. This, in turn, puts a strain on the cash flow of many young enterprises, making it difficult for them to accept loans.

- Lack of data inhibits credit evaluations. Lenders acknowledge the need for more and better data to assess the creditworthiness of potential clients. To address this problem, the Reserve Bank of India in 2016 approved a new class of NBFCs to act as account aggregators to consolidate and digitise information from individuals and companies, and make it usable by financial institutions. Also, emerging data and analytics platforms such as Crediwatch can provide independent third-party data on the performance of companies. While none of these approaches are fully proven yet, their performance before the COVID-19 pandemic washed over the economy, was encouraging.

- Government regulations affect domestic and offshore capital. In recent years, the Indian government has taken steps to improve financing options for small-to-medium enterprises, but regulations that slow and even stymie debt investment and impact enterprises remain. For example, impact investing is not recognised as a distinct asset class that would allow regulators to apply a different of standards to impact investors and enterprises. Non-performing loan regulations lack flexibility to allow banks to make loan modifications to accommodate fluctuations in an impact enterprise’s cash flow. Regulations also prevent CSR funds from going to impact enterprises. Finally, external commercial borrowing is highly regulated by the Reserve Bank of India and comes with restrictions and guidelines that limit its appeal.

Making debt more accessible

The mismatch between debt financing supply (too little) and demand (too much) continues to impede the ability of social enterprises in India to fulfil their potential. As we heard from the impact investors and bankers we interviewed, a number of solutions are at hand.

The sector would benefit from the standardised tools and platforms broadly available to banks and other financial institutions. | Picture courtesy: Pixabay

This approach addresses a common complaint of small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) owners in India: Businesses fail to achieve their growth potential because banks won’t extend loans without collateral. Cash-flow lending allows banks, NBFCs, and fintech firms to extend loans based on the present and projected cash flows of the enterprise. Compared to conventional business loans, cash-flow lending requires less paperwork and shorter approval times, in part because it does away with the appraisal of collateral.

Cash-flow lending allows banks, NBFCs, and fintech firms to extend loans based on the present and projected cash flows of the enterprise.

Market observers expect cash-flow lending to be a boon for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), startups, and impact enterprises that may not have hard assets for collateral. In June 2019, the Reserve Bank of India recommended that banks should opt for cash flow-based lending. And the country’s largest lender, State Bank of India, announced early in 2020 that it planned to transition from asset-based lending to cash-flow lending. Whilst not aimed specifically at impact enterprises, cash-flow lending no doubt will benefit them.

These address the real and perceived risks that can keep commercial banks, NBFCs, and impact investors from providing debt financing to impact enterprises. For example, IndusInd Bank’s Impact Investing division actively seeks out guarantee deals, such as the USD 5 million in debt financing to Grameen Impact. The loan is backed by a guarantee from the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and supports Grameen Impact’s lending to local SMEs.

Many financial institutions participate in the guarantees by providing credit to otherwise underserved markets and organisations.

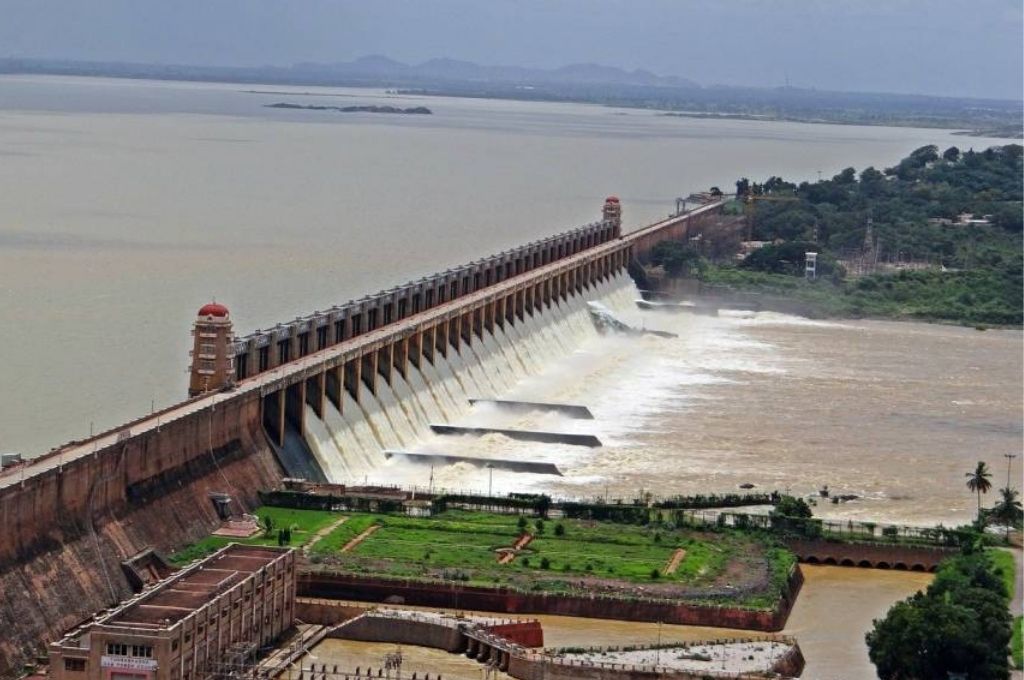

Rabo Foundation, the corporate foundation of Rabobank, a Netherlands-based cooperative bank that focuses on food and agriculture sectors globally, has demonstrated how credit guarantees can work in the Indian market for agriculture. Due to regulations on offshore funding in the agriculture sector, Rabo Foundation could not offer loans directly to Indian farm cooperatives. As a workaround, six years ago it introduced credit guarantees, starting with an organic cotton farmers’ cooperative. Many financial institutions now participate in the guarantees by providing credit to otherwise underserved markets and organisations. Subsequently, Rabo Foundation set up a warehouse receipt financing programme, an agtech support programme, and a climate smart agriculture financing programme for farmer organisations.

Related article: Five myths about impact bonds

AIFs have grown in popularity in recent years. It refers to any fund established in India that pools investment funds from institutional or high-net-worth investors, whether Indian or foreign, in accordance with a defined investment policy. The minimum investment from a limited partner is INR 1 crore. Today, more than 695 funds have registered with Securities and Exchange Board of India.

These methods go beyond traditional collateral-based lending to assess the creditworthiness of potential investees. All impact investors we interviewed have developed proprietary methodologies that vary greatly. At Caspian Debt, for example, each credit decision is approved by a centralised credit committee. Specialised teams conduct the due diligence through extensive desk and field research that includes facility and customer visits. The deal screening also includes a strict exclusion list for companies that do not meet environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards. By contrast, Vivriti Capital has developed a highly automated, quick-response credit underwriting platform called CredAvenue that links enterprises in need of debt financing with potential lenders.

Whilst proprietary platforms like these can validate new ways to pursue due diligence and credit underwriting, they remain the exclusive domain of their developers. The sector would benefit from the standardised tools and platforms broadly available to banks and other financial institutions.

Swasti Saraogi also contributed to this article.

—

Know more

- Read this article to know more about calculating the value of impact investing.

- Learn more about the promise of impact investing.

Do more

- Connect with the authors, Ramraj Pai, Sam Whittemore, Sudarshan Sampathkumar, and Swasti Saraogi, if you’d like to learn more about their work.