In community-driven development (CDD) programmes, communities are in charge of implementing and maintaining externally funded development projects. The underlying assumption of CDD projects is that communities are the best judges of how their lives and livelihoods can be improved.

These programmes have been implemented in low- and middle-income countries to fund the building or rehabilitation of schools, water supply and sanitation systems, health facilities, roads, and other public infrastructure.

While this sounds good in theory, this report by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) tells us that the impact of CDD programmes isn’t as effective as we thought.

Related article: Ordinary people, extraordinary power

The authors synthesised evidence from 25 impact evaluations, covering 23 programmes in 21 low- and middle-income countries (including Afghanistan, Benin, Bolivia, Indonesia, Nigeria, Peru, Senegal, Yemen, Zambia and others) to assess how CDD programmes have evolved over the years and what their impact has been. They also drew on qualitative research in order to examine the factors influencing success and failure.

Some of the report’s key findings

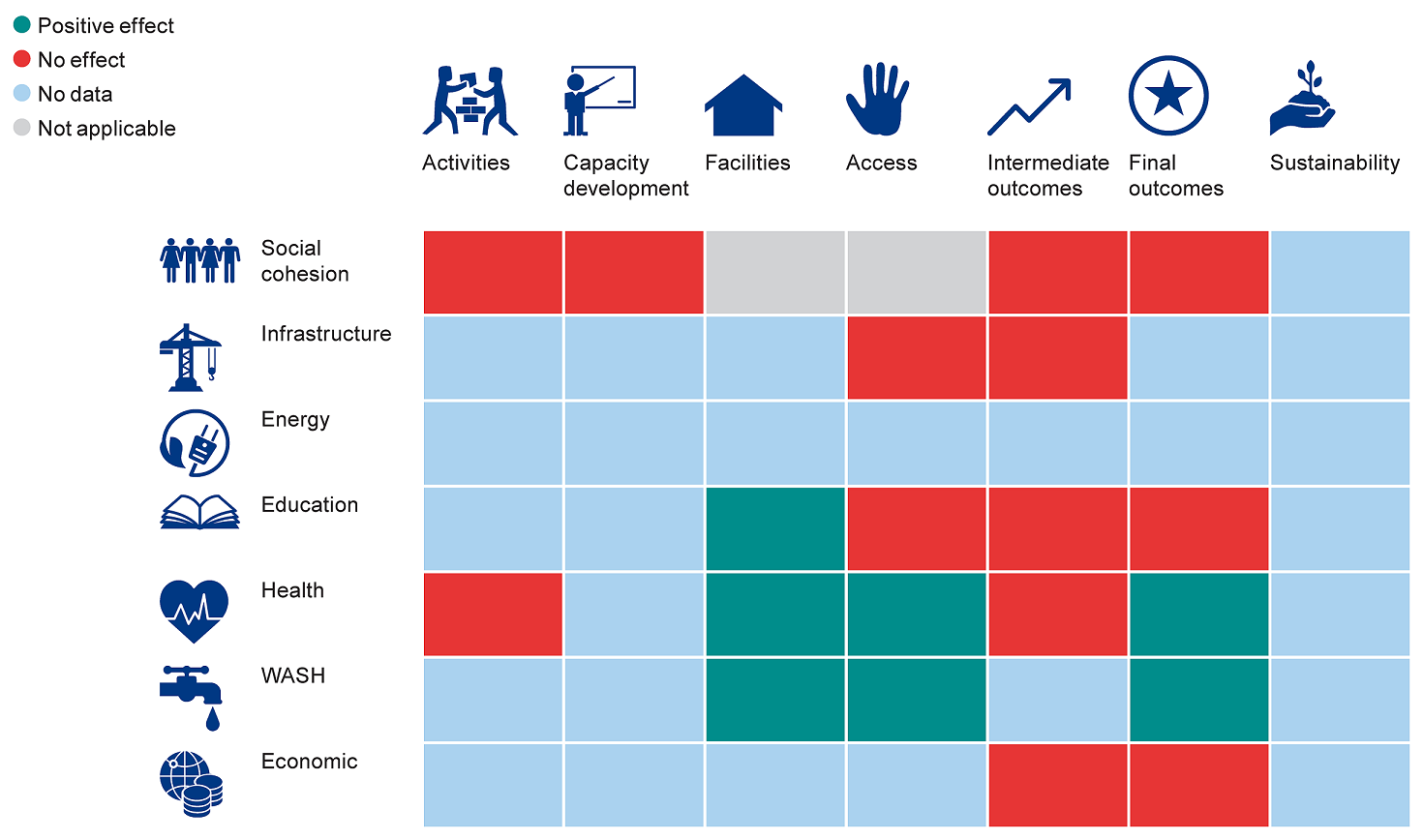

1. CDD programmes have substantially improved small-scale infrastructure

A large number of community projects, spanning vast geographical areas, has resulted in infrastructure creation—particularly for building or rehabilitating schools, health centres, WASH facilities, roads, and rural electrification.

2. Social welfare is not significantly impacted

CDD programmes have a weak effect on health and economic outcomes, and mostly insignificant effects on education and other markers of welfare.

[quote]CDD programmes have a weak effect on health and economic outcomes.[/quote]This finding is due, in part, to the ‘CDD impact evaluation problem’. This means, for example, when measuring the impact of the quality of health services across a number of treated communities—including those where no investments in health were made—the outcome is diluted.

That being said, there was a noticeably positive impact on WASH, with more time savings, and improved access to water supply and sanitation.

Figure 1. Overview of effects | Courtesy: 3ie

3. CDD has no impact on building social cohesion

The study found that CDD programmes have no impact on social cohesion, decentralisation, or governance. CDD did not aid with building trust and cooperation between community members, increasing social connectedness (particularly with authority figures), or encouraging greater participation in decision-making and political processes.

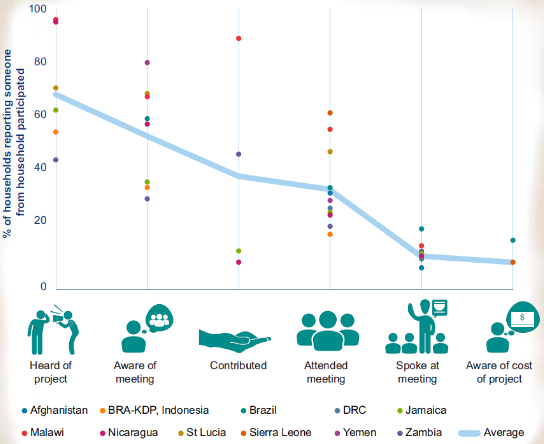

This is largely because the assumption that the entire community participates in CDD is not valid. Decision-making is actually limited to a small number of people, and a clear ‘funnel of attrition’ can be observed.

Figure 2. The funnel of attrition | Courtesy: 3ie

CDD programmes use existing social cohesion to carry out programmes, rather than using programmes to foster and build social cohesion.

[quote]Programme design can unintentionally favour the elite in the community.[/quote]Numerous factors affect community involvement. For example, the programme design can unintentionally favour the powerful elite in the community (by virtue of them being able to be more involved); intra-community divisions sometimes prevent the larger community from coming together; cooperation from local leadership could be met with difficulties; and community participation often depends on whether or not members personally perceive the benefit of participating.

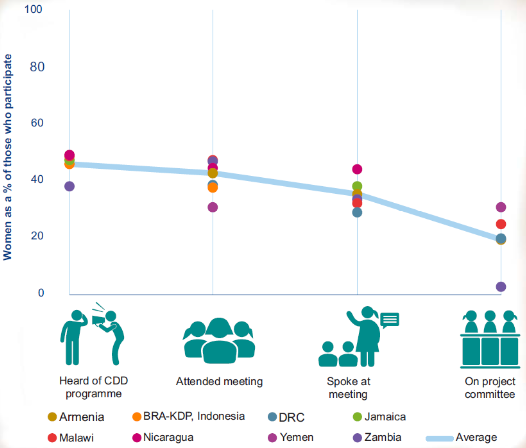

4. Measures to improve the participation of marginalised groups don’t always work

Most CDD programmes incorporate measures to encourage women’s participation in project identification, and on project committees. The assumption was that by engaging in these activities, women are more likely to benefit from supported projects, but there is no evidence on the impact of these measures.

Related article: IDR Interviews | Sujata Khandekar

Unfortunately, gendered cultural norms and socio-economic factors powerfully and negatively influence women’s participation in the public sphere. Available data show that women are only half as likely as men to be aware of CDD programmes, even less likely to attend the community meetings and subsequently, even less likely to speak at the meetings.

Figure 3. Participation of women | Courtesy: 3ie

5. It is unclear whether CDD programmes are cost-effective

The cost advantage of CDD approaches may be present but remains unproved. The available evidence suggest that local government is systematically cheaper, but this varies, depending on context.

Often, many institutional and financial mechanisms for project maintenance are put in place, but doing so has its own set of challenges—limited community capacity, recurrent expenses that aren’t always met, and more. Sometimes parallel structures are created for the sake of the programme, and the function of these governance structures is not clear once the community projects end.

The way forward for CDD policies and programmes

- The evidence from this synthesis and previous studies suggests that it may be better to abandon the CDD programme objective of building social cohesion and focus instead on sustainable, cost-effective delivery of small-scale infrastructure.

- Programme implementers need to assess whether community members are willing and able to make contributions to development projects.

- Moving beyond the definition of a community as a geographical administrative unit and considering different groups and gendered power relations in the community is important for delivering more equitable programmes.

- Since small-scale infrastructure is a major programme output, implementers should pay explicit attention to the technical, institutional and financial mechanisms in place for ensuring that these facilities are maintained and operate properly.

- There need to be more process evaluations and more qualitative research that examines why and for whom programmes work and do not work at each stage of implementation.

It would be inaccurate to proclaim that CDD either works or doesn’t work. CDD is multi-faceted—it may work in some areas, and may fail at others. When evaluating whether a CDD programme should be implemented or not, it is important to keep in mind that this is simply a tool for development that involves the community, and not a social movement that can underpin mindset change.

(There has been much debate over 3ie’s report on community-driven development (CDD). Duncan Green published a post that sparked a larger conversation around CDD, and drew in CDD experts into the narrative. 3ie consequently published a blogpost of their own in order to move the debate further, and even took to Twitter to do so, with the hashtag #3ieCDD)