Over the past few years, there has been a renewed focus on early childhood education (ECE) in India, with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 serving as a major impetus. The policy places particular emphasis on ECE, which focuses on children between the ages of three and six years, and links it to formal schooling. While the right to education has not yet been extended to children under the age of six, the NEP aims to universalise ECE by 2030.

At present, the ECE system is spread across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, ranging from private preschools to government-run rural Anganwadis—resulting in significant gaps in the kind of learning provided to children. In this otherwise fragmented landscape, Vipla Foundation has been working on early interventions in Balwadis (preschool centres) in Mumbai for more than three decades. The organisation has since integrated technology into its Community Balwadi initiative in order to observe children’s progress and offer mentorship and training support to teachers.

Vipla directly runs 47 community Balwadis. With 25–30 students across different age groups in each classroom, these centres are located in informal settlements and serve children who are unable to reach the preschools under the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC).

In 2020, the Umang STCI Teacher app was introduced in community Balwadis to record attendance, track the number of days a centre is open, document classroom activities, assess each child’s development using evaluation tools. Teachers are supported by mentors, who monitor classrooms daily through both in-person visits and the data uploaded to Umang. Between 2022 and 2023, in collaboration with the BMC, the app was rolled out across 900 Balwadis in municipal schools.

To understand how leveraging technology can strengthen early education interventions, we spoke to Vipla about their experience with Umang over the past three years.

Building accessible technology

1. Tech adoption through hands-on support

The first step was to train Balwadi teachers—women from the local community—to download and use the app. This is a process that began with learning how to use a smartphone and overcoming the hesitation to engage with technology. There were also immediate challenges. Some teachers did not own smartphones, while many found it difficult to input children’s enrolment details. Moreover, the bulk of the data that teachers log into the app is entered in real-time at the Balwadi. Initially, they also had to do dual data entry—first in a register and then on Umang.

However, with time and hands-on support, teachers began to see value in the insights that emerged from the data they had tracked. For Vipla, this shift was made possible largely through continuous classroom support, peer learning, and training offered by a mentor team, along with practical, user-friendly features such as drop-down menus and offline access for data entry.

2. Tracking attendance to address absenteeism

“There are a lot of activities conducted in a Balwadi on a day-to-day basis, and if a child is regularly missing out, it is going to have some impact on their learning,” says Swapnali Thakurdesai, a programme manager at Vipla.

Therefore, the first feature provided by the Umang app is attendance tracking, which used to be recorded in registers. Tracking it through the app generates the average attendance in the classroom at the end of each month.

Swapnali explains, “Now, teachers and mentors can easily identify which children are not coming to the Balwadi regularly and flag any concerns. Teachers are also taking the initiative to reach out to parents and understand the reasons behind a child’s absence. If necessary, both teachers and mentors conduct home visits to meet with families.”

Based on a survey conducted by teachers, the causes of absenteeism include not only broader social and environmental factors—such as health concerns arising due to poor hygiene and sanitation conditions, or migration to native villages for four to five months each year—but also a lack of information and awareness about the significance of early childhood education.

“Over the past two years, we have been working to strengthen parents’ involvement, and we have seen a shift,” Swapnali adds. “Sometimes, parents might assume that since the child is young, missing a day or even a few days at the Balwadi might not impact their learning. If a child is absent, a teacher will first try to reach out to the parents directly. But if the parents are not responsive or if absenteeism becomes a pattern, then both teachers and mentors conduct home visits to address the issue with parents.”

Meanwhile, in Balwadis under the BMC, where child absences exceeding 18 days must be formally noted, Umang has helped teachers identify children who have been not attended the centre for more than 12 to 15 days. The app is also used to track enrolment and dropout rates, as well as the number of children who have transitioned to formal K-12 schooling.

Creating a feedback loop based on classroom evaluations

According to Vipla’s CEO, Pramod Nigudkar, the app was designed with the intention of documenting what is happening in a classroom on a single dashboard and combine this with teacher insights and mentorship. “It uses technology to identify and support children, rather than just measure them,” he adds.

1. Tracking each child’s progress

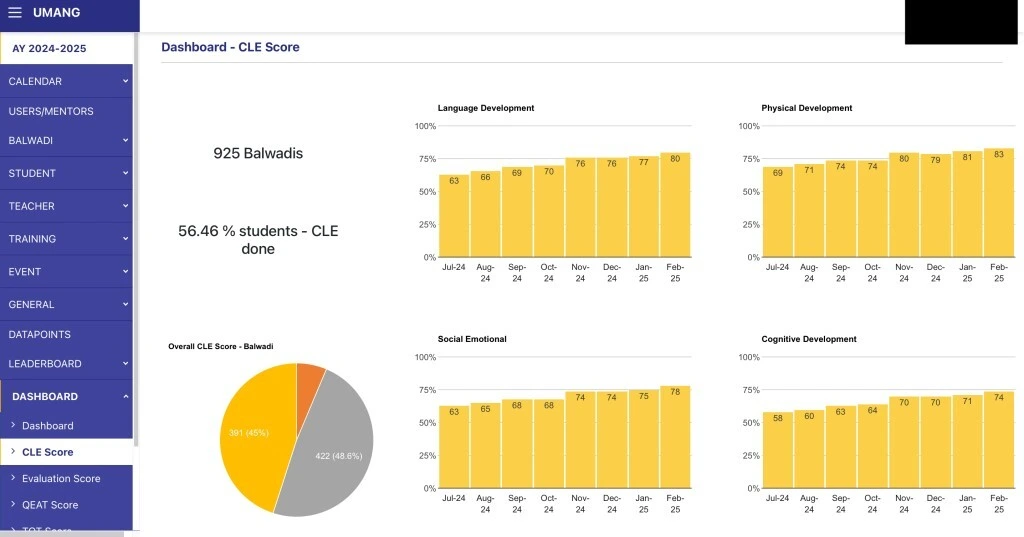

Within the classroom, the progress of each child is monitored using a tool called Classroom Learning Evaluation (CLE). While teachers were previously maintaining unstructured, narrative-based records, the assessment tool has since been developed to monitor children based on approximately 80 indicators across four domains. These indicators are aligned with the developmental milestones for children between the ages of three and six years. For instance, language development is assessed based on multiple competencies including verbal communication and early writing skills.

Each child is assessed monthly, and their progress is marked based on the following parameters: ‘Not Observed’, ‘Not Doing’, ‘Learning’, and ‘Can Do Easily’.

“Over time, teachers have become well-versed with the indicators. While earlier they felt that they were not looking at all these parameters, they have now asked us to remove the option of ‘Not Observed’ altogether, and to instead have ‘Learning’, ‘Learnt’, and ‘Doing Well’,” says Swati Bhatt, director of Vipla’s early years intervention.

Based on CLE data, the app auto-generates a graph depicting average classroom performance across each domain. If the score of the class or a particular child is not able to reach the benchmark for a specific domain, teachers can adjust strategies and introduce more activities and lesson plans to support learning needs. This information is also used to review programme design, in case similar patterns emerge across multiple Balwadis.

Along with the CLEs, a second evaluation is conducted every six months, where each child is assessed again. Based on CLE and biannual assessments, teachers can also observe how a child has progressed over time—something they previously had to calculate manually using information documented in different registers. A report card is then generated and shared with parents.

2. Teacher training and mentorship

Under the community Balwadi programme, each mentor is responsible for10–15 centres, while in the case of BMC Balwadis, this number can go up to 60. Mentors conduct a field visit to one Balwadi per day, observing both the classroom and the teacher. Here again, several indicators are employed to understand how a curriculum plan is being implemented, or where teachers require support.

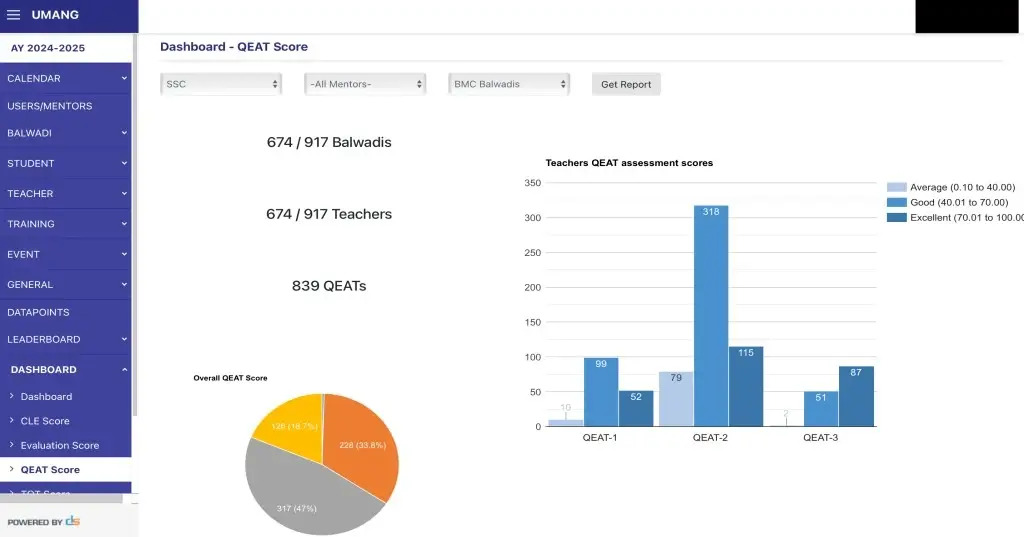

Mentors use two teacher assessment tools: the Teacher Observation Tool (TOT), a monthly monitoring exercise, and the Quality Evaluation and Assessment of Teachers (QEAT), which is conducted three times a year.

“We have indicators to gauge how a teacher is implementing curriculum plans, and to understand her needs and challenges. The QEAT is a more elaborate and qualitative tool designed to assess a teacher’s skills, approach, attitude, and knowledge of ECE,” says Swapnali. Mentors can track evaluations and teacher trainings through the companion Mentor App, which was rolled out in 2024.

Classroom observation and assessments inform the training that Vipla develops for teachers. “Teachers can check their QEAT scores on the Mentor app and their pre- and post-training test scores on Umang. Based on these, teachers have started initiating discussions with their mentors to ask for support,” Swapnali adds.

3. Getting the BMC and nonprofit partners on board

Starting in 2024, Umang was introduced across 1,100 Balwadis, including those under the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) and Mumbai Public Schools (MPS). This involved not just working with the BMC, but also with its nonprofit partners overseeing other Balwadis.

Amarja Kulkarni, manager at Vipla’s BMC Digitisation Programme, noted that the use of the app in the BMC system also raised compatibility issues. “For instance, in BMC schools, the focus is on ensuring that children continue their education within the BMC system rather than transitioning to private schools for mainstream education. Therefore, they did not want the report card feature because they felt that the teacher would hand over the report card and the parent might then move the child out of school.” As a result, a separate version of the app was developed for use in municipal Balwadis.

Getting higher-level officials to understand and commit to the initiative was crucial and became a key lesson. Involving the BMC in the development stage of the programme to figure out technical requirements and existing capacities from the outset could have helped make the rollout smoother, Pramod notes.

Convincing other nonprofits to use the app required extensive meetings and trust-building around Umang’s benefits. The BMC’s involvement through formal permissions and joint meetings facilitated this process.

What was equally critical was the acceptance of the app by teachers. Once their concerns were resolved through continued field and monitoring visits, Vipla was able to demonstrate the app’s value through the way in which it was used in classrooms.

Moving forward

Vipla is now also looking at the impact of teachers’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes on children’s learning, and using the insights from Umang to plan programmes. With an eye on eventually handing over the Umang initiative to the BMC entirely, another goal is to scale the app to other geographies and partner with other municipalities.

“Umang is more than a digital reporting tool; it has evolved into a crucial operational support system, enabling timely mentor interventions and equipping programme managers with real-time, data-driven insights for decision-making,” Swati says.

The organisation believes that the app has improved the quality of early education by simplifying progress tracking, enabling continuous mentorship, and improving learning outcomes. Based on its experience, Vipla offers the following advice to other nonprofits working on ECE: invest in user-friendly technology with on-ground support, and create a strong feedback loop between educators, programme designers, and government and nonprofit partners to ensure that interventions are adaptable and sustainable.

Based on inputs from Amarja Kulkarni, Pramod Nigudkar, Swapnali Thakurdesai, and Swati Bhatt.

Derrek Xavier contributed to this article.

—

About Amarja, Pramod, Swapnali, and Swati

Amarja Kulkarni is the programme manager for the BMC Digitisation Programme at Vipla Foundation. She has nine years of experience and has led BMC Balwadi digitisation and mentorship for nearly three years. Previously, she worked at SNDT’s Laboratory Nursery School and The Learning Curve preschool chain.

Pramod Nigudkar is the CEO of Vipla Foundation. With four decades of experience in the development sector, he has led social development initiatives at several organisations, including Care India and Pathfinder International. Pramod is passionate about sustainable impact and works closely with grassroots organisations and policymakers to drive meaningful change.

Swapnali Thakurdesai is the programme manager for community Balwadis at Vipla Foundation. She has been associated with Vipla for four years and oversees more than 40 Balwadis across low-income communities in Mumbai. Swapnali is dedicated to holistic child development and expanding early education access.

Swati Bhatt is the director of the early years intervention at Vipla Foundation. She has more than 25 years of experience in marketing, training, and early childhood education. Swati is a co-founder of The Learning Curve and a committee member of the AECED.

—

Know more

- Learn about taking a rights-based approach to education.

- Read this report on the inclusion of children with disabilities in ECE.

- Understand the importance of strengthening ECE globally.