During a recent classroom activity at a government school in Odisha’s Dongria Kondh area, students were asked to write down what they want to be when they grow up. The answers—engineer, doctor, teacher, police officer, IAS officer—were similar. A few mentioned unconventional roles such as influencer and dancer. Some simply wrote, ‘No idea.’ But even for those who have made a career choice, would they also have figured out a career path?

According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2023, technological shifts are dramatically reshaping the global labour market. Roles in data science, AI, renewable energy, and healthcare are growing, while traditional administrative jobs are declining. India’s next generation must prepare for jobs that barely existed a decade ago.

Yet youngsters are navigating their futures without much of a road map. In a 2022 study conducted by Quest Alliance with 1,500 secondary-school learners across the Mysuru and Tumkur districts in Karnataka, 65 percent of boys and 39 percent of girls reported having social media accounts—highlighting the potential influence of social media on young people’s aspirations—and 88 percent said they use the internet to seek information on careers.

However, structured, contextual career exploration that connects aspirations to the world of work and real opportunities in the future, which is essential to set students on the path of career planning early on, is missing in schools.

What influences the aspirations of young people?

For many, formal education is the gateway to a better life, but access to meaningful career guidance is missing.

Gender norms dictate ‘appropriate’ professions—girls are discouraged from pursuing STEM, and boys hesitate to take up caregiving roles.

Most aspirations are still around a handful of professions—doctor, engineer, police officer, teacher, and government employee. These roles are viewed as secure, respectable, and financially rewarding. New-age aspirations might be emerging due to rising use of social media, but these choices often come without clarity about pathways or evolving jobs.

The landscape of career decision-making is fraught with deeply ingrained biases. Gender norms dictate ‘appropriate’ professions—girls are discouraged from pursuing STEM, and boys hesitate to take up caregiving roles. A girl expressing interest in being a cab driver, or a boy wanting to be a nurse, can invite ridicule from peers, teachers, or family. These stereotypes are further reinforced by the intersection of economic barriers and gender. For instance, the higher cost of STEM courses after class 10 can dissuade girls from continuing in these fields, compounding the limitations imposed by societal expectations.

Many students are already working or supporting their families, some anticipating migration for better opportunities. For them, career decisions are often about survival, not self-fulfilment.

The need for effective career counselling

The Bharat Career Aspirations Report 2024 reveals that adolescents, especially in rural India, feel a lack of autonomy. After participating in a career decision-making exercise, a 16-year-old boy from rural Uttar Pradesh remarked, “I don’t know how to make decisions. I’ve never been allowed to.” Against this backdrop, the need for structured, equitable, and early career guidance is undeniable.

Career decisions unfold over a lifetime but for many students, especially around class 10, it can feel like a once-in-a-lifetime choice, with the need to choose a fixed path. However, in today’s world, people switch careers multiple times, and the requirement for different skills evolves rapidly. As OECD’s 2021 report on effective career guidance states: “Effective guidance is as much about personal reflection as it is about information.” What young people need is not certainty, but the confidence to navigate change.

It is imperative to go beyond job lists and develop a mindset that speaks to the changing world where people experience more than one career in a lifetime, skill requirements are rapidly changing, and technology is making some careers obsolete or altering them completely.

One way to achieve this is through digital tools.

Digital tools can help navigate career counselling

In the evolving landscape of career guidance, a range of digital tools and collaborative initiatives can empower young learners to navigate their futures with confidence. Tech-enabled tools offer students a sense of independence, and a safe space to express, experiment, or even critique choices without the fear of being judged, questioned, or corrected. This is especially helpful in schools that lack counsellors.

At Quest Alliance, we have supported the career journeys of youth in industrial training institutes (ITIs) and vocational training institutes (VTIs), and worked with school students to build self-awareness and gender sensitivity and facilitate career exploration.

One of our key interventions is Career Quest—a free browser-based game rooted in a cyclical journey of self-awareness, awareness of the world of work, and making a career plan. The game simulates real-life career journeys through different characters and storytelling techniques. It focuses not just on information, but also on the many factors that influence career decision-making, life circumstances, gender, beliefs, aspirations, and biases. For instance, Asmita, a transgender character, brings forth dilemmas of identity and acceptance, allowing learners to step into the shoes of someone whose struggles are often invisibilised. The challenges and gender biases Asmita endures during the game help learners understand how identities, such as caste, gender, and class, impact career decisions.

Tech-enabled tools give students the freedom to explore and question choices without fear of judgment.

The app also provides access to a wider range of career pathways and showcases real-life stories of diverse role models in engaging digital formats, which an educator or career counsellor cannot offer. The experiences that the gamified characters go through in the digital format can be far richer than the traditional career guidance provided by a teacher.

Unlike most conventional guidance models that focus on the top five to seven career paths—such as engineering, medicine, or government services—the game introduces learners to a broad spectrum of options, including those rooted in hobbies and personal interests. For instance, characters who enjoy cooking are shown pathways to careers as chefs or food entrepreneurs. Those with a passion for dance can explore the field of choreography. A character interested in sports is not limited to becoming an athlete; they can also be a sports journalist, statistician, physiotherapist, PE teacher, or even a sports photographer.

The goal is not merely to provide information but also to develop new ways of thinking about careers. Learners discover how a passion for storytelling might lead to a career in journalism, law, or filmmaking; how an interest in science can evolve into roles in AgriTech, ecology, or academic research. Other careers surfaced through the game include that of a nutritionist, manager at a fast-food chain, microfinance professional, IAS/IPS officer, lawyer, programmer, environmentalist, and professionals in the entertainment, fashion, and cosmetic industries.

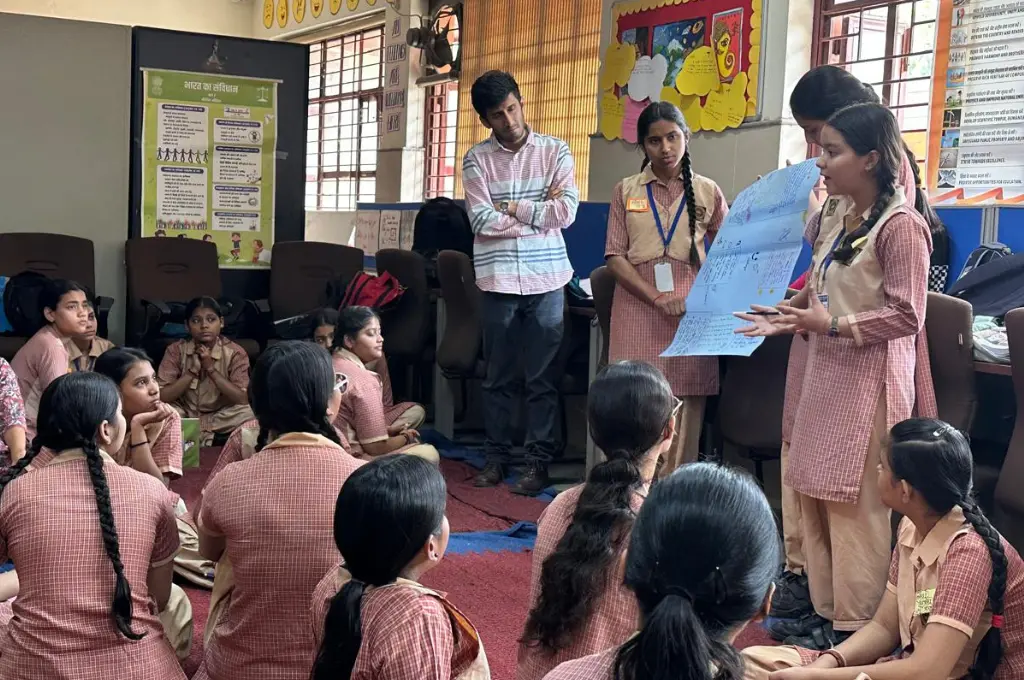

The game was born out of our extensive classroom experience with students and their responses to career conversations. What stood out during the game was a growing sense of autonomy among learners and how they engaged with the stories. Importantly, the game addressed the societal pressures that often lead students to pursue careers deemed ‘respectable’ or ‘safe’ by their communities, and encouraged them to explore paths aligned with their personal interests and strengths.

There are similar examples across the development sector. iDreamCareer offers a large-scale career guidance platform for students and educators. Antarang Foundation runs a chatbot to improve career literacy and readiness. UNICEF YuWaah supports portals and structured workshops, which are now being scaled across states.

However, these efforts must align with schools as well as with government machinery for scale and sustainability.

Tackling the scale challenge

1. Working with the government

The government has built large-scale digital education infrastructure through platforms like DIKSHA. A similar initiative is now needed for career exploration—one that combines information and assessments, guided activities for teachers, mentoring opportunities, and contextualised content for different learner realities.

Additionally, content co-creation and dissemination is another pathway through which governments and nonprofits can collaborate for scale. Often, engagement is prioritised in select schools, such as PM SHRI schools or model schools under various schemes, where there is an existing mandate for enhanced student development. These schools can serve as demonstration sites or innovation hubs for future scaling.

Nonprofits can collaborate with governments to enable this by co-creating national curriculums and implementation initiatives that focus on career exploration and decision-making, supporting structural changes and human resource allocation within the public education system. Nonprofits can be technical partners that contribute to position papers and policy on career readiness.

Beyond MoUs, structured coordination frameworks should define measurable goals: How do partners and the government align on capacity-building programmes and calendars for teachers and school leaders? How do nonprofits complement curriculum development? What mechanisms ensure continuity of implementing and improving career readiness curriculums in schools? Without such clarity, career guidance risks remaining piecemeal rather than systemic.

2. Integrating career guidance into school processes

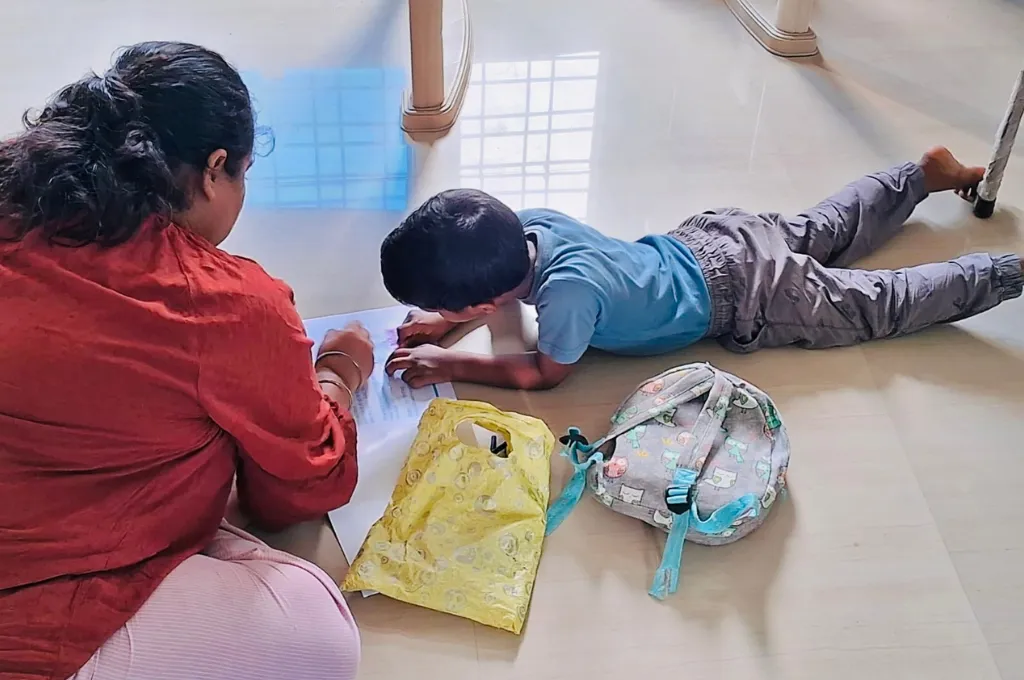

School education is where knowledge and work intersections can be best integrated. But to do this, the system must create space in the curriculum and academic calendars so that teachers are supported to nurture career guidance initiatives within the timetable. Extracurricular activities that allow students to explore their interests and uncover their strengths must also be valued. Unstructured, hands-on activities that let students discover their interests through play should be encouraged, as they foster creativity, intrinsic motivation, and a deeper understanding of one’s talents—laying the foundation for more meaningful and self-directed career choices.

Additionally, effective implementation requires a clear operational strategy, including deployment of career counsellors at a school cluster level; systematic teacher training to facilitate career discussions; integration of digital career resources into school curriculums; and regular industry engagement to expose students to real-world opportunities.

3. Understanding the importance of collaboration between civil society organisations

Several tools and programmes by civil society organisations have made their way into schools and at times directly to the youth, but within their own boundaries. There is a need for civil society organisations to come together to align on shared goals and not duplicate efforts.

Partnerships can accelerate adoption in government schools, making career guidance a systemwide priority. Rather than individual efforts operating in isolation, building an integrated, multi-stakeholder approach is key. Some organisations specialise in learning design, while others have strong policy advocacy or local implementation networks; leveraging each other’s strengths would maximise impact. While ideological differences may exist, a shared vision for equitable career guidance should drive collaboration forward.

4. Including parents in the career planning process

The Bharat Career Aspirations Report 2024, which surveyed adolescents aged 13 to 19, revealed that 33 percent of learners identified parents or guardians as their primary influencers in career decision-making. Many parents often reinforce traditional beliefs around gendered jobs and the notion that careers follow a fixed, linear path. This can curtail students’ freedom to explore, take risks, and experiment with career pathways that match their skill and interest.

To bring about a shift in mindset, parents should be included in the career counselling process to support their child through career transitions. This means engaging them in conversations, building their awareness of the evolving world of work, and equipping them to guide their children without imposing their own ideas.

A career guidance digital ecosystem could serve as an integrated space where young learners can explore career pathways through interactive guidance tools; access real-time labour market insights and job trends linked to the future of work; connect with mentors across industries to make informed decisions; find scholarships and funding opportunities tailored to their aspirations; and engage in internships and vocational training to bridge the gap between education and employment.

Even as we acknowledge the benefits of digital tools, there is a pressing need for more research and evidence on their effectiveness. Do they influence long-term decisions? How inclusive are they, especially in areas with limited digital access? In addition, beyond digital tools, real-world exposure is critical in bridging the gap between aspiration and informed career choice.

—