“This can’t go on like this”

“But, what is the way ahead?”

“In the absence of schools, is this our bread and butter? We have a commitment to our teachers, to our children, right?”

“But, at what cost?”

Voices rose. Tense moments passed. Fatigue was evident in everyone’s voice. It was five months into the national lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic, and two months into the online learning programme that our organisation, Kanavu, had launched. Though my co-founders and I sat together in the room, we had never felt further apart as we questioned our choice to start online learning in rural communities. We were questioning everything: how we were doing it, how much time was being invested, and how that connected to the purpose of our organisation.

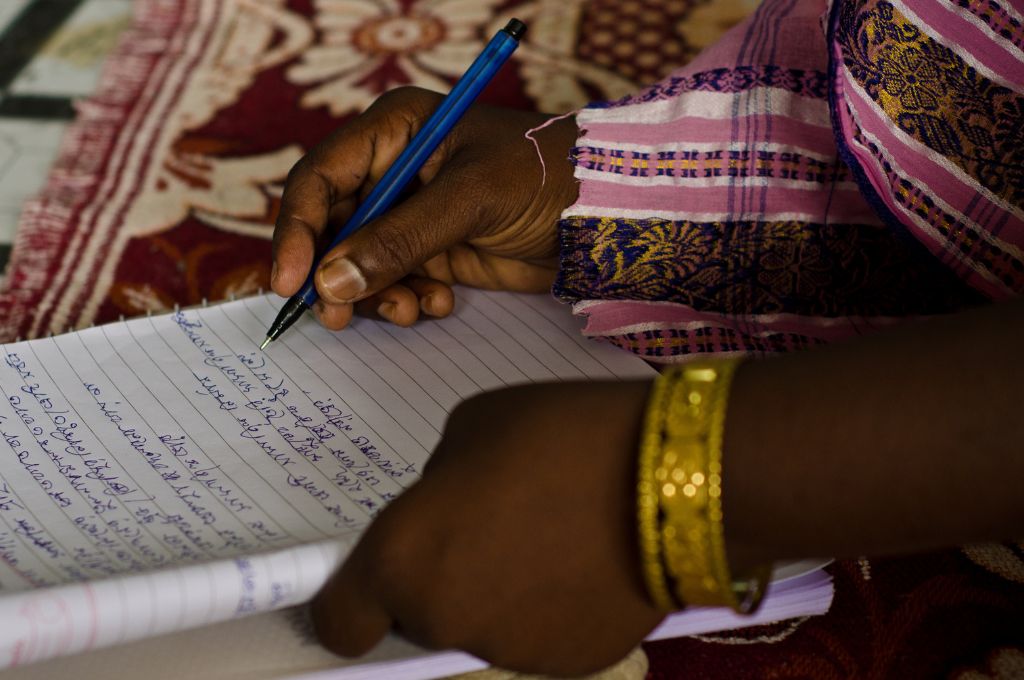

Two years ago, in 2018, a small team of four with a dream of a ‘transformed’ rural India came together to set up Kanavu. Kanavu works with 55 teachers, five school principals, and more than 20 women from local communities, who together serve about 1,300 children. As a team, we focus on training teachers—on content, pedagogy, and leadership skills. We also run a leadership programme for principals to build a strong school culture.

Shifting gears to navigate the pandemic

In March 2020, as we stepped into what seemed like a stable quarter of our second year in existence, the pandemic happened. Shortly after the lockdown was announced, we found ourselves shifting gears. At first, we began responding to community needs by fundraising for cash transfers and distributing dry rations to the families we worked with. With schools remaining shut, we felt a growing conviction that children must continue learning. Thus, Kathir (meaning ‘ray’) was born: a project that supported our teachers and students with continued learning opportunities, despite the pandemic. This, in the current context, meant remote and asynchronous learning. Simply put, we sent children videos to learn from, which they could access at their convenience based on when they could access a mobile phone. The expectation was that they would learn by watching the video, complete the task given, and share it back with the teacher via WhatsApp.

In June 2020, we decided to focus on bridging the technology gap among teachers, many of whom were not comfortable using technology-based solutions to teach. We would then move on to create content that could reach students through WhatsApp. And so, we began raising funds for recharging mobile data plans and securing used digital devices for our teachers. We were also generating learning videos for every grade on a daily basis. With all four founders being Teach for India alumni, the ‘teachers’ within us rose to the occasion.

We made grand plans for age-specific content. Students and parents were now using local materials to learn; children’s science experiments could employ materials found at home, and stones and shells were being used as math aids. Parents learnt child development theory through short videos that helped them facilitate learning for children in kindergarten classes. Learning videos and completed worksheet photos started pouring in. Our phones were buzzing with teachers seeking help to figure out WhatsApp—most of them had never used a smartphone before. And, we were also simultaneously working with principals to increase student access to online learning—a massive challenge in the rural communities that we were working with.

Our seemingly perfect pivot failed

Everything we were doing seemed like a perfect mix for feeling both a sense of satisfaction and achievement. Except it did not feel that way. Exhaustion and a feeling of inadequacy quickly crept in. Sending tasks to students every morning meant that we began working as early as 5 AM on most days. This was necessary because it allowed us to record videos, create worksheets, send out tasks, and spend most parts of the morning problem-solving so that we could reach more students.

Our stakeholders—teachers and principals—were fighting their own battles as well, ‘work from home’ being among the toughest. There was constant fire fighting to help teachers build routines so they could sail through a day of online learning while continuing to meet the demands of running a rural household during a pandemic. Given the increase in challenges in online learning and uncertainties of the pandemic, we became shock absorbers for the teachers’ rising stress levels.

Efforts to build the organisation, raise funds, and connect to different networks were only made based on need. There was a growing inability to do what was important; we only did what was urgent. We kept telling ourselves that these were teething problems and that we would soon settle into a routine. Except we didn’t.

In about two months, we became sure that we were failing. Keeping a project like Kathir alive, while meeting the demands of running an organisation and trying to do it all was a perfect recipe for failure.

We asked ourselves if we could do this well, rather than asking whether we were the only people who could do it well.

Upon taking a step back and exploring what was going wrong, we saw different themes emerge. We had signed up to do way more than the four of us could handle. We weren’t focusing enough on Kanavu as an organisation. We were exhausted; and, we hadn’t focused on fundraising. The bulk of the time invested in creating tasks left us with little time to engage directly with our teachers and principals. This left them struggling to cope with the daily demands of dwindling student numbers, or sometimes, poorly understanding the task sent to students. This also led to a drop in motivation and a culture of negativity among our teachers. Doing calls with school teams helped us see how much our teachers wanted us to engage with them and handhold them through the learning process. As a team, we were waiting on a funding renewal, without which we would have run out of all funding for Kanavu by the end of 2020. This put immense pressure on us, making us question how we were spending our time. Some of us were hopeful about the funding renewal, while others believed that we needed a backup plan. As a result of this singular focus on ‘Kathir’ as a programme, we wondered if our very existence was in question.

We agreed that we were failing and that it was costing us our own well-being, as well as that of our team and organisation. Not to mention, our sustainability was at risk.

Yet, we had differing opinions on how to solve this problem. Would we stop running the programme in this manner? Would we build skills in our teachers to create content? Would we hire more consultants? What would the implications be for our budget?

In hindsight, we realise that we went down this path recognising a need, and also recognising our own ability to fill that need. And so, we asked ourselves if we could do this well, rather than asking whether we were the only people who could do it well. Yes, we had roped in volunteers who created about 20 percent of our videos for us, but that wasn’t enough to give us the time and bandwidth to focus on Kanavu.

My journey through this failure

Personally, this failure wreaked havoc across my life and work. I found myself struggling to meet the demands of being a mother to a 3-year-old and a dog, an entrepreneur aiming to run a sustainable organisation, and a leader aspiring to learn and grow. I found myself feeling a greater sense of inadequacy.

I was in overdrive, trying to speed up the time it would take me to complete different tasks in an attempt to conquer my to-do list. I was unavailable to people in any way, at work or in life. I wasn’t listening deeply enough to the school principal who was sharing her concerns about online teaching, or to the teacher who was facing a similar struggle as mine in trying to balance her role as a mother and an online teacher. I was looking for quick solutions that got us past that day. I didn’t listen deeply enough to my co-founders who were sharing opinions that differed from mine or solutions that I hadn’t imagined. Not listening deeply enough created a disconnect and a growing sense that we weren’t designing creative and empathetic solutions.

While we continued to be present in learning spaces and applied for a renewal grant, we knew that both partnerships and funding had taken a hit.

For the first time in a decade of working with people, I wondered if I wasn’t cut out for a role that involved working with people. I found myself not having any energy to think creatively about the problems at hand. I allowed myself to believe that creating content myself saved me the time that I would otherwise have to invest in checking the quality of volunteer-created content. So my to-do list grew, and I wasn’t making time to tap into an existing support system or build a new one.

All of this affected both me and the team deeply. It showed up as exhaustion, disconnect, avoiding difficult conversations, slower decision-making, and less joy at the workplace. While we continued to be present in learning spaces and applied for a renewal grant, we knew that both partnerships and funding had taken a hit. For a two-year-old organisation, this could hurt us in the long run.

Our teachers, school principals, and partners experienced us as being ‘busy’ and hence, ‘did not want to trouble us further’. This meant that we weren’t in touch with what was happening with them. This realisation finally brought us to a point of acceptance: “we could not go on like this”.

What we learned

1. The big “f” word

This difficult period shattered our belief that passion meeting purpose alone could carry us through any challenge. It has since introduced the big ‘f’ word into our decision-making: feasibility. As part of our working process, we have started to ask ourselves: Is this feasible? How do we make this feasible? Just asking this seemingly simple question is helping us declutter. We are able to look at what’s a ‘good to do’ and a ‘must do’. It has helped us think critically about how we spend our resources and time.

2. Collective reflective spaces

This failure underlined the fact that reflective individuals coming together alone doesn’t necessarily result in a reflective team. While each one of us grows aware by reflecting, we also need spaces to come together as a team to reflect and articulate those reflections. Doing this will help us get on the same page, make tweaks accordingly, and move on.

3. Anchor in joy

A big lesson has been that focusing on the founding team’s well-being and joy ensures the organisation’s sustainability, especially in its early years. Creating spaces for celebration, acknowledging efforts, and sharing impact give people the energy to move forward.

We know that in the journey of a young organisation, there is no happily ever after, but we are grateful for the wisdom that comes from failing spectacularly.

These three insights have helped us imagine what’s next. We have brought on a consultant who can support content creation for student tasks. We are instating a rigorous process to find and invest in the right people to volunteer with us. And, we are focusing on orienting them, sharing feedback on their work, and building quality in the content generation process.

We are still struggling with reducing the scope of our work in order to balance the ‘feasibility’ question with our ambition to fulfil our vision. Then, there are moments when we see one of our volunteers grow more confident, or when we’re able to invest time in what we think will help move Kanavu to a stronger space in five years.

We know that in the journey of a young organisation, there is no ‘happily ever after’, but we are grateful for the wisdom that comes from failing spectacularly.

This article was published with EduMentum, a strategic partner in Failure Files, a special series on IDR where social change leaders chronicle their failures and lessons learnt.