“What does the colour of this butterfly’s wings tell you about its life?”

My question travelled through the group of students. Curiosity is a skill, and I’d kept this in mind when I decided to initiate the first science walk in Dharmanagar, my home town, with a few of my students in 2024. The goal was straightforward—to engage the youth in understanding nature through curiosity.

Each year in September, which is the Big Butterfly Month, thousands of nature enthusiasts and citizen scientists (civilians empowered with tools to conduct scientific experiments and data collection) across the country throng to their neighbourhood forests looking for butterflies. Armed with binoculars, field guides, apps like iNaturalist (used to log nature observations), and a keen interest in nature, these citizen scientists have helped turn the month into one of the most successful citizen science initiatives worldwide. This happens to be among the numerous science initiatives currently operational in India, and represents a rising wave of citizen scientists in the country. However, like most development initiatives, it isn’t evenly spread across the numerous states and districts that make this country.

In this context, the case of the Northeast is interesting because the communities living in these states have a long history of ecological knowledge and conservation, and a willingness to invest in intergenerational exchanges. The success and popularity of events like the Big Butterfly Month is proof that there is interest in science among the people. But a lot more needs to be done to turn this interest into meaningful impact.

As we observed the swallowtails and commanders in the undergrowth, Rabbani, a young student, asked, “What can we deduce about the ecosystem from these butterflies, sir?” I reckoned every one of them must’ve thought about this at some point during the walk. We walked on and I explained how butterflies act as bioindicators (a species whose presence at a place suggests high biodiversity) for ecosystems and shared other interesting facts about them. But then Saumya, another student, asked a question that got me thinking:

“Just like how butterflies cannot thrive without ecological balance, we humans too need a stable set of networks to rebuild our connection with nature and the planet, isn’t it?”

The system is only as resilient as the interactions that build it

Ecology is a highly non-linear science. Environmental ecosystems depend on several subtle factors for survival and evolution. A tiny missing factor can cascade into decisive outcomes for ecosystems. For example, stray dog poisoning in Assam led to the death of vultures, but the impact doesn’t just stop there. Vultures are scavengers who feed on animal carcasses; their absence can lead to major sanitation crises, causing health complications in humans and deaths. Similarly, the destruction of wetlands due to industrial expansion can increase flooding because wetlands absorb excess rainfall.

These are webs of complex interactions that bind living and non-living beings into a network and decide the health of ecosystems. All of this simply means that the system is only as resilient as the interactions that build it. Therefore, it is important to understand these links.

When we consider the northeast Indian landscape, the sheer richness in biodiversity necessitates a strong sense of kinship between indigenous communities and their environments. Poorly planned development initiatives, loss of traditional knowledge, and human greed can derail the fragile ecological balance. Thus, there is an immediate need for documentation of community knowledge and strengthening of community-led conservation through wider civil society participation in science. However, this isn’t possible without institutional support from government bodies and civil society groups. For example, popular citizen science projects in India such as Pune Knowledge Cluster (PKC) and Open Day in Bengaluru are organised by nonprofits, local governments, and educational institutions. In the Northeast, similar initiatives and region-specific projects will require the same kind of patronage.

Until then, existing environmental programmes in the region can attempt to fill the gap.

Curiosity is a skill, communication the hand that wields it

At Green Hub, an environmental film-making fellowship that I joined in 2023, I made films on ecology and human–wildlife interactions. An essential part of the process was research. With my background in physics, this was the easy bit. However, I realised that communicating science with people on the ground, who are its primary stakeholders, is crucial and also a major challenge. This is when the urgency of citizen participation in scientific research became apparent to me, and my work in Tripura has since aligned with this goal.

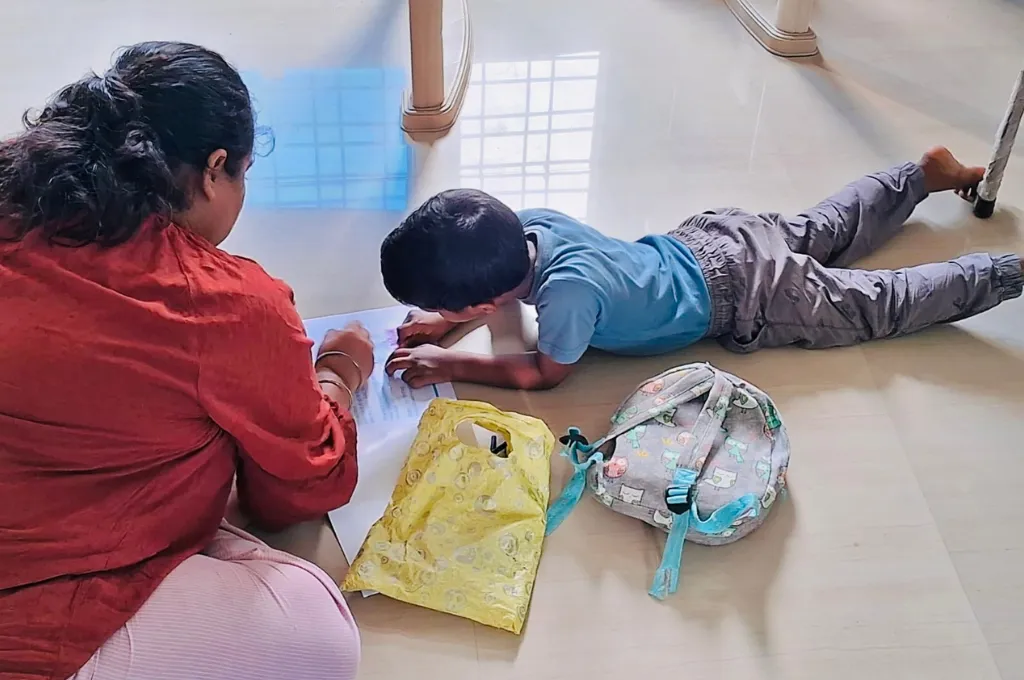

I have undertaken multiple science walks and outreach activities in Tripura and beyond, focusing largely on the youth. In Panicherra, a village in North Tripura, the science walks and moth screenings helped bring the local kids closer to their landscape through observations, mobile photography, and acoustic identification. Using basic equipment like blue lights and white sheets, I managed to set up a moth screen, which helped us understand the diversity of insects in the vicinity of rubber plantations. For my students, broader issues of habitat degradation and social ecology became evident through interactions with the community and slow, carefully curated observational ecology sessions.

At the district library in Dharmanagar, I have organised multiple open science discussions that generated awareness about science, policy, and diverse issues related to the region. All of this has been a validation of the power of curiosity and the urgent need for cohesive, community-led citizen science networks. After all, curiosity is a skill; communication is the hand that wields it.

Similarly, other Green Hub fellows have documented community cultural practices that provide a window into understanding sustainability in the region. For example, Thejavikho Chase’s award-winning film on edible insects in Nagaland records the widespread practice of insect consumption, highlighting an important connection between bioresources and their conservation.

For citizen science to flourish, an overarching organisational structure that sustains engagement and momentum is vital.

In the Northeast, fellowships like Green Hub can act as vital springboards for citizen science projects that combine the rigour of scientific research with the power of visual storytelling. This blend of science and storytelling can plug the science communication gap and also boost citizen science participation rates. Green Hub fellows are extensively trained in fieldwork, documentation, and storytelling across the full spectrum. Each fellow gets a granular insight into the art of communication, from research to storyboarding and stitching the story together on the editing table. But, due to limited resources, programmes such as these can only train youth to tell stories; more needs to be done to blend in a strong citizen science component.

For citizen science to flourish, an overarching organisational structure that sustains engagement and momentum is vital. Additionally, logistics can be a decisive factor in the successful implementation of projects. Not having the right equipment has forced me to use videos and simulations as stand-ins. Without a portable projector set-up, I’ve shown documentaries to inquisitive kids on my 13-inch laptop screen. Lack of a camera and additional equipment has forced me to make do with a phone camera and professional photographs. The absence of trained instructors compounds the fragmented institutional support. Without comprehensive plans and engagement, any project that involves citizens at a large scale can quickly fall through.

As a society, we need to urgently understand that the promotion of citizen science benefits the entire environment.

The need for democratising science

Citizen science takes research out of academic silos and democratises the scientific process, ensuring social participation and people’s stake in the larger policy landscape. Citizen scientists generate granular knowledge about contemporary societies that can serve as vital inputs for the policymaking process. As researchers Moumita Koley and Suryesh Namdeo write: “[It] can be used as an innovative way of data collection for research which otherwise would have not been possible or would have been too expensive to carry out.”

Civil participation can improve the democratic nature of policymaking, and as is evident from realistic assessments, citizen science must be treated as a vital pillar of public policy and governance.

The remarkable power of citizen science lies in its hyperlocal nature. In recent years, there have been many instances where citizen science has led to remarkable results.

- Hornbill Watch—a citizen-driven hornbill-spotting initiative run by Nature Conservation Foundation and Conservation India—has been a success story in the eastern Himalayan landscape. It has directly influenced the conservation of hornbills and their habitats. The fact that 430 citizen scientists generated 938 records covering nine hornbill species, including the endangered Narcondam hornbill, shows that this model works.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, PKC built a database of COVID-19 clinical data for more than 2,000 patients across the city, which helped healthcare professionals in tracking the disease. This hub-and-spoke model can be instrumental in bridging the gap between academic research and citizen scientists.

- At Earthwatch India’s water quality monitoring project, the nonprofit worked with citizen scientists to study urban lakes, wetlands, and green spaces with the objective of understanding their importance in the urban ecosystem. The citizens collected 7,000 data points that contributed to building the understanding of the researchers. CitSci India’s list highlights several projects targeting crucial sectors in environmental monitoring and human–wildlife conflict mitigation.

These are just a few of numerous initiatives, and therefore provide only a glimpse of how larger participation from youth and stronger storytelling can aid scientific policymaking and democratic governance.

In this world of rapidly advancing technology, accessing science should not be as herculean a task as it is. With the unprecedented rise in AI tools and big data, inference has become remarkably faster and more democratic in many parts of the world. Open-source software has widened the scope of citizen science beyond the ecological domain. For example, anyone can become an e-astronomer with India’s RAD@home project (a collaborative astronomy platform), which draws inspiration from the SETI@home project in UC Berkeley. This collaborative model of public research appears more feasible and effective with the increase in cheaper cloud computing architectures and a tech-savvy generation. Similarly, NASA’s public repository of open projects and toolsets can inspire and empower youth to participate in scientific research. However, there should be institutional efforts in regions such as the Northeast to spread awareness about these tools and their uses.

When people are empowered to use tools and techniques to understand the world in a structured, scientific manner, the dividends down the stream are nothing short of revolutionary. But the key is the tight integration of policy and action, and more democratisation of research. Equitable citizen science policies are essential for the Northeast to develop sustainably. A science walk may begin with a few steps, but I believe it will lead to a highly rewarding journey for us Northeasterners and the nation at large.

—