Most of us familiar with the education landscape in our country know that learning outcomes have declined despite significant funding in the education space, teacher absenteeism is a major issue and the quality of instruction is poor.

India may have achieved near universalisation of primary education in 2015, with 96.9% of children in rural India enrolled in school in 2016, but enrolment and retention outside of primary education are low and attainment remains a critical gap.

With more than 1.5 million schools and more than 250 million student enrolments, India’s education system is among the most complex in the world. If a donor is looking to make an investment within this space, what, where and how can she support for maximum impact?

Sattva Consulting, with support from Asian Venture Philanthropy Network, undertook an extensive landscape study examining gaps, interventions and the funding ecosystem across different education segments and age groups in India. In this article, we highlight some of the key findings and recommendations from our research.

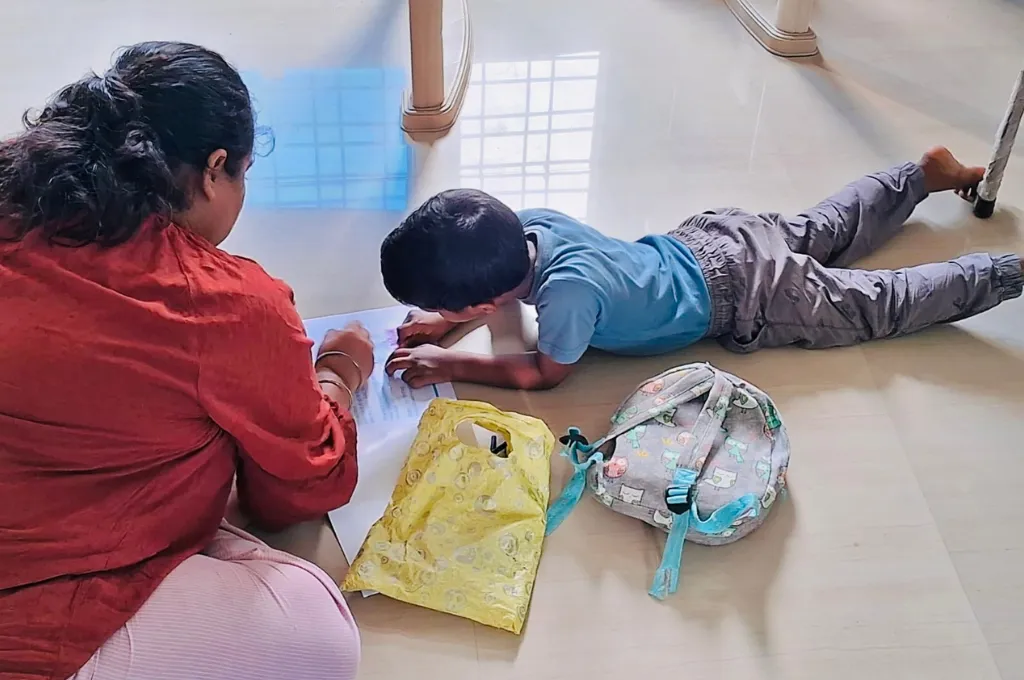

Photo Courtesy: Project Manhattan [CC BY-SA]

Changing trends in the funding education landscape

1. Early childhood education (ECE) and secondary education receive much less support than other segments within the education spectrum.

[quote]One out of every four children aged 3-5 years does not have access to early childhood education.[/quote] Both are critical areas in of themselves: intervening at the ECE stage can play a significant role in how the child performs in later schooling, while improving secondary education outcomes can contribute directly to a student’s employability and, with time, her economic security.

Part of the reason for this under-investment is a lack of awareness on the part of funders about these issues, as well as a general lack of clarity on what the outcomes are for both. In the absence of these, funding has remained lower than in other segments.

2. There has been a dramatic increase in the privatisation of education.

Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, the number of private schools surged by 77,063 nationwide, more than 6 times the increase in government schools (12,297). In the same period, government school enrolment decreased by 13.1 million while private school enrolment increased by 17.5 million.

Affordable private schools (APS), which are private unaided schools charging a fee under Rs 1500 per month, are seen as changing the landscape of how primary education is delivered in India both in rural and urban areas. There’s also a growing perception among parents that APSs deliver better quality than government schools, and at a lower cost than other private schools.

Solutions in the APS space are increasing in number, but given that this upward trend has been relatively recent, the rest of the ecosystem has yet to catch up in supporting these innovations. The APS market continues to be quite fragmented and unorganised for funding. While initiatives such as FSG’s PIPE (Improving Private Early Education in India) or SEED Schools’ APS fund are trying to correct this, it will take time. As a result, the APS space remains under-funded.

3. Thus far, ecosystem initiatives have been supported in pockets.

While a few multi-stakeholder partnerships have emerged there hasn’t been significant movement towards collective impact. Common needs such as curricula, standards, learning outcomes data, methodologies and tools for teachers, students and school management are lacking, resulting in duplication of efforts and sub-optimal solutions.

Public funding is insufficient: the government’s education budget was USD 51.5 billion in 2015-16 — about 2.7% of GDP. The total financial requirement for India to reach SDG 4 by 2030 is USD 2,258 billion, (averaging USD 173 billion per year).

Given these gaps, the sector needs ecosystem funding—for common standards and benchmarks, and foundational initiatives—as it offers greater potential to achieve impact.

Reading between the lines

Looking at the problem of education holistically, while important, can also be misleading, especially if you do not dissect it and take a closer look at the variables in play. What solutions work vary widely based on the interplay of a range of factors including gender, geography, caste, religion, age group and the sub-sector within education.

The unfortunate reality is that this space needs money everywhere. No problem has been ‘fixed.’ What’s needed is a deeper analysis of where the problem lies, what components define the nature of that problem, and therefore what approach and kind of funding will be most effective.

CC0 Public Domain

There can be a ‘right’ kind of funder for most gaps

Funding can serve different purposes and address different gaps within the system. For instance, there’s funding that jumpstarts a sector, for which you need a lot of investment capital going in. Then there’s funding that’s needed to support the replication of solutions in new geographies.

We are already seeing different players occupy these roles. For instance, DHFL is investing heavily in building the ECE sector, while many companies are supporting the expansion of interventions to new states. Our report on Funding Education with Impact highlights the various roles different types of funders can play within the education spectrum.

‘Anchor funders’ play a critical role in leading the way and bringing others along.

Ecosystem initiatives, despite creating impact at a sectoral level, can be tricky propositions for funding. First, they often result in outcomes that are hard to measure given their distance from the ground. This can lead to speculation around how effective an investment has been.

[quote]For every dollar you invest in ECE you get seven to 17 dollars of social returns.[/quote] Second, efforts that require collaboration across multiple players are difficult to execute. There needs to an alignment of goals and values, agreement on governance and process, and constant communication and stakeholder management.

Therefore, a donor that recognises the benefits of ecosystem-level initiatives irrespective of the costs, can act as the ‘anchor funder’ who takes the lead in driving the initiative and setting in place a framework that enables others to join. Having this also opens the door for companies, who may find it challenging to drive a collective initiative, but would be open to leveraging CSR funds as part of a larger ecosystem effort.

So, what will it take to influence donors to do this?

The education sector needs standardised outcome metrics and benchmarks and an acceptable model of measuring the value of an investment.

Today education is still largely measured on inputs. With corporates it’s easier to measure inputs because those are tangible. Though the conversation is shifting slowly to focus on outcomes, we need to get to a place where it’s the end goal for any CSR investment in education.

The ECE and secondary education segments in particular need well-defined outcomes as they are under-funded especially in comparison with, for instance, primary education. SSA played a critical role in creating momentum around primary education about two decades ago. The ASER report, which first came out in 2008, helped create standard metrics in a field that had none. Now with RMSA, we will likely see similar momentum in the secondary education space.

Policy directives create the momentum, following which measuring outcomes becomes important. And this clarity around measurement then helps attract investment.

The report, Funding Education with Impact was developed by AVPN in partnership with Credit Suisse and Sattva. It was launched at the recent AVPN India Summit.