As India struggles with an unemployment crisis, its microenterprises—units with fewer than 20 workers—can become significant engines for job creation, concluded an October 2019 report.

- India has failed to increase the scale of the microenterprise sector substantially;

- A majority of India’s microenterprises are tiny and run with fewer than three workers;

- The sector shows good growth in labour productivity but with very low wage levels.

These are some of the significant conclusions of the study by Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment and the Global Alliance for Mass Entrepreneurship, which looked at all non-farm microenterprises, except the construction sector (National Sample Survey covered manufacturing and services sectors).

India’s microenterprises can become significant engines for job creation. | Photo courtesy: Pau Casals on Unsplash

Microenterprises create 11% of jobs in India, as per the report, which is based on the Sixth Economic Census and National Sample Survey data (67th and 73rd rounds). This is significantly less than the 30%-40% in other developed and developing nations. This can be changed if state and central governments help microenterprises scale up their operations and become more gender-inclusive, the study has said.

Related article: An untapped opportunity in employability

There is also a problem with women’s participation in India’s microenterprises: Social and market factors are loaded against them affecting their productivity, as we explain later. Women run 20% of all microenterprises, make for 16% of their workforce, and contribute 9% of aggregate value-added in the sector, as per the 2015 figures cited in the study. But in six years to 2015, their share in the ownership of micro units and value added did not increase and their share fell two percentage points.

Between 2010 and 2015, microenterprises in the apparel and education sector registered the highest growth (5% or more CAGR) in rural India. In urban areas, education, health and sale of cars and motorcycles reported the most growth. At this growth rate, microenterprises in the field of health and education together create around 260,000 jobs every year in India, the study noted.

The study analysed geographical distribution, demographics, gender (employment and enterprise ownership), industrial distribution, labour productivity and wages.

Most microenterprises have three or fewer workers

Over six years to 2015, employment in non-farm microenterprises grew from 108 million to 111.3 million with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 0.6%. Their aggregate gross value grew at 9% CAGR, from Rs 7.4 lakh crore ($104 billion) to Rs 11.5 lakh crore ($162 billion).

But Indian microenterprises have “low output elasticity of employment that is seen in the organised sector”, said the study. This implies that despite effective growth in value addition in the sector, job opportunities grew little.

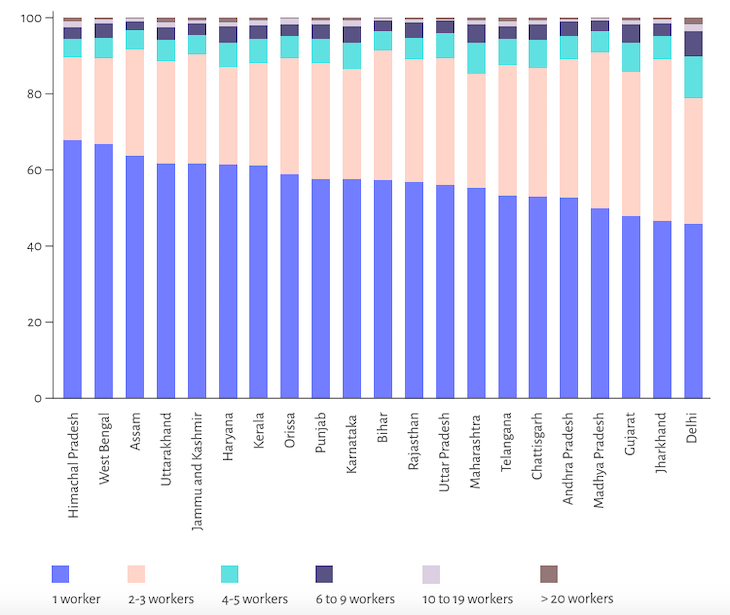

Nationally, 55% of the enterprises surveyed operated with only one working owner and no paid or unpaid workers while another 32% operated with two to three total workers (paid and unpaid), the report noted.

There are state-wise variations in the scale of operation of microenterprises: In West Bengal and Assam, nearly 90% fell within the two smallest size classes (upto 2-3 workers). In Delhi and Gujarat, most tend to employ upto 4-5 workers.

Enterprises that employ around 4-5 to say, upto 20 workers are the promising part of the microenterprise sector. They are likely to grow if given the right support and can create millions of jobs.

“Very tiny microenterprises with one or two workers are more likely to be ‘reluctant entrepreneurs [those content to do small business]’,” said Amit Basole, co-author of the study and faculty at the Azim Premji University. “So they may not be able to grow much. But enterprises that employ around 4-5 to say, upto 20 workers are the promising part of the microenterprise sector. They are likely to grow if given the right support and can create millions of jobs.”

Between 2010 and 2015, retail units in the microenterprises sector had the largest share of firms and workers (30%) in rural and urban India. The other large employers in rural India were micro units engaged in transport, apparel, tobacco, and food products. In urban areas, restaurants, apparel, education, and wholesale trade employed the most workers, the report noted.

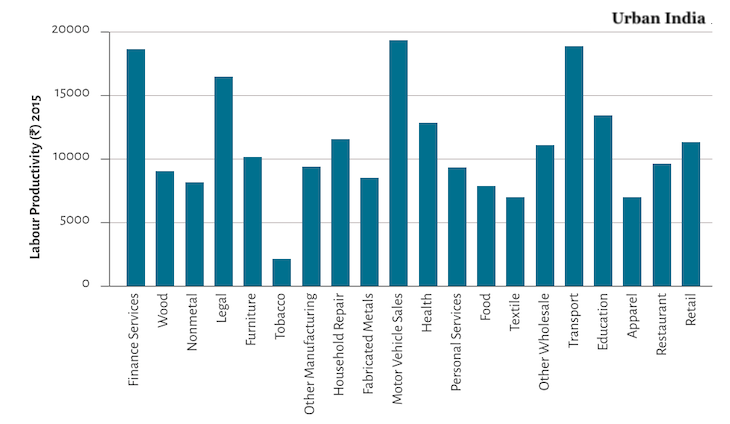

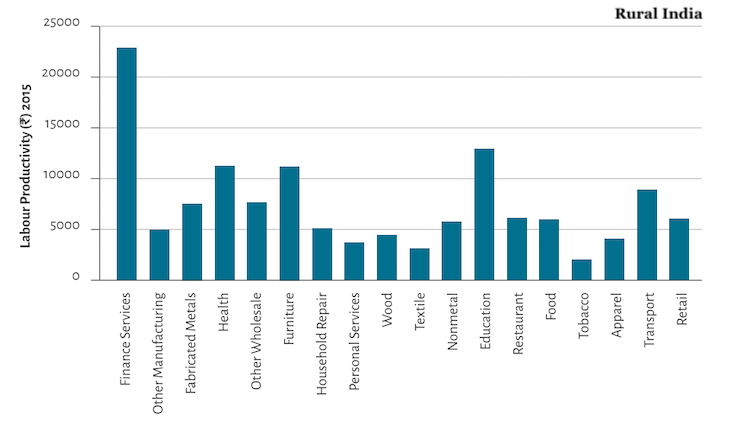

Education sector paid the best wages, tobacco least

In 2015, among microenterprises that were large employers, the lowest wages and productivity were reported by the rural tobacco industry. The average monthly wage here worked out to less than Rs 5,000 per worker per month, as per the study. The highest productivity was in the education sector in rural areas—nearly Rs 13,000 per month per worker—as was the highest wage level (Rs 10,000).

But urban areas fared poorly. None of the large employers in cities and towns showed average monthly wages of Rs 10,000 or above. Most paid Rs 6,000-Rs 8,000, said the study.

“In part, the reason is that the level of productivity is still low despite growth—wages generally cannot exceed productivity,” said Basole. “The other reason is that even if productivity grows, this does not necessarily translate into equivalent wage growth because there is a lot of surplus labour in the informal economy. This prevents wages from rising.”

Smallest units performed best

In terms of their contribution to India’s economy, it is the smallest scale of microenterprises that increased their share in gross value added and employment. That the larger ones failed to do so is “worrying”, the study said.

Related article: What happens when investments targeting women’s microbusinesses go to men?

Up to 60% of all unorganised sector enterprises in 2010 were single-worker enterprises and their share increased 2 percentage points to 62% by 2015. Single-worker firms and firms with up to three workers accounted for 93% of all firms in 2010 and 94% in 2015.

The sector faces several challenges when it comes to scaling up operations. These include low levels of productivity and wages, lack of access to credit, infrastructure and markets, and punitive regulation, according to Basole.

Firms with 4-5 workers are 50% more productive per worker than their smaller counterparts while the wage rate does not vary much across size classes, the study noted. The increase is seen mostly when units go from 2-3 workers to 4-5; beyond this, “surplus increases more slowly and even declines for the largest size class”, the study said. Larger firms are not proportionately more productive perhaps due to infrastructural constraints in the unorganised sector, the study noted.

Government policies aimed at the growth of this sector will work only if they are sustained and realised in coordination with other policies

Government policies aimed at the growth of this sector will work only if they are sustained and realised in coordination with other policies, said Basole. Schemes like MUDRA, which provides loans up to Rs 10 lakh to non-corporate, non-farm small/microenterprises, have “focused too much on very small loans, which tend to not give sustainable growth in the enterprise”, Basole said. So the focus needs to be on scaling up microenterprises to the point where a typical enterprise employs 4-5 workers, not 2-3, he added.

Why women are at a disadvantage

Women’s engagement with the microenterprises sector has not been satisfactory, as we mentioned earlier. The scale of operation is smaller for women than men, the study found. Upto 216,000 of women-owned microenterprises of 8 million (or 2.7%) hired three or more workers, 45,000 hired 6-9 workers and 25,000 more than 10. But for men, the comparable numbers were larger: 3 million hired three or more workers, 500,000 hired 6-9 and 233,000 more than 10, the study noted.

Further, in 2013-14, more than three-quarters of total workers employed (13.4 million) by women-owned establishments were female. This showed a “high tendency for women to work with other women”. Manipur (91%) and Kerala (90%) had the most in terms of women-owned enterprises that employ women.

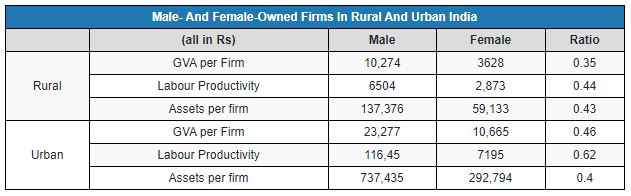

In urban India, the gross value added per firm for female entrepreneurs was 46% of male-owned firms, labour productivity was 62% and assets-owned 40%. In rural areas these figures stood at 35%, 44% and 43% respectively. Both in urban and rural India, 10 industries accounted for over 90% female-owned firms.

“Women tend to operate smaller enterprises, tend to be home-based (which means they cannot expand easily) and tend to work with other women,” said Basole. “They often do not own assets (such as titles to land or home) that can be collateralised for credit.”

Women also have to juggle work with domestic responsibilities, making it harder for them to invest enough time in the enterprise. They also face discrimination in the market–getting a lower price than male entrepreneurs for the same product, said Basole.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism nonprofit.