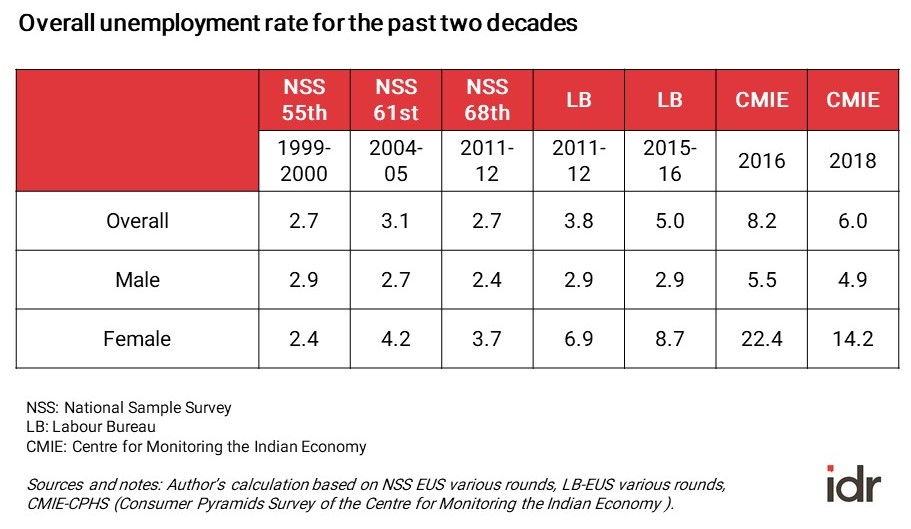

The 2019 State of Working India report by Azim Premji University (APU) states that five million men lost their jobs between 2016 and 2018; and that at six percent, the overall unemployment rate in 2018 has doubled from what it was in the decade between 2000 and 2011. Needless to say, the Indian economy is failing to provide adequate number of jobs for its people.

Who is affected?

Youth, especially those with higher education, comprise most of India’s unemployed, with a disproportionate percentage being represented by people in the age group of 20-24 years.

A fundamental reason for this is that this group can ‘afford’ the luxury of being unemployed. In other words, they choose to wait till they find a desirable, formal sector job, instead of taking up any available job in the public sector.

This could explain why between 2000 and 2011, while the overall unemployment rate was at three percent, the unemployment rate among the educated was 10 percent.

Between 2000 and 2011, while the overall unemployment rate was at three percent, the unemployment rate among the educated was 10 percent.

On the other hand, open unemployment is low for the less educated. But owing to uncertain and erratic work opportunities, there is a higher tendency in this group to be out of the labour force.

Women are the worst affected. Among the 10 percent graduate working urban women population, 34 percent are unemployed.

The report also presents data that highlights that workers in the informal sector have also been losing jobs since 2016.

Related article: The geography of employment in India

What are the reasons for the decline in employment?

While demonetisation is often blamed for the economic decline post 2016, as per the APU report, no direct causal relationship can be established here. But, there are several other demand and supply-side factors responsible for lower employment rates. A few are outlined below:

- High growth rates and aspirations, especially among the youth: The higher growth rates since the 2000s on account of India’s privatisation has led to the creation of a more aspirational middle class – one that is less accepting of petty informal work. Moreover, with a median age of 28, India is a country with large number of young people keen on doing highly rewarding jobs. The lack of such jobs results in them remaining unemployed.

- The education wave: Today’s youth have much higher levels of education. A 2015 Employment-Unemployment Survey by the Labour Bureau states that only 12 percent of the labour force in the country is without any formal education. In fact, in 2015, the enrolment rate for secondary education reached 90 percent. Additionally, the enrolment rate for higher education (18-23 age group) also rose to 26 percent in 2016 from 11 percent in 2011. This change in educational levels has led to the desire for better jobs–something that the economy is failing to offer.

- The dominance of ‘general’ degrees: While college enrolment has reached all-time highs, as per the All India Survey of Higher Education, out of the eight million students who graduate every year, only around one million receive professional degrees. This means that the remaining receive Science, Arts and Commerce, and other ‘general’ degrees, which often do not prepare graduates for jobs in the modern economy.

- Sub-standard degrees: The employability crisis deepens when even those with professional degrees like engineering or management are not ‘job-ready’. There is a big discrepancy between company requirements and the candidates’ skill set. According to a 2016 survey conducted by Aspiring Minds (based on 150,000 engineering students), only seven percent of them were equipped to take up core engineering jobs. Thus, companies without resources to train candidates avoid hiring them.

India’s privatisation has led to the creation of a more aspirational middle class – one that is less accepting of petty informal work | Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

- Caste: Caste has two major effects in this context: it creates powerful incentives on the part of lower castes to move away from their traditional caste-bound occupations. At the same time upper castes refrain from considering any occupations that have a manual component. This results in a huge supply of labour to white-collar and desk-oriented jobs ensuring that only those who do not have this option are left to work in other occupations and trades.

- Gender: Traditional gender norms helped keep unemployment numbers low because they prevented women from entering the labour market. They ensured that women’s work remained invisible because unpaid household work was not considered work. Now, with higher education levels among women, more of them want to join the labour force. But traditional gender norms are still firmly entrenched and limit their job choices and mobility. Male-dominated jobs networks also contribute to the alienation of women in the market. Because of this, women often end up in positions with low pay and less responsibility which dissuades them further from working, especially when family incomes rise.

- Collapse of public sector: The public sector has been a large and highly-coveted employer of general purpose graduates. However, the push to the neo-liberal agenda has led to the shrinking of the public sector; this has coincided with an increase in educated youth, thereby resulting in a bigger gap between jobs available and number of applicants, leading to increased unemployment.

- Automation and AI: Due to rapid advancement in automation, the ability of the manufacturing sector to generate jobs has quickly reduced. In addition, the processes of global integration have ensured that even developing, labour-intensive economies like India can to do little to avoid the adoption of labour-displacing and capital-intensive technologies. Consequently, automation and AI have a very high job-displacing potential.

Related article: Labour market effects of workfare programmes: Evidence from MGNREGA

What can be done?

The concern now is that the Indian economy will not be able to absorb surplus labour before there is a significant social dislocation. The APU report, therefore, discusses the need to implement several long-term and short-term measures involving large amounts of public spending to improve employment rates. These measures include:

The implementation of an employment guarantee programme like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in urban areas is one way to provide a legal right to employment. This urban employment guarantee scheme can ensure not just employment to those in need but also better infrastructure and services, restoration of ecology and urban commons, enhancement of youth skills and ultimately, an overall increase in human and financial capacity.

India has always under-invested in basic social services for its citizens. Increased public spending on Universal Basic Services (UBS) will have the dual benefit of supplying quality services and creating good jobs. Ensuring better provision of services like health, education, housing, securities, transport and utilities will result in everyone having a minimum quality of life regardless of their social or economic class.

Taking cues from the Chinese and East Asian models of development, India also needs to rethink its industrial policy by making it more government-led as opposed to market-led. It cannot fall into the trap of de-industrialisation as yet, and should support the manufacturing sector to generate more jobs for its young workers and promote entrepreneurs. For that, the state will have to resist the Washington-led neo-liberal consensus, and take a more active role in protecting its industries.

While economic growth has allowed India to bring down poverty rates dramatically, especially extreme poverty, growth has not translated into jobs. Given India’s burgeoning youth population, there is an urgent need to craft a government policy, adequately supported by budgetary resources, to promote employment generation. Ultimately, the best remedy to alleviate poverty is enough jobs and enough high-quality jobs.

The central government has enough fiscal space to adopt a robust employment generation policy. Even a doubling in the outlay on MGNREGA would hardly be extravagant. Moreover, the high potential multiplier of such outlays is likely to result in robust growth and tax revenues, thereby limiting the deficit.

*Lamya Karachiwala contributed to this article.