My first experience with nutrition in Melghat was in 2019 when I went to a village and tried to assess a child for severe malnutrition. The mother couldn’t understand what I was saying and vice versa, but she gave me her child as she listened and nodded intently. While our smiles connected us, I was also aware of how much I was missing. In my three years at Melghat I realised just how much a short Korku sentence, “Kaaki, aama jum chui?” (Kaaki, what is your name?), could do. It gave me an entry to women’s houses, and while they still thought of me as an outsider, I was a little less so now.

Home to more than 75 percent of Korku Adivasi communities and vast forested terrain, Melghat in Amravati district, Maharashtra, is replete with tales of kula mama (tiger) and bhumkas (local healers). And though it has many lessons to teach the world, what its landscape is dotted by are stories of malnutrition.

When we at the Integrated Tribal Development Project, an office looking at development issues and strategies for Adivasi communities in the district, began understanding this issue in detail, we worked with the following assumptions: We knew that malnutrition affects both the rich and poor in many ways, and therefore getting the context right was crucial. We were aware that this needed fundamental interventions and would invariably be a long-term, incremental learning affair. We were crystal clear about the fact that it was essential to get every stakeholder to the table and find strategic areas on which to focus. This article documents some of the insights from our work in the field—shaped by the challenges and opportunities of COVID-19—that might find use in similar geographic or policy situations.

1. Use local-level data to drive action

As field officers, we often become transmitters of data instead of users. In doing so, we lose opportunities to change things in our context, imagining that someone is out there analysing and generating insights from our data. State-level or district-level comparisons cannot and must not substitute local-level analyses. While localised data is an important input in higher-level policymaking, we must also ensure that it is used by local teams.

For us the Integrated Child Development Scheme–Common Application Software (ICDS-CAS), which used to track Anganwadi-level malnutrition data across the country, did not always work. This is because uploading data to the system requires good internet connectivity, which many Anganwadi workers in our sub-division lacked. Incomplete data did not give us a holistic picture of malnutrition in the area, and therefore limited our ability to plan policy in a contextual manner.

Therefore, we decided to move to a lighter but more complete system of data collection, even if it meant ‘regressing’ to manual, Excel-based systems in some areas. We chose a few crucial indicators for the bare minimum data that must reach us from all Anganwadis. This exercise allowed us to understand which areas to focus on, areas where we could easily improve indices to set an example, as well as identify high-risk areas where urgent attention was needed. Our energy was focused on getting this information right so that we could construct local knowledge and act on it.

Timing, frequency, sampling, and methodology are all crucial in data reporting for malnutrition.

In the process of gathering and engaging with this data, we also found data discrepancies between various government sources and our data. The National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) data for our district showed different numbers from what we had recorded. To cross-check our data, we ran another survey in collaboration with nonprofits in the district. The mismatch still existed. While NFHS-5 indicated severe wasting of around 12 percent in the district, the third-party survey for our sub-division put this figure at around 3.5 percent, and our own figure was around 1 percent. This made us realise that timing, frequency, sampling, and methodology are all crucial in data reporting for malnutrition, especially for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) since it shifts constantly. All three surveys differed on these fronts: Our data was generated monthly and covered the whole sample, the third-party survey was done biannually for a large portion of the sample, while the NFHS took place once every 3–5 years for a relatively small, representative sample. The geographical disparity is also important. For example, NFHS generates data for a district. But considerable intra-district variations may exist, especially for areas like Melghat, which is merely one-seventh of the administrative area of the district but most important in terms of malnutrition.

Our key takeaway from this exercise was that constant monitoring is key. It is important for local field-based administrators to conduct robust, micro-level, third-party surveys at least once a year to understand the direction in which initiatives are going.

2. Communities, governments, and nonprofits need to work together

We set up Trialogue Melghat, a platform to unite the community, nonprofits, and the government. Malnutrition is a complex issue that the government cannot, and should not, tackle alone. Especially in a difficult geography like Melghat, it is important to work together. Community engagement is a strong indicator of how successful programmes can be, and civil society organisations bring in many synergies, both in terms of resources and building people’s trust. These organisations helped us take behavioural messaging to people, understand the needs of the community better, and convey information or grievance redressal communications.

During the pandemic, this informal network continues to work together to tackle multiple issues. Besides supporting us with infrastructure and communication, the group became a source of information for what is happening on the ground, whether in nutrition or MGNREGA. Since communication was seamless, we could reach out to our civil society partners any time we faced a bottleneck we weren’t able to solve. Through a simple WhatsApp group, we would immediately hear about someone not getting MGNREGA work, a migrant wanting to come back, or any child or patient needing immediate attention. As a result of this collaboration we could reach many more people, even in the most remote parts of the district.

3. Choose how you want to talk to people

Decentralising health, an idea that we believed in, involves empowering people directly. Breastfeeding is critical to improving the low birth weight of a child and we needed to teach women proper breastfeeding skills. For something as intimate (and crucial) as breastfeeding, we believed that women should have support available in their own private space. But how do we do this if we don’t speak the same language?

This birthed our Korku language project. Spoken Tutorials, a project initiated by IIT Bombay, created simple yet engaging videos on breastfeeding techniques, holds, and latches in line with WHO guidelines. The scripts of these videos were available in Hindi, and we converted these into Korku. This made Korku the first indigenous language in which these tutorials—available in 13 national languages and four international languages—were translated and used by fieldworkers and mothers. This made all the difference to how mothers engaged with the videos.

An equally necessary dimension of this process was training our fieldworkers to use these videos because they meet with people day in and day out. Their field skills also require constant updating and they need to be motivated. But often most of what passes for training are largely unidirectional monologues. If there are faults, they are with the trainees—who are ‘not educated enough’ or ‘not skilled enough’— and not with either the trainer or the training. We saw the need to fix this. And so most of the training we started designing with IIT Bombay included pre- and post-training tests on basic nutrition questions, which got progressively more difficult. The training also had to be made fun, and so doctors spoke about their own nutrition, and many of us realised that we need training too! The difference in engagement was for all of us to see, as our ground staff was much more lively, inquisitive, and active.

4. Use data to distinguish the urgent from the important

Children with SAM are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to malnutrition. To tackle the issue holistically, we need to make a dent in the fundamental nutrition of each child, aim to reduce anaemia and low birth weight, and improve the daily fitness of both mother and child. For a child’s nutrition the first 1,000 days are the most important, of which the first year, the first month, and so on are of increasing importance.

To this effect, we launched a child tracking project where our fieldworkers each ‘adopted’ five children from their primary healthcare centre (PHC) and monitored their weight once a week. This was a manageable task for a single fieldworker and it allowed us to build scale into what we were trying to do. Many fieldworkers were Korku themselves, so the translated videos also helped them learn the techniques and show them to mothers. The next step was to teach them to triage, that is, separate the children in need of urgent support, from the not so urgent and then focus their energy on training and following up.

Through the process, we realised that for such projects to be sustainable and flourish, they need constant dedication and energy. Many times, what failed us was not an absence of data—there is plenty of data generated at the PHC-level—but a lack of understanding of data. Field staff are often so busy collecting and entering data, that the analysis gets overlooked in the process.

Bad data is worse than no data because it adds work without any tangible benefit and can often be misleading.

Here it is worth emphasising that bad data is worse than no data because it adds work without any tangible benefit and can often be misleading. Sometimes, even though fieldworkers did their work diligently, they got caught up in administrative work. The local leadership, apart from maintaining an optimum work distribution, must also teach fieldworkers basic organisation skills that can make their regular work easy and less physically or mentally taxing. For instance, identifying digital tools to simplify the survey process, having fieldworkers use mobile platforms with inbuilt analytical tools instead of laptops, and automatic colour coding in Excel sheets are all tasks a digitally trained nodal officer can support with. These can go a long way in helping a well-intentioned administrator make data-driven decisions in the field.

5. Find interrelationships with other sectors

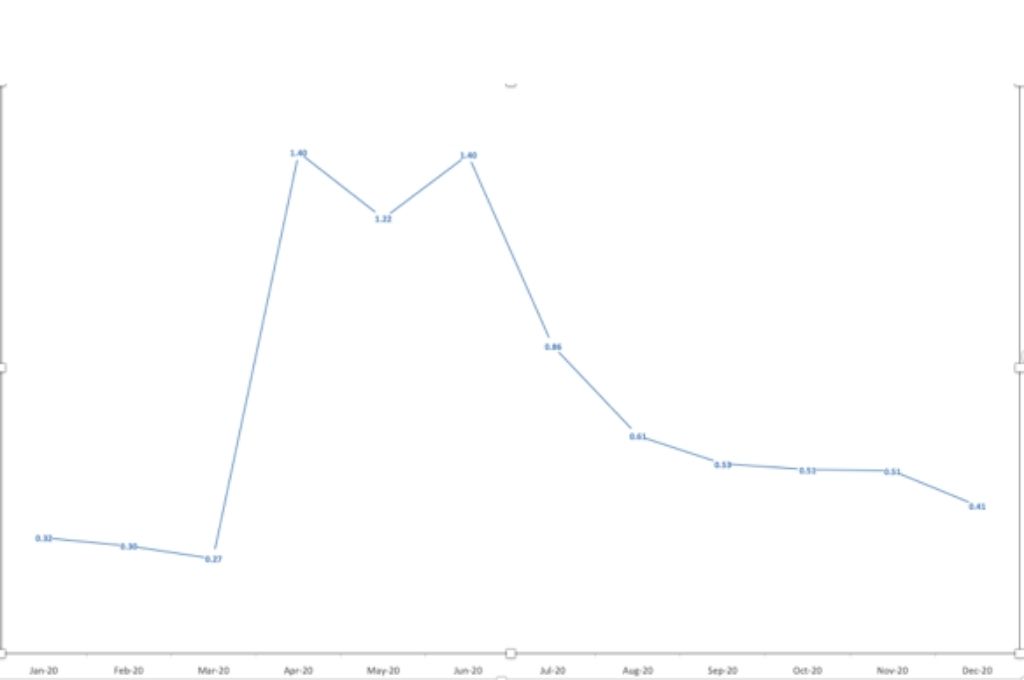

An unexpected benefit of our work on the ground has been getting answers to questions that we weren’t even asking. We noticed, for example, that on a seasonal basis ‘out of station’ was showing up in our data that tracked malnutrition. When we looked at the corresponding SAM data, a fascinating dynamic came to light. We saw an M-shaped graph of SAM numbers, which peaked when children returned with their families from the temporary jobs their parents had taken up as manual labourers in other blocks or districts.

We realised that many children, when they migrate, fall through the net of schemes—a significant problem when it comes to immunisation and health.

To address this, we focused on two things: the integration of schemes across geographies and strengthening MGNREGA to prevent migration. First, we coordinated with the neighbouring district of Akola—where a number of migrants were moving for work—to ensure that they conducted health check-ups and vaccinations for children. While we need to do more research to establish co-relation or causation between the two, we noticed that in March 2021, we did not see the annual peak in SAM numbers when families returned to Melghat.

Simultaneously, in 2020–21, Melghat generated its highest person-days in the last five years (or more) under MGNREGA. Though a step in the right direction, we are aware that we cannot give work to everyone, and some distress migration is inevitable. Therefore, we started work on designing a digital system that would help the source and destination of migration to get in touch with each other for benefits. This experiment was taken up by the state and the system—called Maha MTS (Maharashtra Migration Tracking System)—is being piloted in five districts of Maharashtra in 2022.

All these interventions—medical and administrative—will, of course, take time to show results. Our aim is to build these practices into the habits of fieldworkers and give them proper tools to handle the situation themselves, so that eventually we can institutionalise these changes.

The way we look at nutrition has to be much more than piecemeal, much more than just a department. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life depends not only on what they are eating, but also on their parents’ livelihoods, the skill of health workers around them, the infrastructure available in the community, the education they get about the world, and so much more. In areas that face critical malnutrition, the more local our solutions are, the better; the more contextual, the better; and the more decentralised, the better.

The views expressed in this article are personal.

—

Know more

- Read more about how the rural employment guarantee scheme (NREGA) and forest rights laws can come together to secure the futures of India’s forest communities.

- Learn more about the Maharashtra government’s pilot project to track and monitor inter-district migration, so that migrant children do not fall off the safety net of welfare benefits.

Do more

- Connect with the author at healinghandmeet@gmail.com for comments, feedback, and suggestions.