The value of promoting entrepreneurship and self-employment for sustainable economic development is being recognised across the globe.

Start-ups and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) contribute significantly to the economic growth of a country by generating employment, bridging regional disparities, and improving the standard of living in various communities. Given the macroeconomic opportunities and the huge potential of the demographic dividend—India is projected to have 1.04 billion working people by 2030—the Government of India has been putting an impetus on entrepreneurship through programmes such as Make in India and Startup India. However, such efforts to make a difference may fall short if the working population is deficient in entrepreneurial skills and ambitions. Therefore, the need to make the population of India ‘entrepreneurship ready’ is urgent.

The graduate student enrolment rate in India is approximately 25–28 percent, depending on the method of calculation. This means that more than three quarters of the students who complete high school do not enrol in higher education and instead seek to enter the labour market each year. Most of these students do not possess employability skills and some lack even basic foundational skills. The youth unemployment rate in the country hovers around 25 percent.

Given the size of the Indian population, there is an urgency to equip the youth coming out of school with skills for seeking and generating employment. It would, thus, be of value to Indian society if entrepreneurship education starts at the high-school level.

Experiments in teaching entrepreneurship early

Currently, formalised education in entrepreneurship is often included at the graduation and post-graduation levels in India, and only at technical and management institutes. In most cases, these courses use conventional teaching methods and do not require students to participate actively. Questioning the practice that entrepreneurship education is only for those enrolled in college, the Entrepreneurship Mindset Curriculum (EMC) was instituted for classes 9–12 in Delhi government schools. The basic premise was that the development of entrepreneurial abilities and mindset through experiential learning in school would not only drive creativity, innovation, and passion to build something new or solve a social problem, but would also facilitate one’s career growth.

In 2021, to push the experiential component of the curriculum further, a large-scale programme called Business Blasters was announced. Students in classes 11 and 12 would work on a business idea that could generate profit and/or create social impact.

The programme was designed to build the awareness and skills required for entrepreneurship, including business acumen, curiosity, collaboration, communication, and overcoming the fear of failure. A seed capital of up to INR 2,000 was allocated to each team of 10 students. They were asked to come up with business ideas that would be useful, practical, profit-making, or that created social impact, and had potential for growth. The teams were mentored to improve upon their business idea before finally pitching it to investors. The six-month-long programme involved approximately 3 lakh students, 1,000 school leaders or principals, more than 10,000 teachers, 1,000 business coaches and mentors, and a special task force of the Department of Education. It was personally overseen by Delhi’s minister of education.

Given that it was a pioneering initiative, there was much that we learned during this programme with regard to pedagogy and implementation of entrepreneurial education with an experiential component. Here are some of our key learnings.

1. It opens up career choices

This large-scale programme on experiential entrepreneurship proved to be a real-life career choice laboratory. It helped students become more observant and aware of their surroundings, which led to a greater sense of curiosity and critical thinking around potential opportunities and possibilities. The students said that they were pleasantly surprised to learn that they could not only solve problems in their environment, but also earn a livelihood while doing so.

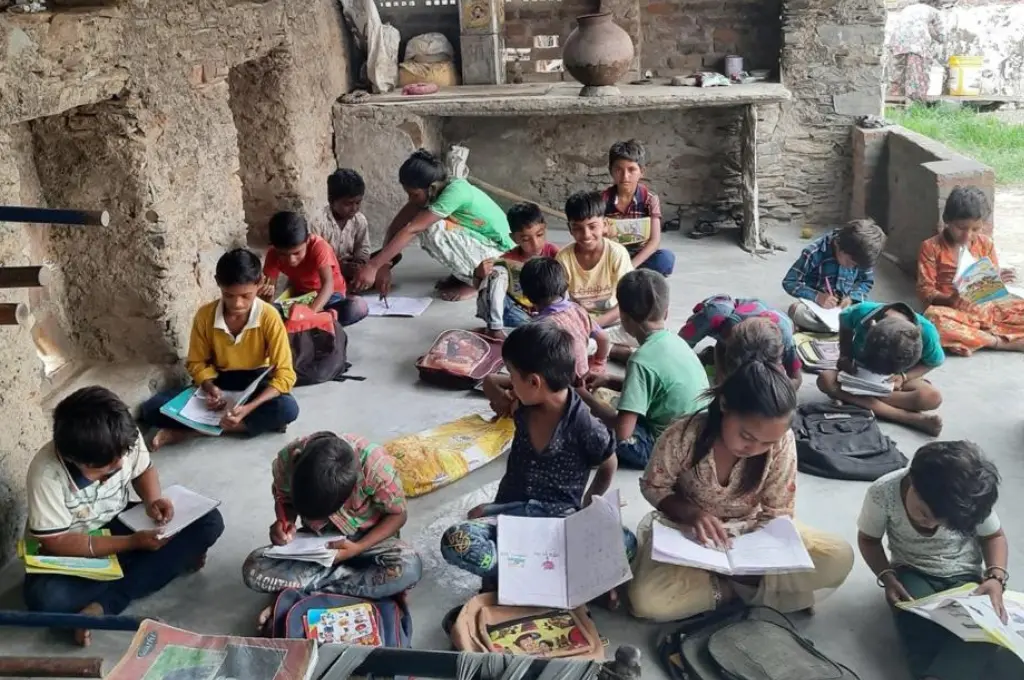

Most students who study in government schools in Delhi come from lower socio-economic backgrounds. The primary breadwinners in these students’ families are their fathers/mothers, who work as helpers, cleaners, mechanics, or in clerical jobs. Owing to their economic condition, these students are required to enter the labour market early (soon after school) to support their families. This leaves them with limited opportunities for higher education.

The Business Blasters programme helped them think of entrepreneurship as a legitimate and rewarding career option on completion of high school.

2. It helps increase employability skills and self-efficacy

Our conversations with students showed us that the skills and abilities gained in the process of running a business were likely to create a lasting impact irrespective of the outcome.

During the intense hands-on process of thinking of an idea, taking feedback, improving the idea, working with a team, making a pitch, building the product, and selling it, the students became aware of their strengths and weaknesses, developed confidence and improved self-efficacy, learned to take risks, and were able to effectively communicate their ideas and problem-solve.

No amount of classroom learning or participating in mock activities would have helped them build such skills. Students who were team leaders also expressed that, for the first time, they understood the importance of teamwork and collaboration, what it meant to face challenges in planning and execution, how to deal with conflict, and ways of navigating setbacks. Experiential learning made learning more relevant and real for most students.

3. It changes the mindset of stakeholders

Business coaches, teachers, and officers involved in the programme shared that seeing the participating students build and take charge of their businesses made them aware that these students—just like their own children—had potential. The various stakeholders involved in the programme shared that the students were better off when the support they were being provided moved away from the frame of charity and empowerment. Instead, it is better to focus on providing opportunities that are typically not available to the students.

Running an innovative project at scale

The time-bound nature of the project, the uncertainty caused by first-time implementation, and concerns about the safety of the minors involved helped us learn about large-scale project management of new ideas. Based on our analysis of the way the programme was run, it was clear that while policymakers can provide the vision, it takes a team of dedicated individuals working in collaboration to execute this vision. The on-ground team benefitted from the following approaches on the project:

1. Tight deadlines

The individuals who were responsible for project implementation shared that they appreciated the tight monitoring and deadlines during the process. It helped them focus while carrying out tasks that were unfamiliar and outside the scope of their work and expertise. They mentioned that in the absence of deadlines, it was likely that the teams would not have performed as well.

2. Autonomy

They further acknowledged that the sheer challenge of executing a large-scale project made them innovate and find their own resources to complete the work. It was not only the monitoring but also the operational autonomy (within situational and project constraints) given by the top team to the on-ground teams at various levels that led to the successful implementation of the project. The school teams also appreciated the freedom they had to shape the journeys of student teams that belonged to their school.

3. Shared learning

Being able to share concerns and solutions across schools made it possible to quickly learn and find solutions for sticky issues such as finding mentors and ensuring student safety. Not all problems could be envisaged by the central team and not all answers could be found within the implementing teams. Open communication in all directions helped in finishing the project and facing the challenges that came along the way.

One of the key challenges we encountered related to the network of business coaches, investors, and others who played an important role in creating a supportive environment for the students.

Several local entrepreneurs and BBA/MBA students agreed to take on the role of business coaches on a pro bono basis. In hindsight, however, we think the pro bono nature of the work needs to be revisited, and mentors need to be managed better as they faced several challenges during the course of the programme.

Mentors and coaches had trouble taking out time and travelling to meet the teams, and many of them ultimately dropped out. The coaches had little flexibility in scheduling the sessions, since the meetings with the students (who are minors) had to be conducted during school hours in the presence of the schoolteacher.

While mentorship may be provided pro bono, there is a need to find innovative ways to incentivise the business coaches, who spent two to three hours per week each month with the students. Use of group chats and video conferencing are ways to work around the distance and travel issues for continued support. But a few face-to-face meetings must be factored in while drawing budgets in the future.

For the long-term engagement of business coaches, identifying ways to support and reward them will become a relevant exercise as the programme progresses. Additionally, schoolteachers—several of whom were mentoring students on business ideas for the first time—need to be trained.

For more experiments like the Business Blasters programme, the wholehearted involvement of the school system and the bureaucracy cannot be overemphasised. Considering the current crisis of higher education and record high unemployment, such experiments, we believe, are worthy of emulation. A systematic analysis of the experiment’s success will help in better implementation of the next edition of such a programme.

—