Domestic philanthropy in India is expanding rapidly, driven by the growth in individual and corporate giving. Between 2011 and 2016, social sector funding in India grew at an annual rate of nine percent, from INR 145,960 crores to INR 218,968 crores. This upward trend is largely driven by the growth in domestic individual philanthropy, which is the second largest source of social sector funding in India after government spending. The CSR mandate of the Companies Act, 2013 has helped in the rise of corporate giving.

Increasingly, philanthropists are focusing their giving on addressing specific social change issues. Their approach to giving has transformed from the more conventional ‘chequebook giving’ to thinking strategically about how to achieve better outcomes in society. They define clear goals, set out a pathway for change, and put in place mechanisms to measure progress and results. Some are tackling deeply entrenched social challenges to help create population-level change in areas of large social need.

Philanthropists have moved from ‘chequebook giving’ to thinking strategically about better outcomes.

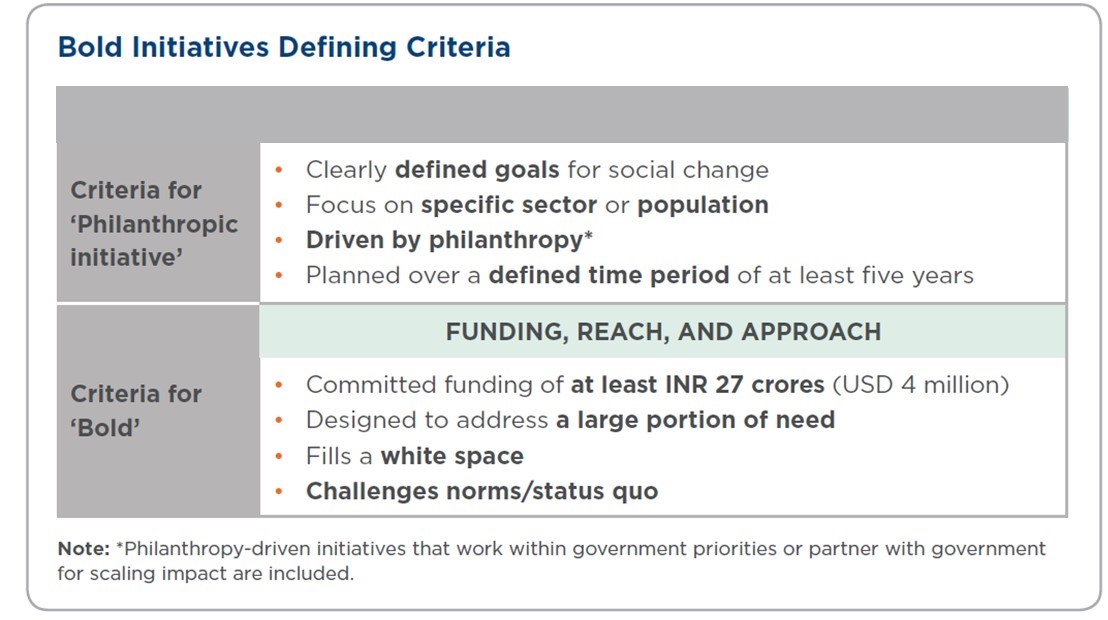

This type of ‘bold philanthropy’ has been gathering momentum in India, but there has not yet been all that much written on the subject. For its new report—Bold Philanthropy: Insights from Eight Social Change Initiatives—The Bridgespan Group examined nearly 100 philanthropic initiatives in India, and chose eight that were determined to be bold on the basis of several parameters: giving size, clear social change goals which deliver population-level change, white space of unmet needs, and a clearly defined pathway toward addressing a seemingly intractable social problem.

The report shares insights from these examples and highlights challenges and lessons learned in order to inform and potentially inspire other Indian philanthropists who might be inclined to give boldly for social change.

Courtesy: The Bridgespan Group

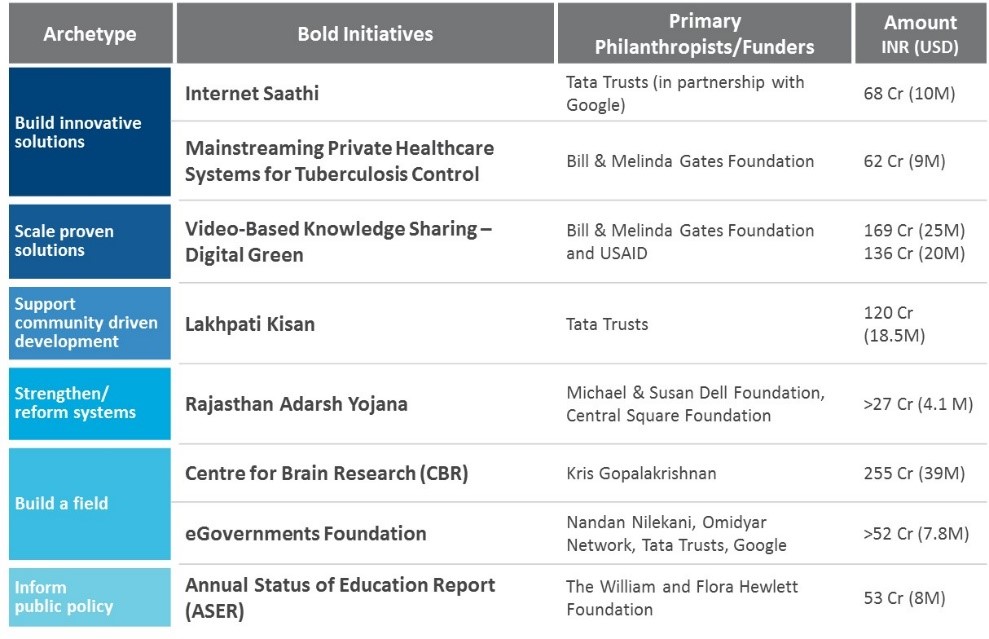

The report’s eight initiatives fall under six identified archetypes of giving—which may go beyond the Indian context and be thought of as global archetypes of bold giving.

Related article: What has CSR really achieved?

The six archetypes of bold philanthropy | Courtesy: The Bridgespan Group

1. Build innovative solutions

This type of giving seeks to disrupt status quo approaches in order to develop novel initiatives, and demonstrate potential for impact at scale. Efforts could include innovative market-based models or technology-based solutions that accelerate behaviour change.

Internet Saathi: A large majority of rural women in India lack access to the internet, and miss out on a host of digital social services and opportunities to improve their economic conditions. Google and Tata Trusts’ digital literacy initiative, Internet Saathi, aims to bridge the digital divide by training rural women to access the internet through smartphones. These women, or Saathis, then travel from village to village, passing on their knowledge and expertise.

The impact appears to be both social and technological. A 2017 study by IPSOS, a global marketing firm, found that over one-third of women who attended trainings reported enhanced economic wellbeing on account of these Saathi trainings. In the three years since the initiative’s launch, more than 15 million women have benefitted across 17 states of India.

Key learnings:

- Use philanthropy to test high potential but risky solutions that others would not consider

- As on-the ground conditions change, evolve the initiative’s approaches for deeper impact

- Build partnerships based on common values and goals but distinctive capabilities

- Engage champions in the community to increase the initiative’s scale and deepen its impact

More than 15 million women have benefitted across 17 Indian states | Photo courtesy: Womenwill

2. Scale proven solutions

The basic premise of scale is to identify existing interventions that are working, and extend their impact to new geographic areas or target groups. This could mean retaining some of the essential elements of the intervention, while customising others to accommodate changing conditions where the impact is being scaled. Scaling could involve collaborating with nonprofits, governments, the private sector, and multi-stakeholder partnerships.

Digital Green’s Video-Based Knowledge Sharing: Farmers’ income, health, and welfare depends on getting timely information on good agricultural practices. There are networks of agriculture experts and frontline extension workers who disseminate knowledge to farmers in order to improve crop yield, and prepare for food supply shocks and natural disasters. But these networks are time-consuming, resource-intensive, and difficult to scale.

Digital Green, with initial support from Microsoft Research, and then the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, piloted a model in 2008 to produce and disseminate instructional videos featuring local farmers describing high-yielding practices. They deliver their video-based model through existing government agriculture-extension systems (National and State Rural Livelihoods Missions in India, and Ministry of Agriculture & Livestock Development in Ethiopia), and government-employed video production teams create locally relevant videos that are screened in villages. To date, three controlled trial studies have found that this video-based approach drives higher adoption rates of farming best practices compared to traditional agriculture extension systems. For example, In Karnataka, the initiative helped smallholder farmers adopt best practices at seven times the rate of traditional systems.

Using innovative technology and working through government systems to spread more cost-effective practices, the initiative has scaled its reach to 1.9 million smallholder farmers globally, and is now expanding its focus to include dissemination of health and nutrition best practices to remote populations.

Key learnings:

- Invest philanthropic capital in piloting innovations and scaling what works

- Use technology to help frontline workers deliver and scale programs more effectively

- Tailor messaging to maximise engagement and motivate behaviour change

- Identify and partner with government entities that have wide reach and share similar goals in order to scale

- Continuously refine, adapt, and build on a model to accelerate its impact

Related article: Scaling—How to go from x to 10x

3. Support community-driven development

Community-driven development (CDD) involves collectively working on a social problem from the bottom up, and thoroughly understanding a community’s needs. The approach requires knowledge about the community’s demographics, political economy, socio-economic conditions, behaviours, and preferences. CDD needs to be fluid to suit the community’s specific needs.

Lakhpati Kisan: Almost half of the scheduled tribes in rural India live below the poverty line, and around 65 percent are landless. Tata Trusts, in association with Collectives for Integrated Livelihood Initiatives (CInI), launched the Lakhpati Kisan initiative, aimed at making more than 101,000 tribal households ‘lakhpatis’. The initiative envisions that by 2020, each of its target households would earn more than INR 120,000 per annum, the estimated amount to keep rural families from slipping back into poverty.

Since its inception in 2015, Lakhpati Kisan has reached more than 100,000 households across 800 villages in the Central India Belt, and 20,000 households have reached their target INR 120,000 threshold.

Key learnings:

- Mobilise around a clear and meaningful goal

- Empower the community to lead

- Involve the doers in the decision-making

- Collaborate with broader ecosystem of funders and partners for greater impact

- Adapt continuously and course-correct based on realities on the ground

Related article: Does bottom-up development work?

4. Strengthen and reform systems

Long lasting change can be achieved by influencing the underlying structures, relationships, and beliefs that characterise a social ecosystem. This usually involves developing insights into how a system operates, how various actors interact, and the best way to coordinate the efforts of diverse stakeholders.

Rajasthan Adarsh Yojana: Until very recently, Rajasthan’s public education system was one of the country’s poorest performing. In 2014, the state government came up with the Rajasthan Adarsh Yojana, an ambitious initiative that would establish an adarsh (ideal) school in each village cluster across the state. These schools would provide high-quality education and serve as a model for all other state public schools.

The Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, with technical support from the Central Square Foundation (CSF), invested in the initiative, which seeks to improve the quality of education for 4.6 million students in 9,895 government schools across Rajasthan. Since its launch in 2014, Rajasthan Adarsh Yojana has converted nearly 95 percent of the designated schools to the adarsh model. Teacher vacancies in those schools have dropped from about 50 percent in 2014 to 20 percent in 2017.

Key learnings:

- Collaborate effectively with key government stakeholders for systemic change

- Focus on strengthening administrative infrastructure, which provides a foundation for other reforms

- Build the system’s capacity to sustain change

- Use data to support behavioural change at multiple levels

5. Build a field

Building a field involves investing in efforts to fill a gap, or bringing together stakeholders pursuing the same problem. Activities may include building the capacity of leaders and institutions, developing a knowledge base, and creating an intermediary that supports other actors in the field.

Centre for Brain Research: It is estimated that more than 30 million Indians live with some type of cognitive disability, and the incidence of neurological disorders in the country continues to grow. But India lacks the research infrastructure that could support large-scale exploration into brain function and genomics.

In 2014, Kris Gopalakrishnan launched the Centre for Brain Research (CBR), one of the only institutions in the country focusing on long-term, longitudinal research to understand how the brain ages and conducting clinical neuroscience studies focused on brain disorders among the Indian population. CBR’s first project addresses ageing-related brain disorders. CBR is a critical field builder, and emphasises collaborative public-private partnership within and outside India to further its mission.

Key learnings:

- Use philanthropic funding as risk capital to seed less-funded initiatives

- Fill knowledge gaps that catalyse efforts across the field

- Collaborate with partners to accelerate progress

6. Inform public policy

These types of efforts provide focus on shaping legislative, administrative, and judicial reforms. Activities may include developing an evidence base through research, producing policy briefs, and mobilising stakeholders to support a cause.

Annual Status of Education Report (ASER): Until recently, educators lacked conclusive data on whether better attendance led to more learning. The ASER Centre’s nationwide annual survey, a product of collaboration between the Hewlett Foundation and Pratham, takes a radically different approach from other learning assessments. Volunteers conduct surveys orally within families’ homes, thereby accounting for all children, including absentees and unenrolled children.

The discourse has shifted from focusing on enrolment rates to improving learning outcomes | Photo courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

Through its pioneering approach, ASER is using data to make starkly evident the extent of India’s education crisis. This data has shifted India’s national discourse from focusing on enrolment rates to improving learning outcomes.

Key learnings:

- Use philanthropy to create an evidence base and drive advocacy efforts around an issue

- Develop novel and inclusive tools when existing ones do not serve your purpose

- Continuously experiment with new approaches to addressing a problem

Much of philanthropy in India is willing to invest capital patiently in order to help the country achieve its long-term social goals. Whilst bold philanthropy clearly involves risks, small, cautious efforts can rarely drive population-level change.