In December 2024, the Union Government amended the Right to Education (RTE) Act of 2009, allowing schools to detain students in classes 5 and 8 if they do not meet progression standards. This change follows years of inconsistent implementation of the RTE’s No Detention Policy across states and grade levels. Reports from the Central Advisory Board of Education Sub-Committee for Assessment and Implementation of Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation indicate that Goa, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Sikkim may have previously detained students after class 5—despite national guidelines recommending no detention up to class 8.

There are a range of factors that could be associated with a child being held back in a grade. Some of these are easily captured in data related to household factors (for example, education level of the parents) and socio-economic status (for instance, a child’s family does not have sufficient resources to invest in education to help them progress), but others are harder to measure. For example, prior work by economists suggests that teacher characteristics play an important role in whether a child is held back—if a teacher is biased towards boys or girls, they may systematically hold back an entire group of students despite having little academic basis to do so.

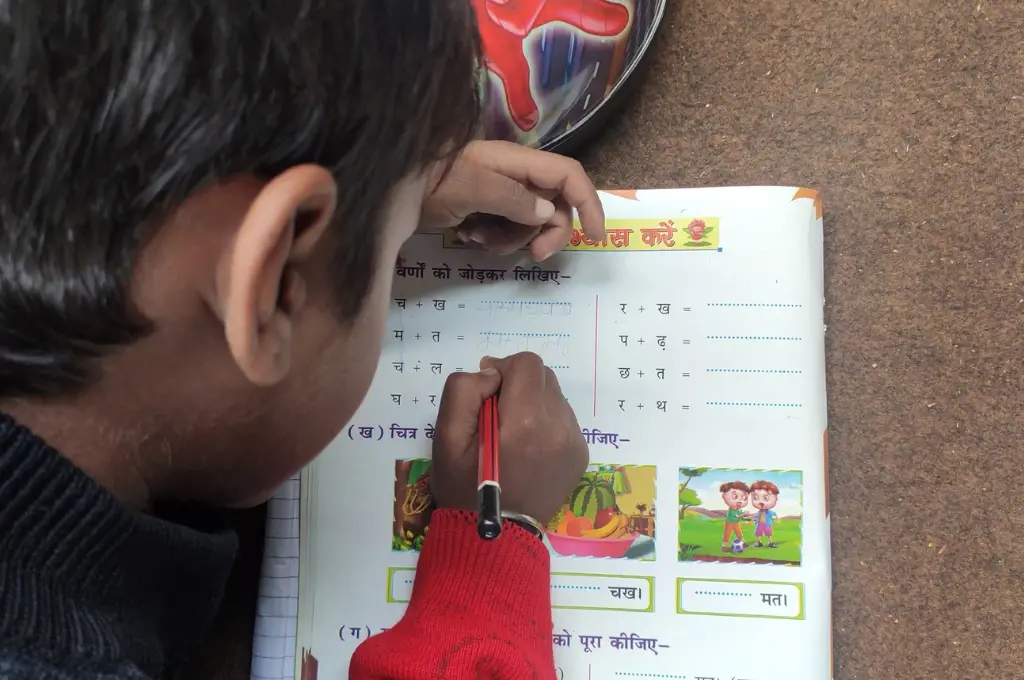

However, research has not yet focused on another important factor in multicultural and multilinguistic societies that relates to the medium of instruction at school. The link between the medium of instruction at school and whether a child is held back is not straightforward—in many studies, children who attend English-medium schools show marked improvements in school outcomes despite English not being a language they speak at home. At the same time, learning in the same language as the one spoken at home could confer what linguists and sociologists call ‘language capital’, that is, advantages in terms of knowledge and skill acquisition since the child already has command over the language in which they are being taught.

In a recent paper that I co-authored with Bijoyetri Samaddar and published in Education Economics, we examined grade repetition among children who speak a different language at home than the one used at school. We compared these children with those whose home and school languages are the same. To do this, we used child-level data on whether students were repeating a grade, along with household and school-related inputs.

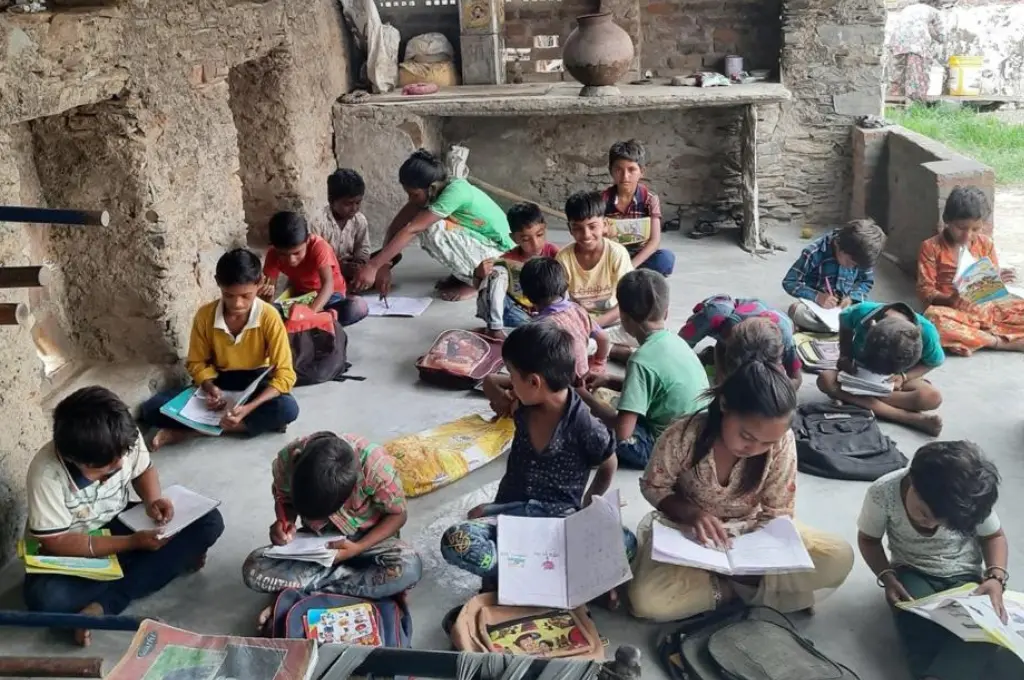

The household-level factors that we examined included spending on education—such as fees and private tuitions—and parental education levels. For example, a systematic review found that in low- and middle-income countries, private tuitions can influence how language affects children’s literacy development. At the school level, key inputs included scholarships, classroom infrastructure, and teacher quality. Beyond infrastructure, studies from India and other low- and middle-income countries show that provisions like mid-day meals (between 1998 and 2005) have positively impacted attendance and other child outcomes.

We used data from the 75th Round of the National Sample Survey (NSS), which was conducted between July 2017 and June 2018—prior to the introduction of the National Education Policy (NEP). This round covered more than 1,00,000 children across India. Using statistical models, we examined the factors associated with grade repetition. Below are some of the key findings:

1. Native language instruction is not clearly linked to schooling advantages

Overall, the incidence of grade repetition was low—only 3.2 percent of children in the sample reported being held back, with no significant difference between boys and girls currently attending school. However, this varied depending on the type of school attended and whether there was a mismatch between the child’s home language and the language of instruction at school. This finding suggests that policies promoting instruction in the mother tongue may have different implications for children from diverse linguistic backgrounds.

In the overall sample, there are negligible differences between genders with respect to grade repetition when there is a language discrepancy. However, children who repeat a grade and do not study in the same language as the one spoken at home tend to differ systematically on other factors—most notably, education-related spending.

2. Language mismatch and grade repetition are linked to household education expenditures

Among households where children face this language mismatch and are held back, expenditure on course fees is approximately eight times higher than the sample average. This suggests that a large part of the difference in education-related spending could be on account of more expensive schooling.

In our sample, the average reported difference in fees between private English-medium and private non-English-medium schools is close to INR 15,000. Given the higher average course fee among children experiencing a language mismatch and that only approximately 0.2 percent of households report English as their home language, we can infer that a language discrepancy is likely to be especially common among children attending English-medium schools.

3. Impact of language mismatch is different across groups

Finally, our results show that language differences between home and school do not always lead to grade repetition. Among boys from urban, wealthier households, this mismatch appears to reduce the likelihood of repeating a grade. This may be due to the potential for these households to invest in private tutoring, helping to compensate for the challenges associated with a language mismatch faced by the child.

However, for girls studying in non-English-medium schools and those in non-Hindi-speaking states, language discrepancy increases the risk of grade repetition. This finding highlights that the impact of a language mismatch varies across demographic and linguistic groups.

Implications for policy

A key takeaway from these findings is that a specific subgroup of children is more likely to be affected by sweeping changes to the medium of instruction in Indian schools. The NEP, which advocates for using children’s mother tongue or a local language as the medium of instruction, has not yet been fully implemented across states. Non-Hindi-speaking states should therefore carefully consider how such a change in the medium of instruction may impact girls in particular. For example, the study found that in non-Hindi-speaking states such as Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, girls studying in non-English-medium schools face an increased risk of grade repetition when their home language differs from the language of instruction—highlighting a pronounced gendered effect of language mismatch in these contexts.

Another implication concerns the children of migrants in both urban and rural areas. Students from families that have migrated to another state may lack the home language advantage that native speakers enjoy when instruction is delivered in the regional language. While our dataset, drawn from a nationally representative survey, covers diverse regions, it does not provide specific statistics on the proportion of interstate migrant households within the sample, limiting our ability to assess their specific representation. Future research should consider studying English-medium schools, particularly where English is spoken at home—even if not as a native language. More data from the NSS or other sources is needed to better understand the link between language discrepancy and grade repetition in these settings, especially as English-medium schooling increasingly signals social status for parents, and is often associated with wealthier households and aspirations for upward social mobility.

Our findings suggest a complex interplay of factors through which language discrepancy can influence educational outcomes. As states begin to adopt the NEP, recent changes to the No Detention Policy will need to be studied closely to understand how they may affect boys and girls differently across regions. Ongoing monitoring of these changes will be crucial for identifying their varied impacts and informing future policy.

—

Know more

- Read the study that this article is based on.

- Read this article on the need for amending the RTE Act to effectively implement the NEP.

- Learn more about centring indigenous languages under the NEP.