Rapid urbanisation and the lack of planned affordable housing have led to a shortage of millions of urban homes. The Government of India estimates that there are 26–37 million families in urban India that live in informal housing, with poor living conditions. These largely belong to Economically Weaker Section (EWS) households and Low Income Group (LIG) households.

While a section of low-income households (e.g., the lower end of EWS) cannot afford to either buy a privately constructed home or improve their homes without significant help from the government, a large number of the upper end of EWS and LIG households can, provided they get a housing loan.

[quote]There are 26–37 million families in urban India that live in informal housing.[/quote]While there has historically been a lack of access to housing finance for these customers, the market has seen the emergence of affordable housing finance companies (AHFCs), which recognise that even though low-income customers may not have reliable documentation, they have reasonable, steady incomes. Since 2012, the National Housing Bank (NBH) has refinanced and acquired new licenses for 16 AHFCs, and the sector has managed to serve thousands of low-income households that would otherwise have found it difficult to access financing.

FSG’s Inclusive Markets team undertook a study to document the opportunities and challenges facing the low-income housing finance market. The findings are a synthesis of a three-phase approach:

- Mapping and understanding activity in affordable housing finance

- Investigating challenges and opportunities for AHFCs and developers

- Developing a set of recommendations with inputs from various experts and stakeholders

The researchers distilled information from interviews conducted with 26 AHFCs, 22 affordable housing developers, 25+ customers across six cities, 20+ experts in affordable housing and housing finance, and eight primary lending institutions apart from AHFCs lending to low-income customers.

The FSG team conducted multiple in-person interviews with these entities to understand their lending models, business approaches, future aspirations, challenges, and opportunities.

The following are their findings

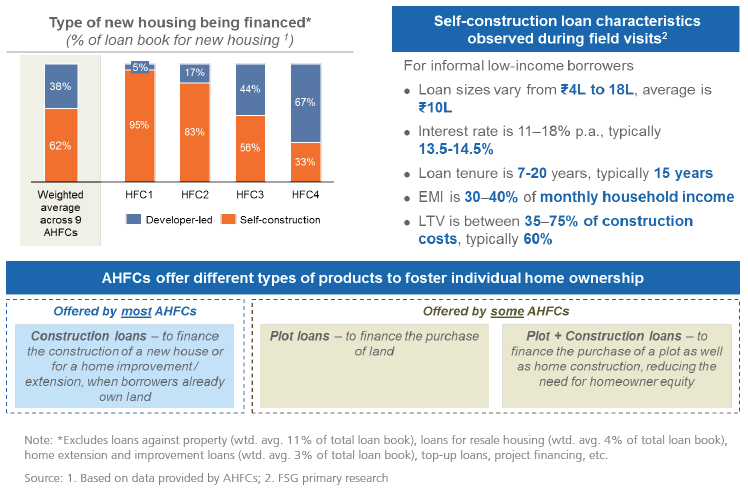

A significant volume of the new housing being financed by AHFCs is ‘self-construction’ of standalone housing, where the family uses a loan to construct their new home with the help of a contractor. This is typically located on the outskirts of large cities, as well as in tier II and III towns.

Figure 1: Type of new housing financed and loan characteristics

Some self-construction customers are fortunate to have ancestral land at their disposal; a vast majority, however, seems to comprise families that saved up for years to buy land, and instead of waiting many more years to save up for construction, they now use housing finance to construct their home. Some AHFCs have also made ‘plot and construction’ loans available to customers who want to purchase land and then construct a home.

Many self-construction homeowners are unable to find apartments in locations of their choice; more importantly, they show a marked preference for owning land. This permits them to build an extension or an additional floor in the future to accommodate a larger household or to generate a supplementary source of income by renting out the additional space.

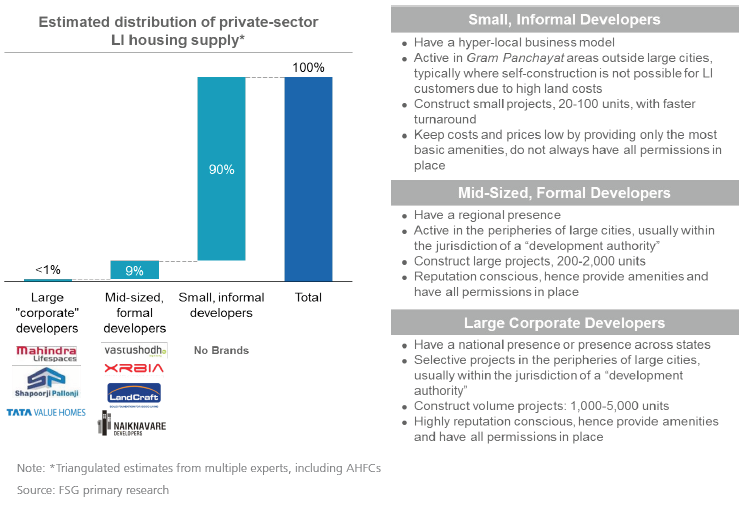

Where self-construction is less affordable, AHFCs are helping low-income customers purchase apartments. Such apartments are typically supplied by ‘informal’ developers that construct small projects in localities with high demand, typically in Gram Panchayat areas, just outside cities. They are able to supply this housing at lower prices because they follow Gram Panchayat norms that allow for greater use of space.

Figure 2: Developer-led supply of affordable housing by type of developer

Large and mid-sized formal developers have largely been unsuccessful in supplying affordable housing to low-income customers as they tend to be more expensive and construct large projects that are further away from the city in less desirable locations.

These distant locations also may lack infrastructure and require large investments, which further shrink the already low margins of such projects.

Related article: Using fintech for financial inclusion

One of the challenges for AHFCs is the loss of good customers. Once customers have a track record of regular payments, banks and larger HFCs are taking them over by providing loans at better rates. This may lead to some AHFCs deprioritising smaller customers since the cost of acquiring these customers is the same as the cost of acquiring larger customers, and in a short loan tenure regime, a larger customer is economically much more attractive. To address the impact of balance transfers on AHFCs, lenders could be required to pay the AHFC a fee for ‘sourcing’ the customer.

Recommendations for shaping a more inclusive and robust market

Going forward, the market needs to be nurtured and existing players require support to ensure sustained access to Affordable Housing Finance for EWS and LIG households.

Credit linked subsidies (CLS), an interest subsidy scheme under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), have benefited thousands of end-users, but it does not seem to have improved the affordability of homes. Homeowners and potential homeowners are usually aware of the scheme but are unsure of the criteria and whether they are eligible for it, and do not factor the subsidy amount into their home purchase decision.

Picture courtesy: FSG

[quote]Homeowners are aware of the scheme but unsure of whether they are eligible for it.[/quote]A significant number of low-income households are also ineligible from accessing CLS benefits because of the location of their new homes. The bulk of low-income housing is constructed on the peripheries of urban areas, which are not eligible for CLS until state governments ‘notify’ these areas. In other cases, homes are constructed where building sanction plans are not necessary by local guidelines for houses under a certain size. However, since CLS requires an approved sanction plan, it is challenging for these homeowners to get CLS approval.

The ambiguity and complexity around CLS has led some customers to hold the AHFC or developer accountable if their application is rejected, which has in turn disincentivised AHFCs to market CLS.

However, CLS could help a significant number of low-income households purchase a home or afford a larger one if:

- There is a pre-approval process; customers would then know for certain that they would receive the subsidy

- More semi-urban areas are included in the eligibility criteria

- The requirement for sanction plans for self-construction on small plots is done away with

- Additional costs such as GST, stamp duty, and mortgage registration fees for small homes is reduced

Related article: When does a slum stop being a slum?

14 million urban households in India live in slums with poor infrastructure and living conditions. Many of them invest in improving these conditions, but it is hard to find financial institutions willing to give them loans, despite the fact that the home loan opportunity in notified slums itself is 23,000 crores*.

[quote]It is hard to find financial institutions willing to give loans to households in slums.[/quote]Financial institutions that are interested in lending for home improvement in slums are not sure about the legality of doing so. Legislation in a few states seems to indicate it is a criminal offense. For example, in Maharashtra, financing construction in notified slums is a criminal offence under the state law, and AHFCs are concerned that they may be prosecuted for doing so.

On the other hand, the government seems to want to support home improvement in slums: under the urban component of the Swachh Bharat Mission, the government provides a subsidy for the construction of individual toilets irrespective of land ownership/tenure security.

Some of the properties may be mortgageable, but it may not be possible to use the home as collateral because loan recovery may not be feasible due to low marketability of properties in slums. AHFCs that are interested in lending for home improvement are then concerned about not being able to repossess the house under SARFAESI** or sell it after repossession.

Housing finance for home improvement/extension in slums would benefit low-income customers most affected by poor living conditions. This could be facilitated by explicitly allowing lending to households in slums, starting with households that own land and households that live in notified slums.

The Beneficiary Led Construction (BLC) vertical of PMAY provides financial support for families who own land but do not have pucca houses or have small houses (below 21 sq. meters). While the subsidy is significant, most households still require a loan to construct a house.

Urban local bodies that manage this scheme look to public sector banks to finance these customers, but these banks are usually not interested in lending to EWS households for whom they cannot readily assess repayment capacity.

Some AHFCs and many other lenders are interested in servicing such loans but find it difficult to identify BLC beneficiaries who want a loan. Current beneficiary lists contain applicants, not customers who have been approved. Also, customers who have been approved may not be interested in constructing at this stage and hence may not need a loan.

Urban authorities working with BLC beneficiaries could provide them details of lenders who are interested in financing them and have a local presence. To encourage financing these segments, NHB could provide additional refinance lines specifically for them.

- To incentivise supply from larger formal developers, land could be made available to them by housing boards or by demarcating zones for affordable housing projects

- An expedited process for approvals would also help these developers

- Finally, relaxing some of the restrictions on the 80-IBA tax exemptions and providing pre-approvals would allow developers to use the exemptions and reduce prices for end-customers

* Source: FSG

**The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002

To read the whole report, click here.

Ayesha Marfatia contributed to this article.