Evolving from colonial and post-colonial industrial and trade policies, today the Indian textile industry directly employs an estimated 45 million people, making it the second largest source of employment in India. With an extensive jurisdiction stretching from farms to ready-made garments, the textile industry’s contribution to India’s GDP increased from 1.69 percent in 2011-2012 to 2.3 percent in 2016-2017, as per the National Accounts Statistics.

India’s unique and lucrative position in the global textile and garment production network is often attributed to its proximity to agriculture and production networks, such as those for traditional handloom and embroidery crafts. But the highest value addition to raw materials and textile occurs at the garment manufacturing stage, through a coordinated but geographically decentralised mix of dying, cutting, stitching, and ancillary tasks such as embroidery and buttonholing. In India, these labour-intensive tasks have become concentrated in manufacturing clusters with specific product specialisations. For example, Ludhiana has emerged as a hub for winter knitwear and Bengaluru is a hub for menswear and woven garments.

Related article: Women, work, and migration

Apparel manufacturing hubs are few and far between, and output demands are high. Consequently, the local labour supply is supplemented by a moving workforce. More than 70 percent of the workforce in the biggest hubs—NCR, Tiruppur, and Bangalore—comprises of circular or temporary migrants,1 making migration an essential factor for production.

There are several instances that hint at the over-reliance of the sector on migrants and also expose the vulnerabilities that migrant workers face in the largely informal textile industry: the mass exodus of migrant workers from Gujarat after horrifying instances of violence in 2018; the reduction in output from the Tamil Nadu manufacturing clusters when migrants returned home to vote; job crunch in the informal economy following the implementation of GST and demonetisation; to name a few.

What makes migrants vulnerable?

Asian firms tend to rely on a short-term contracting system to meet demand and the global ‘just-in-time’ production model which accommodates fashion seasons. Globally too, the textile industry is buyer-driven, characterised by high levels of cross-border contracting and subcontracting, allowing firms to have flexible specialisations and meet fluctuating demand. During low seasons, workers’ contracts are easily terminated, making contract labour a fundamental mechanism for producing flexible and profitable outputs.

Most migrant workers are doing the same jobs as local labour for lower wages, in harsher living conditions, and with little support mechanisms.

In India, the short-term contracting system has become uniquely linked to migration patterns. A combination of contracting and the use of migratory labour makes business viable and labour subdued and manageable for manufacturers and subcontractors (thekedaars). The thekedaars, who effectively neutralise the employer-employee relationship, make access to redressal mechanisms non-existent for workers, and allow local manufacturers to wash their hands off any obligations towards the work or worker.

Labour migration patterns are fluid and seasonal: workers are easy to hire and fire, and a fragmented labour force comes with a minimal risk of unionisation. Most migrant workers are either intrastate rural migrants or migrants from neighbouring states, doing the same jobs for lower wages than local labour in far harsher living conditions and with little to no legal, linguistic, and social support mechanisms.

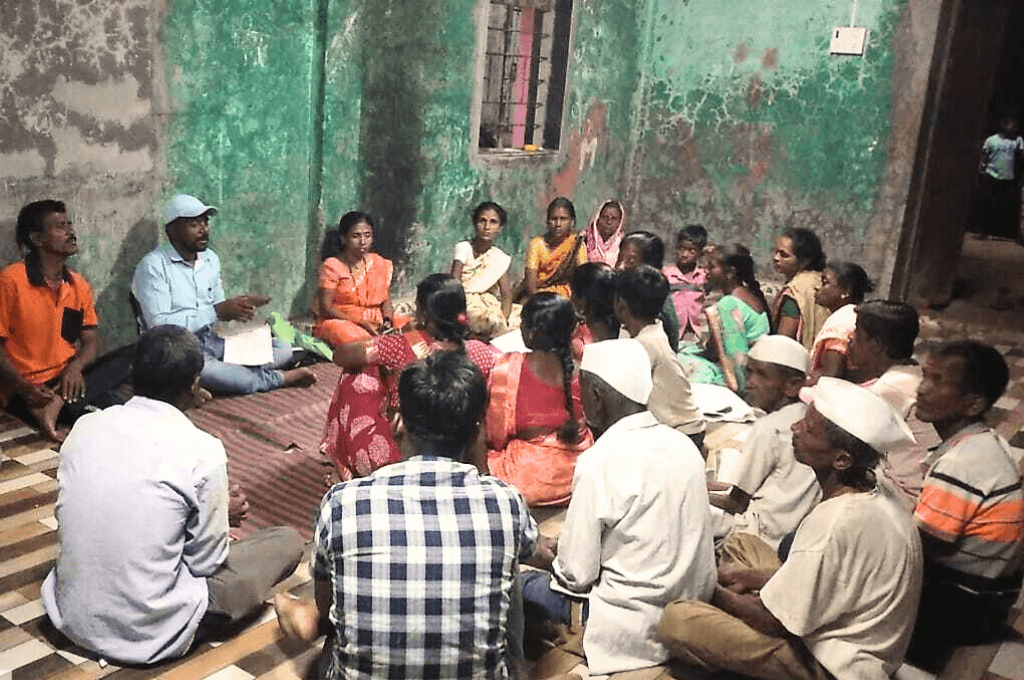

A large portion of migrant workforce belong to marginalised communities, and this becomes the basis of their exploitation. | Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Identity and exploitation

A recent study confirmed that 95 percent of the surveyed NCR cluster workforce belonged to marginalised communities. A similar demographic profile was reported on Bangalore’s women workers. The workers’ socio-cultural positions become the basis for exploitation.

The Sumangali Scheme—a model that is illegal but not yet eradicated, popular in Tamil Nadu, and targeted at employing (and exploiting) teenage girls—is possibly the starkest example of the intersection of caste, class, gender, migration, and informality. Mills recruit 13-18-year-old Sumangalis (unmarried woman transitioning to married life) to manufacturing centres from remote villages as ‘apprentices’ under a three-year contract (until they come of age). Completing the contract guarantees a lump-sum amount, which is typically used for eventual dowry payments. However, mill work does not require a three-year apprenticeship; the apprenticeship tag merely legitimises the ill-treatment meted out to young, vulnerable female workers. On top of this, 60 percent of Sumangali workers belong to Dalit communities, and are paid much less on account of their caste and gender.

Related article: Understand migrants’ lives to address their needs

For the female workforce in the textile industry, work is simultaneously linked to movement and confinement. Women move with their families to garment hubs, only to take up home-based work such as thread-cutting jobs. More often than not, female child labourers assist their mothers in home-based garment work to supplement household income, at the cost of their childhood. Sexual exploitation of female workers is also rampant, so for female factory workers, safety translates into confinement and policing.

Still, the migrant, the worker, and the woman remain invisible to the state’s policies, provisions, and protection but are possibly the most socially surveilled economic contributors.

The policy perspective

The Government of India has several schemes for skill development and capacity building for informal or marginalised workers. Under ‘Make in India’, there are also many investment opportunities that highlight the role that social entrepreneurship can play to enable the sector to prosper.

For CSR or policy initiatives to truly find effect in India, it is critical to recognise migrant workers’ rights and freedoms.

However, these schemes and initiatives fail to account for migrant workers, who are vulnerable on two fronts. First, by virtue of being migrants, they often lose out on their entitlements at the destination, and second, their low position in the hierarchy of the industry makes them vulnerable to poor wages, lack of bargaining power, gender discrimination, weak legal positions, and so on. Indian emigrant workers who migrate to countries such as Taiwan, Thailand, Jordan, and Egypt to work in the textile sector face similar issues in their destination countries.

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights highlight the duty of the state to protect workers against rights abuses, and the responsibility of companies to respect human rights. But there is a lack of concrete local, social, and political governance. This, paired with growing concern by civil society and consumers about human rights violations, has led global brands and manufacturers to choose to comply with voluntary international labour standards such as the (SA 8000), 2014 and Fairtrade International Textile standards, 2016.

But can a Western multinational’s drive to institutionalise CSR practices change the ground reality? Is the naming and shaming of brand-name clothing manufacturers overshadowing the blatant labour violations in smaller, domestic value chains? Further, when compliance to codes of conduct and labour standards are reached out of fear or become ‘checkbox’ exercises, they could even create new forms of inequality for workers. Research on the real impacts of codes of conduct in the garment industry in Tiruppur found that while there may be tangible outcomes on health, safety, or wages, there is a lack of understanding around workers’ basic rights and freedoms. For CSR or policy initiatives to truly find effect in India, it is critical to recognise migrant workers’ rights and freedoms.

- Circular migration or rural-urban migration is dominant amongst lower-income groups and in remote rural areas (particularly in drought prone areas without access to basic resources, livelihoods, and high population densities). As per National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), if the migrants intend to move again to the last usual place of residence, or to any other place, then that migration is treated as temporary migration.

—

Know more:

- Read Mezzadri and Srivastav’s paper explaining the complex relationship between the organised-unorganised manufacturing sectors and the labour hierarchy.

- Learn about how the Clean Clothes Campaign aims to improve the working conditions and empower workers in the global garment and sportwear industry.

Do more:

- Check out the migration data and knowledge portal, which brings together the latest knowledge, expertise, and research on migration in India.

- Reach out to the authors at communications@indiamigrationnow.org to learn about their work on migration and to be part of their goal to make migration a key part of India’s development agenda. You can also follow their work @nowmigration.