Findings from the first phase of the 5th National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) were released in December 2020. The data has highlighted the deteriorating nutrition status of children, and this narrative has occupied much of the public discourse. For the first time in two decades, children’s stunting (low height for age), and wasting (low weight for height) are seeing a worsening trend in several states. These are worrying trends that impact an individual child through their life and have macro-economic impacts on the country—an estimated cost of 0.8-2.5 percent to India’s GDP.

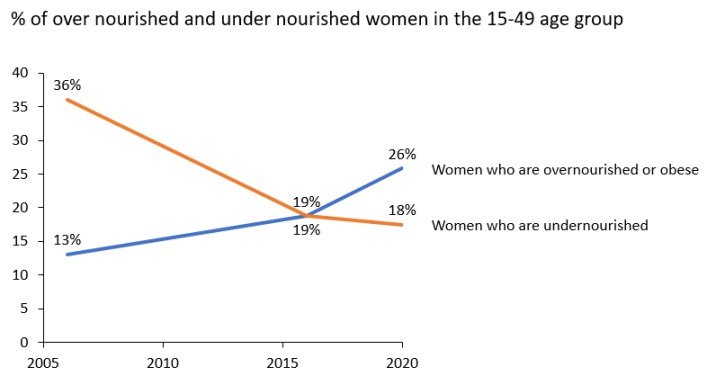

While this is a serious issue, there are other startling trends that affect close to 50 percent of our population that have gone largely unnoticed so far, lacking the critical attention they deserve. When we analysed data from 25 of the 130 parameters captured by the NFHS-5 in 18 states, we found that India now has more overnourished, than undernourished women. The same trend holds true for men as well, where the share of overnourished men had surpassed the share of undernourished men in 2016 survey itself.

From scarcity to abundance

For the first time in our recorded history, we have more overnourished (obese and overweight with a Body Mass Index or BMI of 25.0 or above) than undernourished (with a BMI of less than 18.5) women in the 15-49-year age group1.

In NFHS-4 (2015-2016), this trend was just beginning to emerge. The proportion of undernourished women (at 18.8 percent) was at par with the proportion of overnourished women in the 15-49 age group. This year, that difference has expanded to 8.4 percentage points. The first phase of NFHS-5 suggests that there are 48.4 million overnourished women, compared to 32.8 million undernourished women in the 15-49 age group. The data for men has followed a similar trend, where the gap between share of overnourished and undernourished men has increased from 3 percent in NFHS-4 to 10 percent in NFHS-5.

Studies have shown that maternal nutritional status influences pre-natal growth for the first two years

These findings are particularly alarming in the context of the debate and discussion around stunting and undernutrition among children. Studies have shown that maternal nutritional status influences pre-natal growth for the first two years, and that it is also a determinant of chronic and acute nutritional status in children under five years. In the context of these two emerging trends in India—first, overnutrition among women and second, wasting and stunting among children—there is an opportunity to look more closely to understand any possible linkage and causality.

What are some of the reasons for this shift?

It is worth noting that much of this obesity is present in urban areas. Thirty-three percent of women in urban areas are overnourished, as against 21 percent of rural women. Overall, 49 percent of all overnourished women are from rural areas, although this may be attributed to a higher total population size. The trends among men are similar—30 percent of men in urban areas are overnourished, compared to 22 percent rural men. Fifty-three percent of all overnourished men are from rural areas.

Awareness about obesity in India and its ill-effects is perilously low.

Explanations for obesity revolve around well-understood shifts in the consumption basket and lifestyle that are driven by the complex interplay of changes in taste, aspiration, and convenience. Over the last two decades or so several factors have changed. Rapid economic development has seen dietary patterns shift towards energy-dense foods, which together with increased urbanisation and an associated sedentary lifestyle have contributed to the rise in obesity. Access to processed food has changed—snacking used to be fresh food made by a street-hawker, whereas now fast food is both aspirational and convenient. For instance, in India, the overall per capita sales of packaged and processed foods nearly doubled from USD 31.3 in 2012 to USD 57.7 in 2018. Finally, awareness about obesity in India and its ill-effects is perilously low. Anecdotally, through conversations, it has been observed that many people think of high cholesterol and high blood pressure as the cost of growing old, and not something that they have control over and which is associated with their diet and lifestyle.

How is this likely to affect health?

One of the biggest impacts of overnutrition is the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in India. Obesity leads to an increase in underlying factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high fasting glucose that essentially contribute to NCDs such as cardiac ailments, cancer, and type 2 diabetes. It is worth noting that between 1990 and 2016, NCDs’ contribution to India’s mortality burden increased from 37 percent to 61 percent. India is also the diabetes capital of the world, with over 50 million diabetics as of 2016. Our health system will need to adjust in order to accommodate this growth in NCDs vis-à-vis transmissible diseases.

In response to this, the government has started to take steps to address the rise of NCDs. One example is the planned roll-out of 150,000 Ayushman Bharat health and wellness centres. These clinics provide an expanded range of services that includes ambitious offerings to screen, prevent, control, and manage NCDs. However, the concept is only about two years old and the on-ground impact is still to be understood. State governments are also implementing programmes for NCDs as part of the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS). While these programmes clearly articulate an understanding of the growing problem of overnourishment, an assessment of the programme delivery in some districts suggests that implementation is lacking, with limited outreach and out-patient-department (OPD) activities. There is plenty of room for healthcare actors (government and private) to increase the scope of interventions at their end.

Players can also explore more preventive health programmes (increasing awareness drives and diagnostic screenings) as well as increased treatment capacity. Hospitals will need more beds, as well as more treatment for cardiac care, oncology, and certain orthopaedic ailments that are closely associated with obesity. To make this happen, the government will also have to:

- Strengthen its public-private partnerships in healthcare

- Reinforce Ayushman Bharat (insurance) programmes

- Explore viability gap funding mechanisms to enable large scale participation by private players in Tier-II and Tier-III cities, as well as rural settings

Further, in order to reduce the incidence of obesity, there needs to be a huge mindset change around diet and lifestyle issues. Many of our government and civil society programmes—including those for children, such as the Midday Meal Scheme, Poshan Abhiyan, and Integrated Child Development Service (ICDS)—were all built to solve the problem of chronic undernutrition that plagued India. Therefore, they have tended to focus primarily on increasing and supplementing nutrition. This focus on calorie intake has carried over beyond these government programmes to everyday life where Indians tend to prefer grains (rice, wheat) for their calories. For instance, Indians should be getting 850 calories from carbohydrate sources, but we get 1,200 from them and instead of the recommended 900 calories from protein, we only get 310 from this source.

What do governments and civil society need to do now?

The factors that drive these shifts are complex. For a long time, Indians needed more calories—and the public distribution system and consumption in India has focused increasingly on grains like rice and wheat to meet this need, particularly post the Green Revolution. But at the same time, it is also important to remember that obesity is itself a form of malnourishment, characterised by too much energy intake in the way of ‘bad calories’ that don’t necessarily contain the right nutrients and can lead to adverse health impacts.

Government response to this growing surge of obesity must be comprehensive and inter-sectoral.

Government response to this growing surge of obesity must be comprehensive and inter-sectoral. Getting the messaging right is particularly challenging for countries like India, where the problem of undernutrition still persists, in what the World Health Organisation calls the ‘double burden of malnutrition’. Here, the government would not want one message to muddle the other.

In such a scenario, governments can explore a three-pronged approach. This includes:

- Policy and regulatory interventions at a macro level (eg. food labelling and tax incentives)

- Interventions around awareness and community participation (eg. awareness campaigns and helping to change lifestyle habits at workplaces and schools)

- Grassroots interventions aimed at building healthier habits from childhood (eg. physical exercise and health education)

Philanthropy and civil society can play a role in each of these three stages as well. At the policy level, there is room to create changes by working with business and government top-down to drive shifts away from aerated drinks, processed food, a non-diversified diet, and so on. At the local community level, there is room for large scale awareness programmes (like those on air pollution that philanthropy has championed) that explains the extent and implications of the obesity issue. Here, philanthropy can also piggy-back on some of the campaigns rolled out by the government (eg. #local4poshan, or the ‘Eat Right’ initiative launched by the FSSAI). Finally, at the grassroots, philanthropy can facilitate nonprofits to work one-on-one with decision makers to help drive the types of lifestyle and dietary changes that can improve household and individual nutritional status.

—

Footnotes

- BMI or Body Mass Index is one of the most widely used metrics to measure individual health and nutritional status by assessing body mass per unit of the individual’s height (squared). The metric is limited in several ways. For example, it doesn’t look at the distribution of fat, or the split of muscle and fat in a person’s body. Yet, it is one of the more convenient metrics with some level of universal acceptance.

Know more

- Read about how India is tackling the double burden of both obesity and malnutrition in girls and women.

- Learn more about why NFHS-5 data merits serious concern and urgent action.

Do more

- Connect with the author at [email protected] to learn more about her work.