In the first article in this two-part series, we looked at the findings on discrimination in India’s labour market detailed in Oxfam’s India Discrimination Report 2022.

While that article detailed the extent of discrimination faced by Muslims, Women and members of the SC/ST community under ‘normal’ circumstances, this part focuses on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the extent of discrimination these communities face.

When the coronavirus pandemic touched down in India in March 2020, the subsequent nationwide lockdown had a devastating impact on employment. The unemployment rate in the country went from 6.8% in Jan-March, 2020 (henceforth referred to as the pre-pandemic quarter; PPQ) to 12.1% in April-June (first pandemic quarter; FPQ).

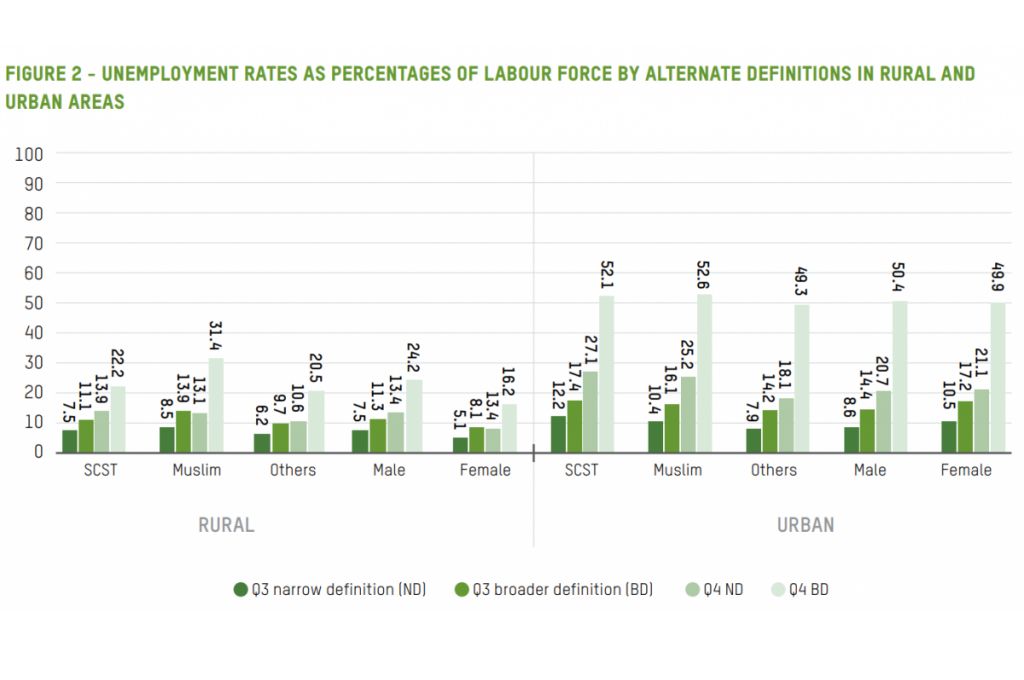

The impact was more severe in urban areas than in rural ones since lockdown measures hit urban businesses more severely. Unemployment in urban areas rose from 9% in the PPQ to 20.8% in the FPQ. However, urban areas saw a more-or-less consistent increase in unemployment across social groups; in rural areas, marginalised groups bore the brunt of the unemployment.

It should be noted that the figures mentioned above refer to employment as defined in the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS); as those seeking and available for work. This definition may not paint the most accurate picture since there were some individuals in regular and self-employment who were not included under this definition, despite reporting no work or income.

When the definition of employment is expanded to include those who reported no work during the reference week of the study, there is an alarming increase in the unemployment rate—rural unemployment under the broader definition went from 10.5% pre-pandemic to 22.2% in the FPQ and urban went from 15% to 50.3%.

Overall impact greater in urban areas; social discrimination greater in rural

Taking the broader definition of unemployment, one notices that the sharpest rise in the percentage of unemployed was for Muslims in rural areas (from 14% to 31%), whereas it rose from 11% to 22% for SC/STs in rural areas, and from 10% to 20% in the case of the general category.

The Report explains this as owing to the increased importance caste and religious identities assume in rural areas, particularly in times of crisis. People tend to function more and more within their own social groups.

Since both SC/STs and Muslims are socio-economically vulnerable, it stands to reason that the protection they can give and seek would be poorer and thus, they would feel the effects of discrimination more severely in rural areas.

Therefore, as mentioned above, while the overall impact of the pandemic in terms of unemployment was worse in urban areas, social discrimination was less because professional identities seem to supercede social ones there.

When categories of employment are considered, casual employment suffered the most, particularly in urban areas, because of the closure of non-agricultural activities. There was also a corresponding increase in self-employment, suggesting that it was taken up by casual workers as a means of survival. The largest number of workers that went from casual work to being self-employed was from the SC/ST community and according to the report, were largely employed selling essential goods during the lockdown.

Interestingly, only a small number of Muslims switched from casual work to self-employment with the onset of the pandemic, perhaps because Muslims are less likely to be socially accepted to deal with individuals in a household scenario. Muslims, instead, moved from casual work to unpaid family labour or unemployment.

In fact, the share of Muslims, as well as SC/ST workers employed in regular/salaried work, went up in both rural and urban areas, which likely has a statistical explanation—their total share in the workforce went down.

Employment among regular/salaried workers remained more or less the same or registered a marginal decrease, perhaps because the regularity of contracts meant there was no fall in the salaried workforce, or perhaps because the total workforce shrunk.

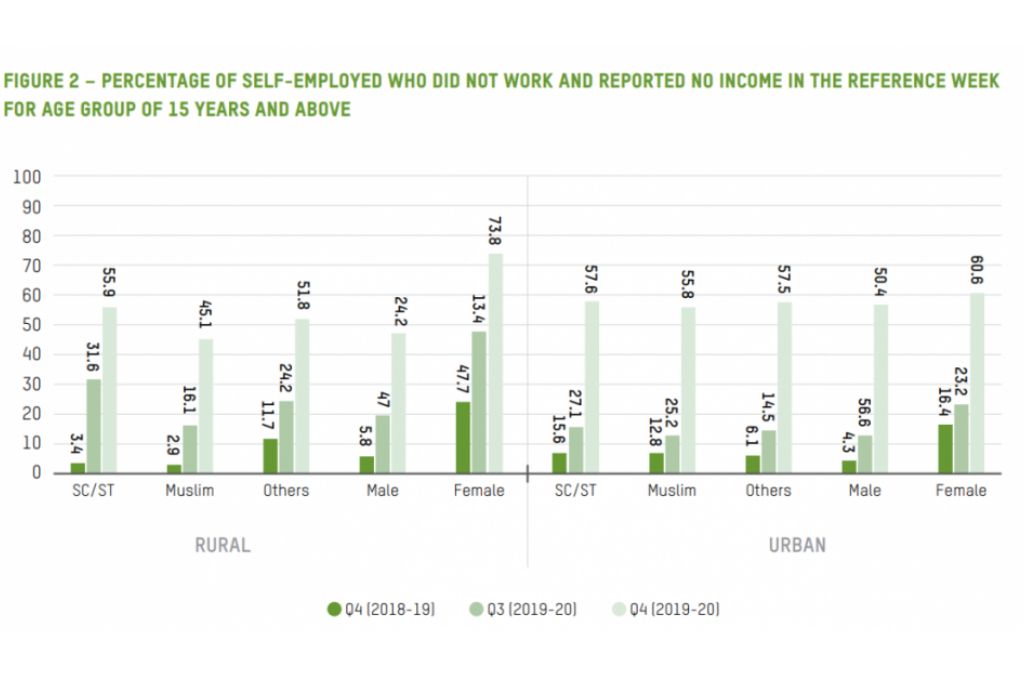

As suggested earlier, the highest ‘hidden unemployment’ was seen for the self-employed category since many casual workers were absorbed into it without having enough opportunities to work.

While 4.3% of self-employed people in rural areas reported not working in the PPQ, this number went up to 11.3% in the reference week of the FPQ. In urban areas, the share went from 7.5% to 39.8%.

Mixed findings on gender discrimination but women still worse off

As observed earlier, inequalities among groups vis-a-vis employment were relatively small in urban areas and this is the case for inequalities between genders too. The impact of the pandemic on unemployment figures were similar for men and women in urban areas, by both the PLFS and the expanded definitions of unemployment.

Women in urban areas, however, saw no increase in self-employment with the fall in the share of casual employment from PPQ to FPQ. While this was observed to a small extent in rural areas, even here, this trend was greater in men.

In rural areas, women recorded a lower drop in employment in the FPQ. This is likely because a large share of women in the rural workforce is employed in agriculture and household activities, both of which suffered relatively less disruption with the onset of the national lockdown.

When it comes to self-employed people who reported no work in the reference week of the pandemic, the share was higher for men than for women, as was the increase in this share from PPQ to FPQ. This follows from the previous point; that more men were absorbed into self-employment.

However, when it comes to regular employment, more women reported having no work in the reference week than men. While these results paint a mixed picture about the extent of gender discrimination during the pandemic, the Report notes, by and large, that individual indicators were more unfavourable to women.

Regular employment naturally affords more protections to employees. For instance, self-employed women who reported earning no money in the reference week went from 48% PPQ to 74% FPQ in rural areas and from 23% to 61% in urban areas. When the same figure is calculated for regular employment, however, it is found to be much lower because the legal system prevents employers from non-payment of salaries.

In fact, in rural areas among regular workers, this figure was higher for men—in the FPQ, 24% men in rural areas didn’t receive salaries while it was 14% for women. In urban areas, these figures stood at 29% and 22% respectively.

Impact of the pandemic on wages

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic saw a decrease in wages earned across the board in the FPQ—for all social identities and for all kinds of employment. What’s more, both rural and urban areas saw similar patterns.

Caste and religion perspective

In rural areas, overall average wages in the FPQ were 9% lower than average earnings for the preceding year (2019-20). The greatest decrease was recorded for Muslims, who saw a 13% decline in wages from pre-pandemic levels.

Interestingly, SC/STs saw the smallest decrease in average wages in the FPQ (10%), even lower than the general category, which saw an 11% decrease. This is because a large section of the SC/ST individuals is employed in essential services which, by their very nature, cannot afford to be disrupted and are low paying in any case.

While self-employed Muslims saw an 18% fall in average monthly wages, the same for regular employment was greater at 24%. These figures for SC/ST communities stood at 10% for both self-employed and regular employment categories.

The fall in the earnings of Muslims confirms that their increase in the share of employment was not a result of improvements in their conditions in the labour market; rather, it was a statistical occurrence due to the fall in the size of the total workforce.

Corresponding with the increase in unemployment (40%), average wages were the worst hit for self-employed persons, falling by one-third for all social groups. Conversely, the fall was lowest in regular work due to compliance with labour laws.

Casual work is the only category of work where Muslims and others didn’t see a significant fall in earnings. Despite the number of casual workers falling sharply from PPQ to FPQ, the wages for those employed in casual work did not suffer significantly.

The gender angle

In rural areas, women did not see a significant decline in their wages. In fact, women in regular and casual work actually saw a 2% increase in their wages while men saw a modest decline.

In urban areas, however, the wages of both men and women saw a steep decline in the FPQ. Self-employed men saw earnings decline by 36% from PPQ to FPQ while the same figure for women was 26%.

This figure was negligible for regular workers due to labour laws, as mentioned earlier as well, and for casual workers, both men and women saw a 10% decline in earnings.

While women suffered employment losses in urban areas because of the impact the lockdown had on their mobility and other factors, their earnings losses were mitigated to some extent because women in urban areas were often employed as domestic help and played an important role during the pandemic.

Gender discrimination in India’s labour market is structural. As noted in the previous article in this series, men earn considerably more than women on average in normal circumstances. What is interesting, however, is that these earning ratios saw no real change with the onset of the pandemic—the inequalities between the genders in terms of earnings are large, but they were large in normal circumstances as well and the pandemic did not do much to worsen it.

Recommended interventions

The Oxfam India Discrimination Report 2022 recommends a number of interventions to bridge the gaps in labour market outcomes between social groups, unearthed and quantified by the study; both particular to the pandemic as well as in ‘normal’ circumstances, as discussed in the previous article.

Women emerged as the ‘biggest losers’ when it comes to the extent of discrimination—they had fewer employment opportunities and earned far less than men, so much so that the added caste- and religion-based differences were relatively small among women.

What must be remembered, however, is that discrimination against women in the labour market as measured in the Report is not solely discrimination from employers but a sum total of discrimination they face through historical factors, gender roles and expectations, and household and other responsibilities.

As such, the Report recommends active incentivisation of women’s participation in the workforce, enforced through enhancements in pay, reservation in jobs, upskilling programmes and so on.

Further, measures should be instituted to mitigate the factors of womanhood that employers see as reducing the strength of their endowments, for example, maternity. Women should be provided with easy return-to-work options after motherhood or be allowed to work from home, wherever possible.

Another step in this direction would be to strengthen the engagement of civil society in ensuring a more equitable distribution of parental responsibilities between men and women.

As for SC/ST identities, the Report showed how a greater extent of discrimination was found due to the improvements in endowments brought about through affirmative action programmes. Such a focus on building capabilities across groups, in terms of education and health, particularly for poor and vulnerable groups, is imperative.

Finally, the relatively low levels of discrimination in regular work, enforced through labour laws, need to be brought into the other categories of employment as well. Working to formalise contractual labour and casual work, enforcing “living wages” instead of minimum wages for unorganised sector employees and so on will work to reduce the prevalence of discrimination across India’s labour force.

This article was originally published on The Wire.