Indigenous Adivasi communities often bear the brunt of mainstream development models initiated by the state. Projects such as dam construction and the acquisition of land and forests for mining have disrupted their ways of life and traditional livelihoods. The Katkari, Thakkar, and Mahadeo Koli communities, which live in the Ambegaon block of Pune district in western Maharashtra, have also paid the price of development. But ours is a story of resistance, solidarity, and determination in the face of systemic challenges.

For generations, the Katkaris relied on fishing in the Ghod and Bubra rivers, while the Mahadeo Kolis cultivated rice, wheat, and vegetables on the surrounding land. I myself am a member of the Mahadeo Koli community. Both communities faced economic and social hardships due to the construction of the Dimbhe Dam in the Krishna Basin, a project initiated in 1972 and completed in 2000.

As the dam started to fill up, its backwaters flooded fertile lands. By 2000, when the gates of the dam were installed, 25 villages were either completely or partially displaced. Twelve of these villages were fully submerged, leaving hundreds of families without land or livelihood. By 2006, the Katkaris’ already limited fishing rights to the reservoir were monopolised by outside contractors, which further disenfranchised the community. Without a permanent home, income, or access to subsistence farming and fishing, many families were forced into seasonal labour such as brick-making—an occupation that trapped them in cycles of debt and servitude.

Our already precarious situation was made worse by an inefficient and inequitable resettlement process that denied displaced communities viable alternatives to land and livelihood. In many cases, for instance, only the eldest male member of a family was eligible to receive rehabilitation land, leading to disputes among siblings and the displacement of families.

Faced with these challenges, Adivasis from the Katkari, Thakkar, and Mahadeo Koli communities collectivised to fight for our rights. It has been a long and difficult struggle, but we pressed on and achieved inspiring victories along the way. In the process, we also garnered support from fishing, tribal, academic, and civil society circles outside our own district. Here’s how we did it.

1. Mobilising for collective action

In the past, the Katkari community used small nets to fish in the shallow waters of the Ghod and Bubra rivers. However, after the dam was built, the reservoir’s increased depth and vastness necessitated boats and large nets—equipment the fishers could not afford. There were other problems as well. As land parcels shrank, people living near the dam under the traditional joint family landholding system faced complications and uncertainty over land rights.

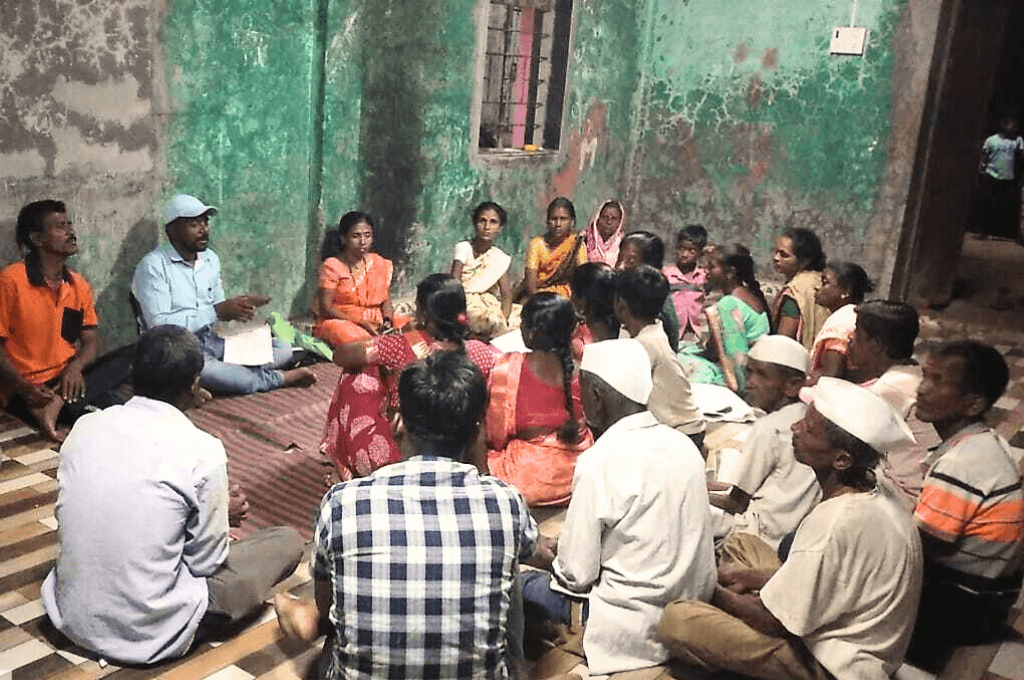

In 2006, people from 19 affected villages came together to demand fishing rights in the Dimbhe Dam reservoir. The process of collectivisation was not easy. Initially, it was difficult to meet with government officials and get them to listen to us, whether through protests or negotiation. But the being excluded from fishing opportunities increasingly deepened our marginalisation, forcing community members to form a cooperative society, the Dimbhe Jalashay Shramik Adivasi Macchimar Sahakari Society (DJSAMSS). Today, the cooperative includes more than 300 families across communities.

2. Leveraging stakeholders across the board

We invited the then divisional commissioner of Pune district, Prabhakar Karandikar, to inaugurate our cooperative’s board. A staunch supporter of our demands, he spearheaded the Dimbhe Dam Area Poverty Alleviation Programme. The programme aimed at restoring the fishers’ livelihoods through a partnership between government agencies, nonprofits, and research and academic institutions. It focused on the 38 villages that fall within the dam’s catchment area. Mr Karandikar played a key role in bringing together these stakeholders and aligning government schemes from the revenue, cooperative, tribal development, and fisheries departments.

Leveraging the support of a broad network such as this was one of our key strategies. Organisations such as Central Institute of Fisheries Education (CIFE), Mumbai, and Foundation for Ecological Security (FES) provided critical resources, including capacity building, training, research, and information. Meanwhile, the Rotary Club of Pune contributed boats and nets, enabling the community to transition from traditional river fishing to deep-reservoir fishing. Academic institutions like IIT Bombay offered technical assistance in implementing advanced fishing methods, such as cage culture.

Cage culture became a pivotal tool in the collective’s success. The method involves placing small fish inside a fine net that is fastened to a frame submerged in water. The fish are fed until they grow to a certain size and are then released into the reservoir at the end of the monsoon. The approach not only prevents fish from being washed away during the dam’s overflow but also protects them from predation by larger fish. This method has increased the population of Indian major carp species such as rohu, catla, and mrigal in the reservoir. With training from IIT Bombay and the Ministry of Tribal Development of Maharashtra, the Katkari community mastered cage culture techniques, turning the dam into a sustainable source of livelihood.

The adoption of cage culture also positioned DJSAMSS as a model for sustainable fisheries management. Fishers from Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, and Bihar now visit Dimbhe Dam for training workshops organised by the cooperative. This recognition has further strengthened the community’s standing and showcased the effectiveness of our collective action.

3. Advocating for rights, recognition, and policy changes

The formation of the DJSAMSS was just the beginning. Supported by other tribal communities in the region, the Katkaris continued to assert their fishing rights. While our efforts to establish a collective and adopt advanced fishing techniques were transformative, we expanded our campaign to other areas of livelihood rights.

a. Fighting for community forest rights

The expansion of the dam’s backwaters trapped some settlements between reserve forests on one side and water on the other. In Bhimashankar Sanctuary, for instance, the backwaters now encroach within 200 metres of the protected forest area, drastically reducing cultivable land available to farmers. At the same time, the forest’s protected status prevents them from farming and harvesting non-timber forest produce (NTFP), a practice they followed for generations.

When Bhimashankar Sanctuary was established in 1985, we supported forest conservation even though some farmers owned land within its boundaries. However, with farming restricted by the dam and NTFP harvesting denied by the forest department, there are few resources left to support us. We therefore demand community forest rights under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, for the sustainable use of forest land. Community stewardship of the forest would help prevent exploitation, promote conservation, and allow us to manage fire incidents and plant new trees. Since 2010, we have filed numerous community claims, but progress has been slow. Officials lack understanding and interest, while the forest department fears losing control to local communities, further delaying recognition of our rights.

b. Engaging in legal battles

From 2006 to 2014, DJSAMSS members fished in the Dimbhe Dam reservoir under a renewable five-year lease. The lease, initially set at INR 56,000 a year, was later raised to INR 1,21,000. The cooperative covered this cost through contributions made by more than 300 member families, selling their catch in Nashik, Pune, and Mumbai. However, from 2015 onwards, a policy change increased the lease to INR 7 lakh per year, making it financially unviable for the fishers.

To make matters worse, the government started selling fishing leases to private contractors from outside the region, permitting them to lease dams larger than 1,000 hectares.

We challenged this policy in the Bombay High Court in 2015, demanding open tender rights to fishing. Midway through proceedings, however, the government proposed that we withdraw the case in exchange for exclusive fishing rights. But we still had to pay the INR 7 lakh lease. Unable to pay the amount upfront, we negotiated an agreement to pay it annually in two instalments. Our legal battle thus secured exclusive fishing rights for our cooperative, protecting our livelihoods. However, this was a short-lived victory.

In 2024, the government increased the lease to a steep INR 24 lakh per year and opened the tender to outside bidding once more, pushing us back to square one. We have since been protesting this move for it has once again made it challenging for the cooperative to fish in the reservoir.

c. Working with government departments

DJSAMSS complemented its legal campaigns with policy advocacy. In 2015, the group engaged with the state’s Ministry of Tribal Development to secure INR 1 crore to expand fisheries operations to other dams in the region, including Chaskaman Dam in Khed taluka and Manikdoh Dam in Junnar. This financial support enabled the cooperative to provide training, distribute equipment, and enhance the fishing practices of tribal communities, creating a ripple effect across multiple villages.

The building blocks of our movement

As the original inhabitants of the land submerged by the dam, we have a rightful claim to its resources—this is the simple premise of our protests. And while this objective hasn’t been realised yet, what we have succeeded in doing is building a people’s movement that goes beyond Dimbhe Dam and the Krishna Basin. Here are some of the factors that have helped build this movement:

- Unity and representation: Adivasi lands are unique, and our demands centre on community rights rather than individual rights. We believe that entrusting communities with forest and fishing rights ensures environmental balance and long-term conservation—a cause that many communities ended up supporting. The collective’s inclusive approach brought together multiple Adivasi communities, including Katkari, Mahadeo Koli, and Thakkar, as well as Muslim families in the region. This unity strengthened our bargaining power and ensured broader representation.

- Strategic campaigning: DJSAMSS’s strategy of combining legal action, policy advocacy, and grassroots mobilisation addressed challenges at multiple levels. Additionally, by collaborating with nonprofits, academic institutions, and government agencies, we gained access to resources and expertise that were otherwise unavailable to the collective. This comprehensive approach ensured that we were able to overcome technical and financial barriers and that our demands were heard and acted upon.

- Use of current, sustainable technology: The adoption of cage culture and other sustainable practices not only improved livelihoods but also demonstrated the long-term viability of our initiatives. Moreover, we have long protected our lands, forests, and water bodies, safeguarding these areas from mass, unsustainable consumerism and extraction. This focus on sustainability garnered support from both governmental and non-governmental stakeholders.

- Resilience: Despite the challenges posed by the dam and initial resistance from government officials, the community’s unwavering determination kept the movement alive for decades. Organising a collective like DJSAMSS gave our struggle structure and voice. The Katkaris and other communities also demonstrated resilience by adapting to new circumstances, such as transitioning from river to reservoir fishing.

The journey of DJSAMSS underscores the importance of collective action in addressing systemic injustices. It is a reminder that even in the face of oppression, displacement, and marginalisation in the name of development, Adivasi and rural communities have forged a path forward.

—

Know more

- Read this report to know more about the technique of cage culture in fishing.

- Read this article about development-induced dispossession for Adivasi communities.

- Read this interview with Madhu Mansuri Hasmukh, a renowned Adivasi rights activist known for his role in the Jharkhand movement.