Given the increasing buzz around Development Impact Bonds (DIBs) 1and impact bonds generally—both in India and elsewhere, we have seen and heard about the advantages they bring to the table: a result orientation in funders and nonprofits alike, an alignment in mission amongst them, increased accountability towards achieving outcomes, greater flexibility in the way money is invested in different aspects of the programme, and generally, more rigour to the whole ecosystem.

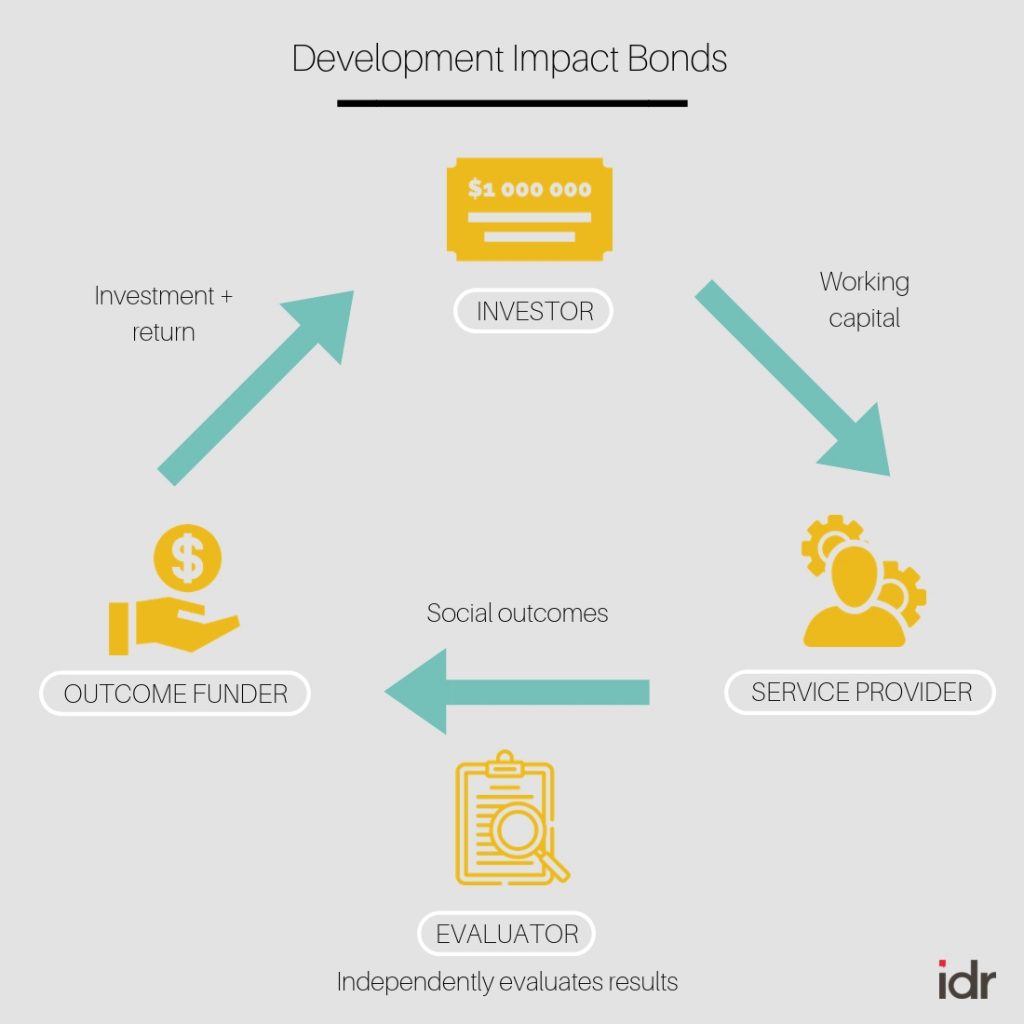

Source: IDR

An impact bond, for those unfamiliar with them, is a results-based financing instrument, where an investor provides upfront capital to a service provider towards achieving stipulated outcomes. Only if these outcomes are met, are the investors repaid their principal with some agreed upon interest by outcome funders.

From the point of view of an outcome payer—the government or a donor—impact bonds minimise financial risk, and encourage more private capital to be used for scaling interventions that show evidence of outcomes.

Overall at an ecosystem level, as the field for impact bonds develops, it will help build an evidence base about which interventions work, and a more detailed understanding around the cost of delivering programmes.

It’s critical that we understand which contexts, conditions, and sectors lend themselves to a successful DIB.

Because DIBs are a relatively new approach vis-à-vis traditional development funding, they also come with a number of challenges. Given how development is understood and implemented in our country today—low outcome orientation and challenges with governance and accountability—it’s critical that we understand which contexts, conditions, and sectors lend themselves to a successful DIB.

Related article: IDR Explains | Development Impact Bonds

Challenges associated with impact bonds

The structure of a DIB is complex given that there are multiple stakeholders involved, each playing a different role, and having varying levels of involvement and investment. DIBs also require a fair amount of effort in just management and oversight, making for high transaction costs. Funds must be spent not only on the intervention and its monitoring and evaluation, but also on managing multiple stakeholders throughout the project, which can span from one year to as long as 10 years.

The market for impact bonds in India is growing rather quickly with the successful completion of the first DIB by Educate Girls. The last year alone has seen the launch of two new DIBs, Utkrisht and Quality Education India, and the largest endeavour till date—the billion dollar India Education Outcome Fund.

However, unlike developed countries, India faces a significant challenge as the government so far has not supported outcome funding. Globally, of the 134 impact bonds spread across 27 countries, 95 percent have government outcome funders.2

Most government spending is input-based. The mindset shift from inputs to outcomes is critical.

The ideal situation would be one where the government pays for the results achieved because ultimately, there is no match for government funding and scale. But in the absence of considerable evidence—globally and in India—on the effectiveness of DIBs, getting the Indian government on board will take time. This is partly because most government spending today is input-based. Typically, a specific amount of money has to be spent in a specific year based on a pre-determined area of expenditure outlined in the budget.

The mindset shift from inputs to outcomes is critical; but more importantly, if impact bonds are to gain acceptance nationally, a change in policy and budget allocations will be necessary.

In the absence of the government as the outcome funder, trusts, charitable organisations, and development finance institutions have played a role. Even so, we have seen that it can be hard to get them on board as outcome funders.

Related article: How funders become their own enemy

This seems counter-intuitive, because one would think that if philanthropists are making grants anyway, why would they not want to just pay for outcomes? But we have noticed that in India and other countries, outcome funders generally want to be more involved with project design, the activities that the service provider (nonprofit) is undertaking, and how the overall project is managed on the ground. This presents challenges in a model that has a complex structure, is designed for unrestricted funding, and is geared towards greater flexibility and innovation in implementation.

The market for impact bonds in India is growing rather quickly with the successful completion of the first DIB by Educate Girls | Photo courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

So, does India offer an enabling environment for DIBs in the first place?

We believe that like with any approach, there are certain conditions that are more conducive to success, than others. Similarly, DIBs are no silver bullet; they have a greater chance of success when certain conditions are met. From our research globally and in developing countries, we have formed a core hypothesis around when it makes sense to design and implement a DIB.

In an impact bond, risk investors are only repaid upon achievement of a set of outcomes. Thus, given the high stakes, any ambiguity around defining and measuring a DIB’s outcomes would make the effort pointless. For example, an outcome such as ‘a change in attitudes among men towards violence against women’, while worth achieving, may not be best pursued through a DIB as it is not quantifiable. In the Educate Girls DIB, the two outcomes that were tracked were an increase in numeracy and literacy learning levels measured against the ASER test, and an improvement in girls’ school enrolment rates.

Rigourous evaluation of outcomes by a third party becomes critical. Additionally, clearly defining and measuring outcomes helps build the evidence base for which interventions work.

Related article: Funding education with impact

DIBs bring about an ‘outcome orientation’ in all stakeholders. Hence, an intervention where there is little difference between funding outcomes and inputs would not work well.

For instance, it makes little sense to invest in a DIB for a vaccination drive, because there is no additional benefit from focusing on outcomes (immunisation) versus the input activity itself (administering a vaccine). In contrast, a DIB that aims to improve learning outcomes might be a better use of funds and time, because there are multiple approaches (or inputs) that could result in better learning outcomes. For example, service providers could focus on training teachers, providing better school infrastructure, increasing community accountability, running remedial learning programmes or providing ed-tech based supplementary content. This is because concrete evidence on which of these approaches is most effective in improving learning outcomes, is lacking.

DIBs are hence better suited for interventions that offer an opportunity to innovate, especially when the evidence on solutions is absent or unclear.

Ideally, approaches that have room for innovation are the best candidates for DIBs. This is because DIBs have been designed to bring in a new category of funders—private sector investors looking for risk-adjusted returns—that we don’t see with traditional development funding approaches.

Having said that, given that these investors are interested in some financial return, entirely new or disruptive approaches will not work either, as the perceived risk may be too great. But an approach that has some history of success and also offers room for innovation, is often the sweet spot because it justifies the need for risk capital.

There are certain sectors that are better suited than others for an impact bond

An assessment of whether there is an enabling environment for a DIB must also include an evaluation of the specific sector itself—how mature is it, what are the major gaps, how developed is the value chain, and how much evidence exists on outcomes.

Whether there is an enabling environment for a DIB must also include an evaluation of the specific sector itself.

Globally, in the last year alone, 24 new impact bonds have been announced across social welfare, employment, healthcare, and education. Most of these have been in developed nations. Looking at the Indian development landscape, we believe that a few sectors are better ‘primed’ for an impact bond, than others.

The education sector has seen much interest in the impact bond market in India. The India Education Outcome Fund, established to mobilise impact bonds at scale, will be supporting interventions across the education and employment spectrum from early childhood to primary and secondary school, and school to workforce transition. Both sectors are viable for impact bonds because outcomes can be clearly measured, and there are many approaches with the potential to achieve them.

The health, sanitation, and waste management sectors are also well suited because they offer clearly defined, measurable outcomes.

For instance, in waste management, ‘reduction in the volume of waste going into the landfills’ and ‘an increase in the recycling of reusable materials’ can be achieved by both for-profit and nonprofit service providers.

In the fields of health and sanitation, there have been approximately 13 contracted impact bonds. These have primarily focused on preventive healthcare (hypertension in Canada, diabetes in Israel, maternal and new born health in the US), and reducing indirect costs of illness such as reduction in sick leave, and reintegration for cancer patients. In India too, Utkrisht was launched to reduce maternal and child mortality by ensuring private hospitals meet the government’s quality accreditation standards. Outcomes such as child mortality can also be achieved through other pathways, for instance by looking at allied sectors such as sanitation, where there are proven links to under-five mortality.

We have often seen that most business models in these sectors have typically not been able to unlock much equity funding. A number of factors–long gestation periods, low margins, difficult operations, and under-developed markets–enhance the risk perception and reduce the expected return on investment (RoI). DIBs thus offer an alternative model, through which the risk investor’s return is no longer linked to financial return attained by a service provider. Instead, it is tied to the level of social or environmental outcomes achieved.

We are still fairly early on in our journey using DIBs as a tool for achieving outcomes. Though we have learnings around which sectors and approaches might be better suited for impact bonds, and there seems to be an appetite among donors to participate, we are yet to get the Indian government involved as a partner in this journey. At the very least, DIBs will spark innovation and attract new kinds of capital to this space. And hopefully with time, the Indian government will become an outcome payer too.

- The difference between a Development Impact Bond (DIB) and Social Impact Bond (SIB) is based on the outcome funder. When the government is the outcome funder, the instrument is referred to as a SIB, alternatively, in a DIB, a private foundation is an outcome funder.

- Data as of 1st January by Brookings Institute: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Impact-Bonds-Snapshot-January-2019.pdf

_

Disclaimer: Vikram is a founding board member of Social Finance India, which houses the The India Education Outcome Fund and the India Impact Fund of Funds.

Aparna Dua and Riya Saxena from Asha Impact Trust contributed to this article.